RAMZY BAROUD sees Gaza abandoned while the genocide continues

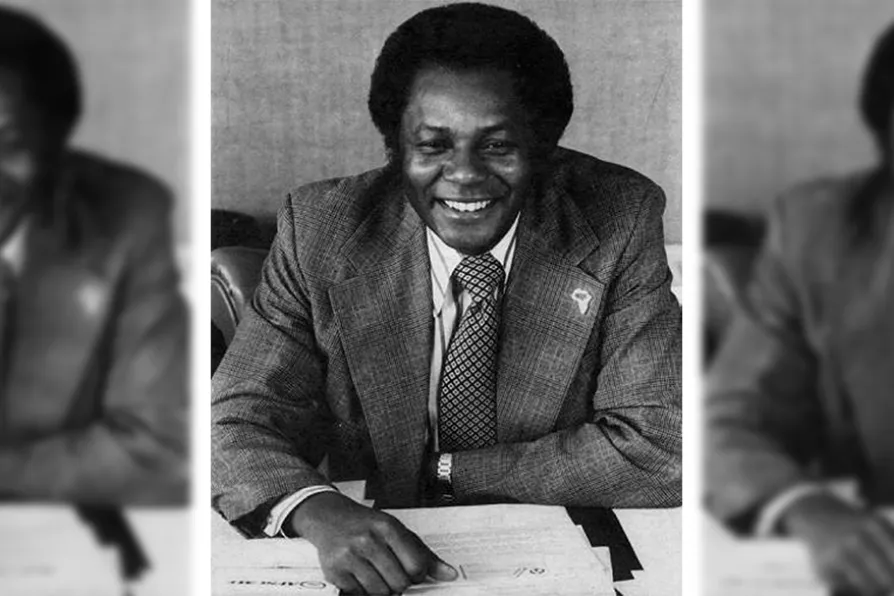

Bill Lucy

Bill Lucy

I WANT to celebrate the life and influence of arguably the most important trade unionist of African descent in history.

William “Bill” Lucy joined the ancestors last week aged 90 and was, if an ancestral realm exists, afforded a hero’s welcome.

Lucy transitioned at his home in Washington DC after around 60 years of organising, influencing and making things happen for black and white people in his homeland of the US but also internationally.

It would be a mistake to think that just because Lucy was known as a black trade union leader that he didn’t also make a difference for white workers.

You don’t work as the secretary-treasurer (the number two) of one of the largest trade unions in the US — the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees — by only concentrating on what happens to black workers. You do it by understanding the importance of empowering black workers but also the power of black-and-white unity.

But many reading this will never have heard of this person that I have described in such glowing terms. However, many will at least have heard of the strike of Memphis sanitation workers in 1968. Dr Martin Luther King was in Memphis to support this historic strike when he was assassinated on April 4 of that year.

The deaths of Ecole Cole and Robert Walker, who fell into the back of a refuse-collecting vehicle and the otherwise disgusting treatment of the workers, was the spark that lit the fuse for the strike.

Lucy was instrumental in popularising the signs that became synonymous with the strike: “I Am a Man,” which underpinned the demand for dignity and respect that lay at the heart of the strike of 1,300 African-American sanitation workers.

In 1969, Lucy became an assistant to Jerry Wurf, the president of the predominantly white AFSCME.

Three years later, he was elected as the number two in the union — secretary-treasurer — a position he held for 38 years until he retired in 2010.

In 1972, angered by the position taken by the US union federation, the AFL-CIO, to remain neutral in the presidential contest between the corrupt and anti-union Richard Nixon and George McGovern, Lucy became one of the founding members of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists.

Lucy was elected the first president of the CBTU and served in that role until 2013.

But Lucy always understood that for black workers, racism does not begin and end at the workplace.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Lucy was one of the foremost campaigners against the racist apartheid regime in South Africa. He was one of the leaders of the influential TransAfrica Forum that co-ordinated many of the anti-apartheid economic boycott campaigns within the US.

He was one of the first to welcome Nelson Mandela to the US in 1990, soon after the great leader had been released by the racist regime.

In 1994, he became the first black president of Public Services International, which represents millions of public service workers across the globe.

I first met Lucy in 2001 in the Canadian capital, Ottawa, as trade unionists from across the globe came together to organise our presence for the UN World Conference Against Racism to be held later that year in Durban, South Africa.

As someone who has long prided themselves on knowing my black progressive history, I was ashamed that I was simply unaware of the things I have just told you about Lucy.

Neither did he tell me about any of this in the way I am pretty sure many trade union leaders I have met over the years would not have hesitated to do. I went away and found out for myself who this wonderful man really was.

Lucy was one of the most humble and nicest people that I have ever met — admittedly, not a high bar to meet in some parts of the trade union movement.

For him to take, as I was then, a pretty junior TUC race equality officer under his wing at that meeting in Ottawa and for us to become instant friends was something incredibly special.

We next saw each other in Durban at the UN conference, and it was like meeting my father again after an extended break. I sat with him on many occasions during that extremely fraught conference and just talked and listened. I felt that I was in the presence of someone really special.

He soon became my mentor, confidant and, much more than a friend, I regarded him as family.

I think it was the following year that Lucy was the fraternal speaker from the AFL-CIO to the TUC Congress. I remember getting messages saying Lucy was asking for me. When I tracked him down, he was speaking with a very senior British trade unionist. Lucy politely cut the discussion short and gave me the biggest hug possible.

There were some incredulous looks of astonishment, wondering how this junior member of staff could be afforded such a hello.

I remember some years later, Lucy invited me to be a guest speaker at the CBTU Convention in Atlanta, Georgia. My mum was still around at the time, and I had told her lots about Lucy and what an important influence on me he had become. She insisted that I dress properly and wear a suit and tie to speak with proper respect for Lucy.

I actually didn’t need telling, but this said more about the respect that Lucy was viewed by Mum, who never met him. It’s likely the last time I wore a suit.

Some years later, I had the honour of being invited to stay with Lucy at his Washington DC home when the CBTU Convention took place in the US capital.

I was invited again earlier this year, but because of ridiculous logistical problems, it never happened.

Later, as a senior black trade union official, I didn’t have too many people I could share my trials and tribulations with without fear that they would go running to the people who were the cause of the problems.

I remember many transatlantic calls between us where Lucy never presumed to give advice or even tell me of what must have been the many difficult circumstances he had to face over the years. Instead, he just listened and asked questions and guided me towards ways of being able to cope with some pretty horrible situations.

Often, when I was in a state, my wife Kate would say: “Call Bill.” She knew that I would always leave those calls picked up off the floor.

One thing that I took from my friendship with Lucy is that I don’t have to share the exact same politics with someone to respect them or to be close friends. Lucy was a staunch supporter of the Democratic Party in the US, and I am decidedly not a supporter of that kind of politics.

But I still learned from Lucy, and he told me once that he had learned from me — although I think this was rather about what not to do.

I already miss my friend. He was a special man who I will always remember and try to be a fraction of the human being that he was.

Thank you for your friendship, Bill Lucy. You are an everlasting star enriching the ancestors.

‘Chance encounters are what keep us going,’ says novelist Haruki Murakami. In Amy, a chance encounter gives fresh perspective to memories of angst, hedonism and a charismatic teenage rebel.