SWEE ANG, the founder of Medical Aid for Palestinians, is a big believer in the power of small actions, and she is the living proof it works, writes Linda Pentz Gunter

by Dr David Lowry, Institute for Resource and Security Studies

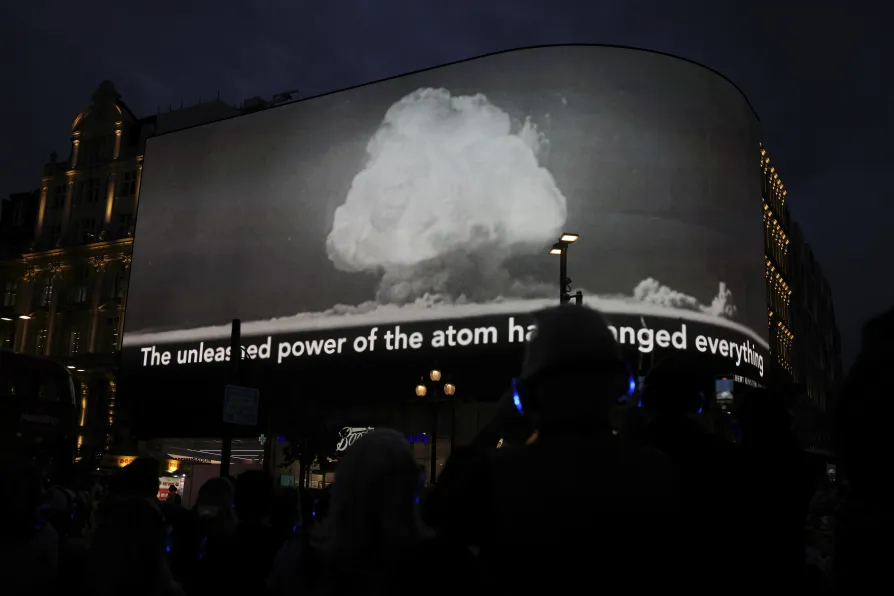

A digital art work by Es Devlin and Machiko Weston, is shown on the large LED screens at Piccadilly Circus in London, August 6, 2025, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the WWII U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan

A digital art work by Es Devlin and Machiko Weston, is shown on the large LED screens at Piccadilly Circus in London, August 6, 2025, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the WWII U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan

“FOR more than 60 years, good management and good fortune have meant that nuclear arsenals have not been used. But we cannot rely on history just to repeat itself, “ so said Margaret Beckett when Labour’s foreign secretary in a notable speech to a nuclear affairs conference in Washington DC on June 25 2007.

This week, as the world commemorates the atomic immolation of two Japanese cities — the unforgettable Hiroshima and Nagasaki — in which some 200,000 human beings were instantly incinerated and fatally irradiated, the nuclear sabres have been rattling once more.

President Trump theatrically pronounced he had “repositioned” two US nuclear submarines (he did not clarify whether they were nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed) in response to some bellicose nuclear rhetoric by ex-Russian President Dmitri Medvedev.

The latter was responding to the recent forward deployment by the US air force of new nuclear-armed fighter bombers at the RAF Lakenheath airbase in Suffolk, home of the US Strategic Air Command in Europe.

In the latest atomic tit-for-tat, the Kremlin announced on August 5 it was forward deploying intermediate range nuclear weapons to its ally Belarus and to the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, the furthest western Russian outpost. This is a blatant breach of the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

The Labour government is determined to fully back nuclear weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) for UK national defence. Starmer and Defence Secretary John Healey proclaim Trident and the new free-fall nuclear bombs to be deployed on F-35 jets as non-negotiable.

But all nuclear WMDs held by governments such as the UK’s are possessed in the mistaken belief that their possession adds to national security, rather than undermining it. This creates the conditions for almost certain accidents.

The most celebrated example of the deadly danger of so-called nuclear deterrence may be found in the Daily Telegraph obituary of September 18 2017 of Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, who has been dubbed “the man who saved the world.”

“Stanislav Petrov, a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Air Defence Forces, was the officer on duty at the Soviet Union’s early warning centre when malfunctioning computers signalled the United States had launched missiles at the country in September 1983.

“His decision to ignore warnings is credited with averting Atomic Armageddon. On the night of September 26, 1983, he was on duty at the Soviet Union’s early warning centre near Moscow when computers warned that the United States had fired five nuclear missiles at the country. The 1983 false alarm is perhaps the closest the world has come to nuclear war.”

