By pressuring Mexico to halt oil shipments, Washington is escalating its blockade of Cuba into a direct bid for economic collapse and regime change, argues SEVIM DAGDELEN

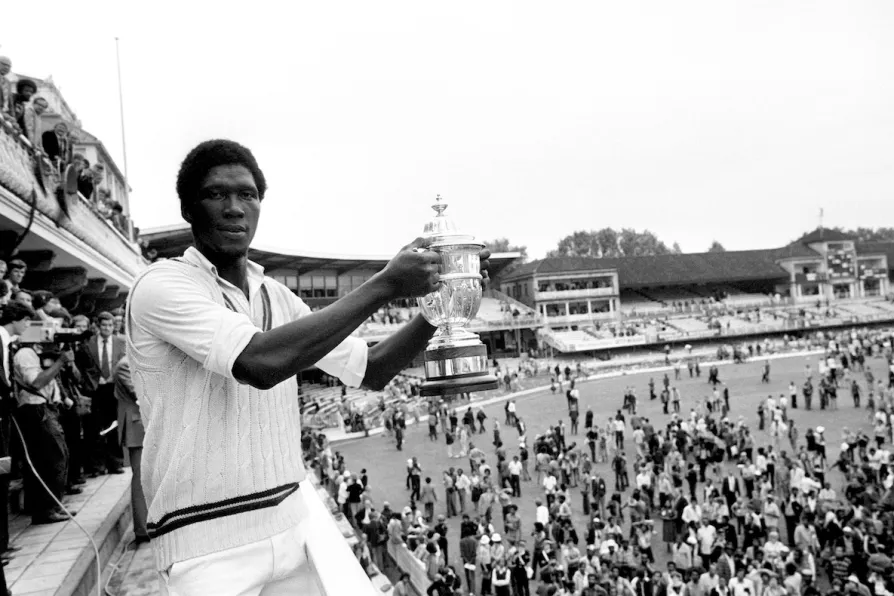

SOURCE OF PRIDE: Joel Garner holds aloft the World Cup trophy for the West Indies at Lords, June 1979

SOURCE OF PRIDE: Joel Garner holds aloft the World Cup trophy for the West Indies at Lords, June 1979

IT’S April and the weather is mostly awful — so it must be the start of the cricket season.

When I was growing up, I had just two small ambitions for my future. One was to play football for Aston Villa in the winter, and the other was to come in at first or second wicket down for the West Indies cricket team in the summer.

Sadly I was never good enough at either to succeed, although at times over the years, I still felt I could do a job for Villa given some of the rubbish being served up — thankfully now, under Unai Emery, things appear to have turned the corner.

Morning Star international editor ROGER McKENZIE reminisces on how he became an Aston Villa fan, and writes about the evolution of the historic club over the years

RAHMAN OSMAN speaks to fan favourite Aston Villa forward Ollie Watkins about bringing his childhood dream to life on the pitch