COMMUNISTS in Britain can be proud of their record of solidarity with the people of China in the latter’s struggle for unity, sovereignty and social justice.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Tom Mann and George Hardy visited China to assist in the unionisation of Chinese workers. The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB, today known as the CPB) organised protests against the Japanese invasion and occupation, with dockers and seafarers striking to halt the shipment of munitions to Japan.

The same British companies, such as Vickers and ICI, were also busy supplying Nazi Germany.

From the Hands Off China movement in the 1920s to the post-war Hands Off Korea campaign, Britain’s communists and their allies opposed British, Japanese and US military intervention in China and its neighbouring countries.

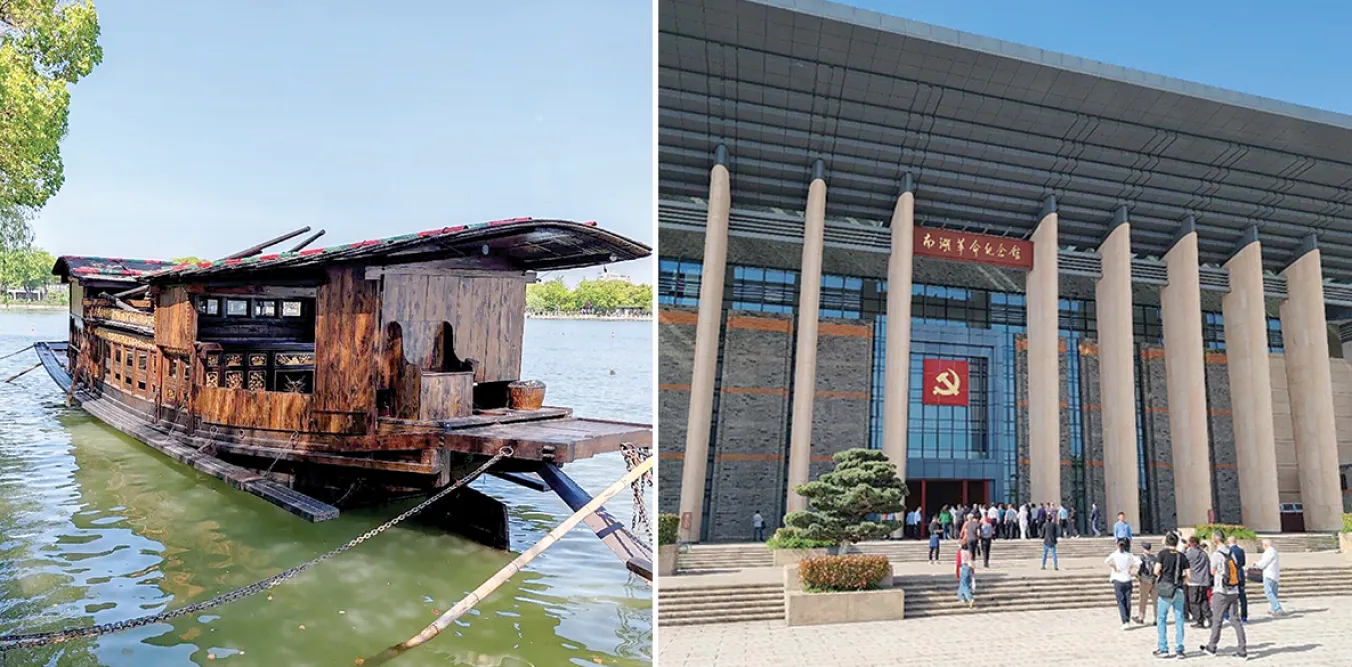

The proclamation of the People’s Republic of China on October 1 1949 marked the dawn of a new era for the Chinese people. As the CPGB’s new programme, Britain’s Road to Socialism, put it in 1951: “The Chinese revolution has freed hundreds of millions from the grip of the landlords and the foreign bankers.”

