John Wojcik pays tribute to a black US activist who spent six decades at the forefront of struggles for voting rights, economic justice and peace – reshaping US politics and inspiring movements worldwide

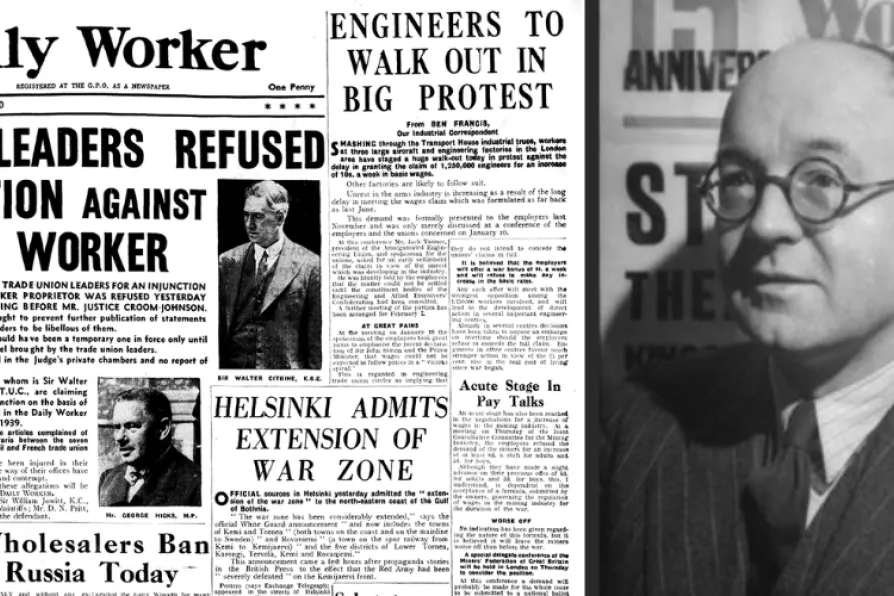

The last issue of the Daily Worker before it was banned (left), editor William Rust (right)

The last issue of the Daily Worker before it was banned (left), editor William Rust (right)

BANS on left media seems to be all the rage in eastern Europe. But there was a time when the main left newspaper in Britain faced a similar challenge.

The Daily Worker, forerunner of today’s Morning Star, played cat and mouse with censors, libel suits, grizzly judges — one was described in the paper as a “bewigged puppet” — and eventually, an outright ban, from its first day of publication, January 1 1930.

Indeed the appointment as “business manager” or editor of the paper, was once guaranteed a surefire spell in prison, usually Pentonville and considered part of the job description.

A chance find when clearing out our old office led us to renew a friendship across 5,000 miles and almost nine decades of history, explains ROGER McKENZIE

Communists lit the spark in the fight against Nazi German occupation, triggering organised sabotage and building bridges between political movements. Many paid with their lives, says Anders Hauch Fenger

PHIL KATZ looks at how the Daily Worker, the Morning Star's forerunner, covered the breathless last days of World War II 80 years ago

JOHN ELLISON recalls the momentous role of the French resistance during WWII