The machine indicated the information was of the highest certainty,” Petrov later recalled. “On the wall big red letters burnt the word: START. That meant the missile had definitely been fired.”

He had just minutes to decide whether to assess the attack as genuine and inform the Kremlin that the United States was starting World War III — or tell his commanders that the Soviet Union’s early warning system was faulty. Guessing that a genuine US attack would have involved hundreds of missiles, he put the alarm down to a computer malfunction.

Lt Col Petrov was vindicated when an internal investigation following the incident concluded that Soviet satellites had mistaken sunlight reflected on clouds for rocket engines. The Soviet government’s policy in the event of a US nuclear attack was to launch an immediate and all-out retaliatory strike in accordance with the principle of Mutually Assured Destruction.

Although Petrov was feted by his colleagues and initially praised by superiors for his actions, he was not rewarded.He later complained that he was scolded by superiors for failing to complete a routine paperwork during the incident and had been scapegoated by generals embarrassed by the failure of the early warning system.

A premier of a Danish documentary film, The Man Who Saved The World, that recounted these events was screened at an international nuclear disarmament conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons organised by the Austrian foreign ministry in December 2014, which I attended along with several US nuclear weapons experts. It was a chilling experience for each of us.

A very detailed survey of other such incidents — called “Broken Arrows” in the understated language of nuclear weapons risk experts — are contained in a terrifying report published by the distinguished international affairs London think tank, Chatham House in April 2014, under the title: Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy, by Dr Patricia Lewis, then the research director for international security, and her colleagues Dr Heather Williams, Sasan Aghlani, and Benoit Pelopidas.

An equally disturbing study is the new book Nuclear War: a scenario, written by Los Angeles-based author Annie Jacobsen, who in 344 pages takes the reader step by step through how a geopolitical crisis can lead to the catastrophic exchange of nuclear weapons. Based on dozens of interviews with high-level nuclear WMD decision-makers, she constructs an all too real escalatory scenario that involves, inter alia, the atomic destruction of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in southern California.

Just last week reports reached me from an eyewitness contact in the former closed small city of Sosnovy Bor (“Pine Wood)” that three swarms of Ukrainian drones had attacked the giant nuclear complex next to the city. The Sosnovy Bor atomic complex contains six nuclear plants, a reprocessing facility, plutonium and radioactive waste stores and next door is an atomic powered rocket research centre.

The plant is on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, around 70 miles west from St Petersburg, in the Leningrad oblast (region).

The drones damaged the high voltage power lines that feed into the nuclear complex. This power is needed constantly to keep cool the radioactive waste in giant cooling tanks. If the cooling is halted, it could lead to the waste overheating and an explosion.

This is exactly what happened at a different nuclear waste complex at Kyshtym, in Chelyabinsk oblast, in early October 1957. A waste tank exploded, contaminating the local Techa River, and the surrounding forest, which still remains closed off nearly 70 years later.

Ukrainian academic Sergio Plokhy, now based in the United States, published a 200-page study last year “Chernobyl Roulette: a War Story,” on the Russian drone attacks on the Chernobyl sarcophagus that covers the reactor stricken by the major 1986 accident. He concludes:

“What has been absent so far in the variety of international responses to Chernobyl 11 is any concentrated effort to rethink the international legal order and reform the International Atomic Energy Agency to make it capable of reacting in a timely and effective manner.”

The breaching of the nuclear faith

The continued blatant violation by the UK of its legal obligations to be engaged in good faith negotiations towards nuclear disarmament, as stipulated by Article 6 of the Non Proliferation Treaty (NPT), puts the UK on a much higher nuclear naughty step than other alleged violators, like Iran.

The UK is the worst violator because it is a depositary state (with the US and Russia, originally the USSR, who have entered into several nuclear arms control and disarmament negotiations in SALT 1 &2, START, and INF), charged with protecting the interests of signatory member states. China and France, as later nuclear weapon state signatories to the NPT, are also in violation, but do not have depositary state status.

Defence ministers like to make statements like: “We constantly have discussions right across government to make sure that our continuous at-sea nuclear deterrence can be sustained… and will continue to do so in the long term.. our nuclear deterrent has kept Britain, and also our Nato partners, safe over 50 years… We have to recognise the need to invest in a whole spectrum of different capabilities, [including] nuclear deterrence…”

This contemporary ministerial assertion in respect of the continuous requirement for British nuclear weapons could have been cited from defence ministers going back over 60-odd years.

Up to 1968 that was a national security decision, purely the responsibility of the government of the day. Post-1968 when the UK signed the NPT, the UK’s possession and deployment was no longer solely a UK national security issue, but an international legal nuclear disarmament obligation.

Using materials extracted from British official diplomatic papers which I discovered in the British National Archives, it is possible to demonstrate the differences between British official disarmament promises recorded for posterity and contrast those with the subsequent belligerent nuclear practice of development and deployment of Polaris and its replacement Trident nuclear WMD systems, in violation of clear NPT commitments and on-the-record pledges.

A memorandum prepared by the Foreign Office in advance of the visit to London of the then Soviet premier, Alexei Kosygin, in February 1967, included the following final paragraph:

“We assume that the Soviet Union regard, as we do, the proposed review conference (for the NPT) as being an adequate assurance to the non-nuclears that the military nuclear powers are serious about the need for action on nuclear disarmament.”

Nearly a year later, on January 18 1968, Fred Mulley MP, the then Labour minister of state for disarmament at the Foreign Office, told the 358th plenary meeting of the Eighteen Nation Disarmament Committee (ENDC) — the forerunner to the present day UN Committee on Disarmament (CD) — in respect of the then proposed Article 6 of the nascent NPT:

“My own government have consistently held that the [Nuclear Non-proliferation] Treaty should and must lead to such [nuclear] disarmament.”

He added: ”If it is fair to describe the danger of proliferation as an obstacle to disarmament, it is equally fair to say that without some progress in disarmament, the NPT will not last…. as I have made clear in previous speeches my government accepts the obligation to participate fully in the negotiations required by Article 6 and it is our desire that these negotiations should begin as soon as possible (emphasis added) and should produce speedy and successful results. There is no excuse now for allowing a long delay to follow the signing of this Treaty, as happened after the Partial Test Ban Treaty, before further measures can be agreed and implemented.”

Mr Mulley subsequently wrote a confidential memorandum to the British Cabinet Defence and Overseas Policy Committee (OPD(68)6), on January 26 1968, in which he set out the then policy position on NPT article 6 (which at this stage in negotiations did not yet include the clause “at an early date”:

“A number of countries may withhold their ratification of the treaty until the nuclear weapon states show they are taking seriously the obligations which this article imposes upon them. It will therefore be essential to follow the treaty up quickly with further nuclear disarmament measures if it is to be brought into force and remain in force thereafter.”

If we leap forward nearly 40 years, we can see what the then New Labour Foreign Office ministers thought about the status of British nuclear disarmament under the NPT.

On March 10 2007, the then Foreign Secretary had a Letter to the Editor published in The Times, under the headline Is Mr Gorbachev’s concern over Trident misplaced? responding to an earlier letter published on March 8, from former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev. Inter alia, she wrote: “[By replacing Trident we will] simply enable the UK to maintain a deterrent until we can achieve our continuing objective of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

She later added:

“…We continue to encourage Russia and the US to make further bilateral [nuclear disarmament] progress. They are still some way from the point at which the part of the global stockpile that belongs to the UK (less than 1 per cent) would need to be included in such negotiations.”

A few weeks later in early May 2007 in Vienna, the then British disarmament ambassador, Foreign Office diplomat John Duncan, presented the UK submission to the NPT preparatory committee, asserting: “The United Kingdom is absolutely committed to the principles and practice of multilateral nuclear disarmament. Our ultimate goal remains unchanged: we will work towards a safer world free from nuclear weapons — and we stand by our unequivocal undertaking to accomplish their total elimination.”

He went on to claim that the UK “continues to support the disarmament obligations set out in Article 6 of the Treaty [NPT] and has an excellent record in meeting these commitments.”

This was, and remains, a contestable claim, as the Article 6 that the ambassador invoked requires the nuclear weapons states signed up to the NPT “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

Not one UK nuclear weapon or warhead had, or has since, been withdrawn from operational service as a result of multilateral disarmament negotiations in the 55 years of the NPT, as was confirmed for example in a written reply by the then defence secretary Des Browne MP, who told the independent MP Dai Davies in a written reply: “None of the [nuclear weapons reductions since 1998] have taken place as a result of any separate multilateral disarmament negotiations.”

