ALAN SIMPSON offers a few pointers on dealing with the ongoing, Trump-led destruction of the norms of a rules-based international order established post-WWII

IT WAS from their office near the British Museum at 98 Great Russell Street that 100 years ago the newly born branch of the Italian Fascist Party issued an invitation to a ball in the heart of London, the first such event in Britain.

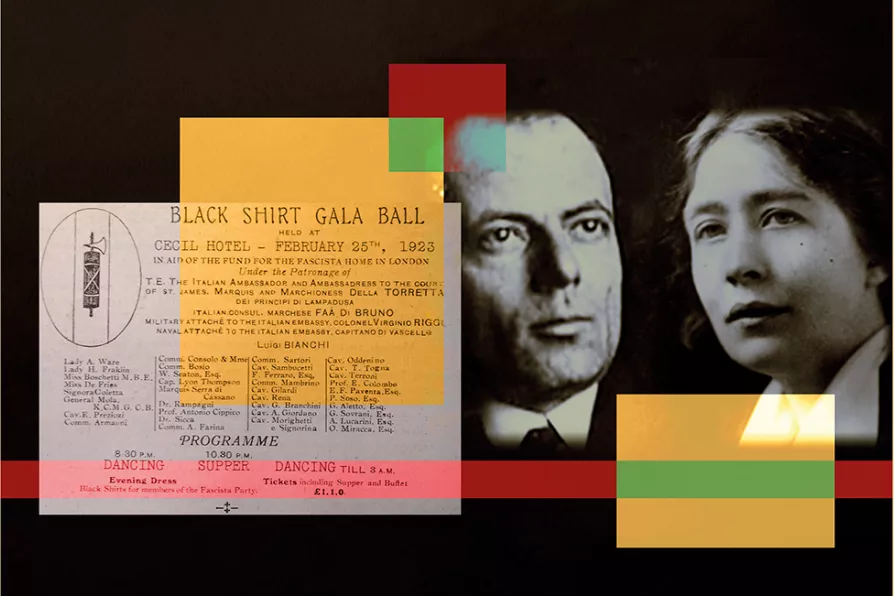

The “Black Shirt Gala Ball” was to be held at the luxurious Cecil Hotel in the Strand on February 25 1923 “in aid of the fund for the fascista home in London.”

The eyecatching announcement in the Italian fascist weekly L’Eco d’Italia listed: DANCING from 8.30 P.M. (Evening Dress, Black Shirts for members of the Fascista Party), SUPPER at 10.30 P.M. and more DANCING TILL 3 A.M.

CJ ATKINS commemorates one of the most dramatic moments in working-class history

Once again Tower Hamlets is being targeted by anti-Islam campaigners, this time a revamped and radicalised version of Ukip — the far-right event is now banned by the police, but we’ll be assembling this Saturday to make sure they stay away, says JAYDEE SEAFORTH

The annual commemoration of anti-fascist volunteers who fought fascism in Spain now includes a key contribution from Italian comrades