Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

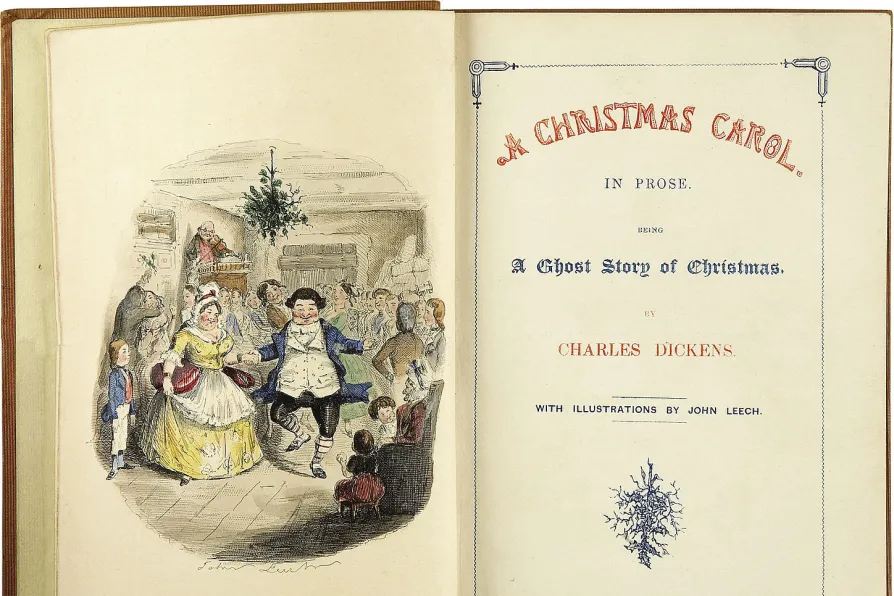

A TALE AGAINST THE RICH: Charles Dicken's most famous work in its first edition, 1843

A TALE AGAINST THE RICH: Charles Dicken's most famous work in its first edition, 1843

CHARLES DICKENS wrote A Christmas Carol at remarkable speed, and it was published on December 19 1843. It had already sold 5,000 copies before Christmas Day that year — in a decade that was known as the Hungry Forties. The similarities with modern “foodbank Britain” are striking.

In Dickens’s book, Ebenezer Scrooge runs a financial business off Cornhill in the heart of the City of London, and the author takes us to his counting house on Christmas Eve.

Scrooge is in one office and across the way is his clerk Bob Cratchit. The office is barely heated, Scrooge being frugal in most things.

The summer saw the co-founders of modern communism travelling from Ramsgate to Neuenahr to Scotland in search of good weather, good health and good newspapers in the reading rooms, writes KEITH FLETT