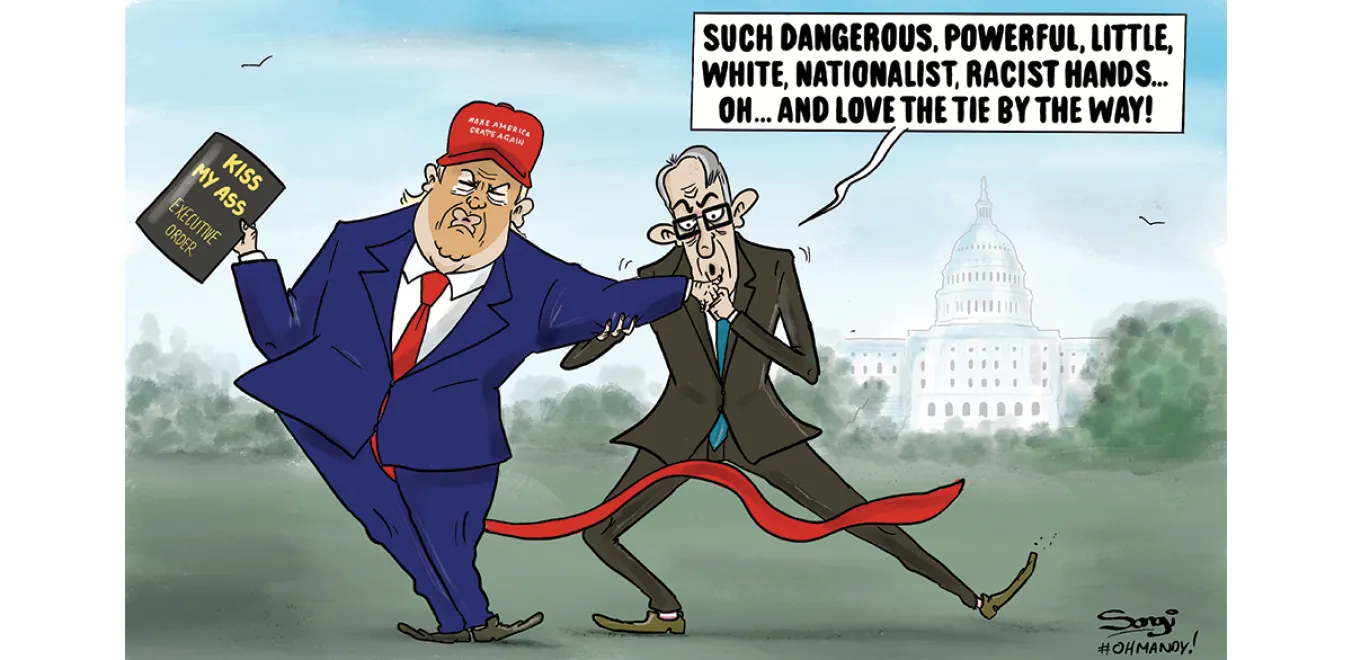

The party’s leadership also warned that US imperialism, now in the throes of cold war hysteria, would seek a pretext for going to war with China. Dismissed as far-fetched “anti-Americanism,” these fears were realised all too soon when US-UN armed forces advanced on China during the Korean War, drawing a devastating response from Chinese liberation army volunteers.

US president Truman and commander in chief General MacArthur threatened to unleash nuclear war, causing prime minister Clement Attlee to dash to Washington DC where he was assured in December 1950 that the US would not use “the bomb” without consulting Britain first — although Truman refused to put this in writing.

Arthur Clegg sounded a further warning against an atomic conflagration in a CPGB pamphlet the following year, No War With China.

At the same time, Britain’s communists were promoting constructive economic, social and cultural relations with the people of China.

Formed in 1949, the Britain-China Friendship Association (BCFA) attracted support from left and progressive trade unionists, co-operators, scientists, academics, artists, writers, musicians and business people.

No Labour Party organisations were among its 80 or so affiliated bodies, the BCFA having been put on Labour’s list of proscribed “communist front” organisations. Jim Mortimer, later to become Labour’s left-wing general secretary, 1982-85, was among those expelled from the party at the time for his support of the BCFA.

Undaunted, the association arranged a wide range of events showcasing China’s achievements, including mass literacy campaigns, the liberation of women from feudal shackles, extensive land reform and the first five-year economic plan (fulfilled with substantial Soviet assistance).

Daily Worker journalist Alan Winnington, whose reports of massacres by US forces and South Korean police cost him his British passport, later captured the drama and heroism of those early reforms in his classic book, Slaves of the Cool Mountains (1959).

Meanwhile, the BCFA continued to challenge British, US and Western economic, diplomatic and military aggression against People’s China head-on.

Against this background of unstinting solidarity, CPGB general secretary Harry Pollitt paid the first of three trips to China. Having championed Chinese freedom from Japan’s brutal occupation, he received a tumultuous welcome in spring 1955 in Beijing, Nanjing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Canton (Guangzhou) and Hangzhou.

In September 1956, along with Willie Gallacher and George Caborn, Pollitt attended the 8th Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC).