As the RMT Health and Safety Conference takes place, the union is calling for urgent action on crisis of work-related stress, understaffing and the growing threat of workplace assaults. RMT leader EDDIE DEMPSEY explains

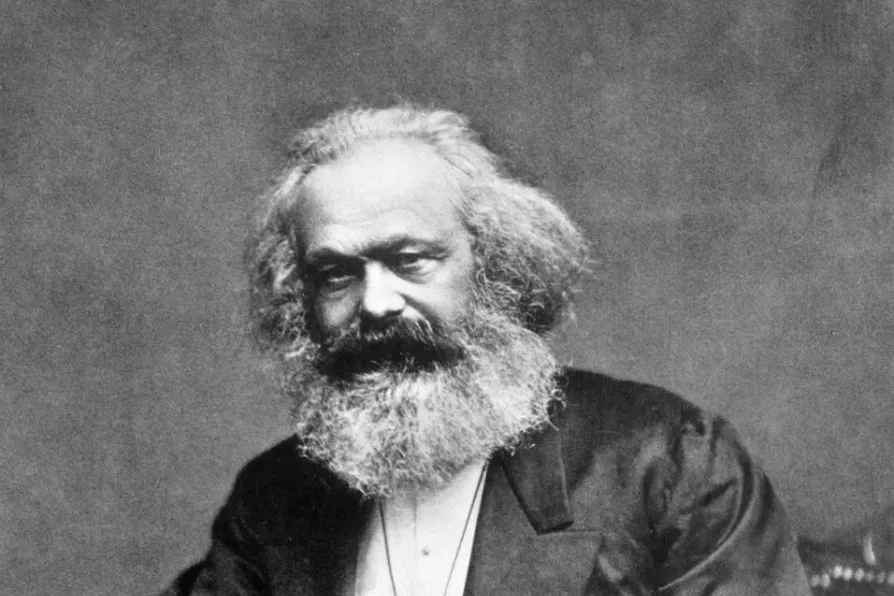

Marx doesn’t have to be ‘difficult’

SOLOMON HUGHES recommends a short and sharp introduction to Marxism

KARL MARX wanted to do two things at once: he wanted to understand how change happened in a complex, shifting world.

He also wanted to give working people the tools to change things for themselves.

The first meant he used an array of complicated theoretical analyses and was willing to turn existing understandings of society on their head or inside out.

Similar stories

The summer saw the co-founders of modern communism travelling from Ramsgate to Neuenahr to Scotland in search of good weather, good health and good newspapers in the reading rooms, writes KEITH FLETT

From bemoaning London’s ‘cockneys’ invading seaside towns to negotiating holiday rents, the founders of scientific socialism maintained a wry detachment from Victorian Easter customs while using the break for health and politics, writes KEITH FLETT

Author RACHEL HOLMES invites readers to come to her talk in London about the great foremother of the working-class women’s movement – Eleanor Marx