And then, as now, nearly 17 years on, none of Britain’s nuclear arsenal features in any nuclear disarmament negotiations. The only UK nuclear weapons withdrawn from service over the past five decades are those declared surplus to requirements by the military, by unilateral decision by government, so they represent no reduction in nuclear reliance.

The UK has presented a genuinely schizophrenic policy on need for retention of nuclear WMDs and aspiration towards a nuclear weapons-free world for the entire 60-year period since the NPT was signed on July 5 1968, with justification for possession and deployment of nuclear WMDs coming alongside pledges for nuclear disarmament, but never quite yet.

On June 25 2007, Margaret Beckett MP made that valedictory speech as British foreign Secretary at the annual Carnegie Endowment Non-Proliferation conference in Washington DC, with which I started. She told delegates robustly in her keynote speech:

“What we need is both vision — a scenario for a world free of nuclear weapons. And action — progressive steps to reduce warhead numbers and to limit the role of nuclear weapons in security policy. These two strands are separate but they are mutually reinforcing. Both are necessary, both at the moment too weak… weak action on disarmament, weak consensus on proliferation are in none of our interests… we need the international community to be foursquare and united behind the global non-proliferation regime…. so we have grounds for optimism; but none for complacency.

“The successes we have had in the past have not come about by accident but by applied effort. We will need much more of the same in the months and years to come. That will mean continued momentum and consensus on non-proliferation, certainly. But, and this is my main argument today, the chances of achieving that are greatly increased if we can also point to genuine commitment and concrete action on nuclear disarmament… after all, we all signed up to the goal of the eventual abolition of nuclear weapons back in 1968; so what does simply restating that goal achieve today? More than you might imagine. Because, and I’ll be blunt, there are some who are in danger of losing faith in the possibility of ever reaching that goal.

“When it comes to building this new impetus for global nuclear disarmament, I want the UK to be at the forefront of both the thinking and the practical work. To be, as it were, a “disarmament laboratory.”

Following the bombing of Iran in June, are there any prospects for a Middle East WMD free zone?

Israel is the only nation in the region possessing nuclear weapons, and which consistently refuses to join the NPT.

However, at the completely overlooked Paris Summit of Mediterranean countries, held on July 13 2008, under the co-presidency of the French Republic and the Arab Republic of Egypt and in the presence of Israel — which was represented by its then prime minister, Ehud Olmert — the issue of peace within the region were explored in depth, and the final declaration stated the participants were in favour of “regional security by acting in favour of nuclear, chemical and biological non-proliferation through adherence to and compliance with a combination of international and regional nonproliferation regimes and arms control and disarmament agreements.”

The final document goes on to say:

“The parties shall pursue a mutually and effectively verifiable Middle East Zone free of weapons of mass destruction, nuclear, chemical and biological, and their delivery systems. Furthermore the parties will consider practical steps to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons as well as excessive accumulation of conventional arms; refrain from developing military capacity beyond their legitimate defence requirements, at the same time reaffirming their resolve to achieve the same degree of security and mutual confidence with the lowest possible levels of troops and weaponry and adherence to CCW (the convention on certain conventional weapons) promote conditions likely to develop good-neighbourly relations among themselves and support processes aimed at stability, security.”

Despite all that has happened in Gaza, the bombing of Iran, Lebanon, Yemen and Syria by Israel in the past few months, there is hope that a secure peace without nuclear weapons can be achieved in the globe’s most volatile region.

What would nuclear disarmament mean?

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

Yet the US has currently deployed worldwide 9,938 nuclear weapons, according to an excellent study, Model Nuclear Inventory, prepared by a New York-based non-governmental organisation, Reaching Critical Will.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

The “Nuclear Ban” Treaty, whose originators and promoters — the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) — were awarded the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for their initiative and its success, is an essential complement to the NPT regime.

A report (also by Reaching Critical Will, an international disarmament and diplomatic lobby group based in New York) on the conference hosted by the Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Vienna in December 2014 — which I attended — shows how it created the diplomatic climate for the Ban Treaty to be actualised. It is titled: Filling the gap: report on the Vienna conference on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons: a conference report for the meeting hosted by the government of Austria on December 8-9 2014 on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons. It is compelling reading. I provided a detailed written submission to the Vienna conference on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons.