Labour prospects in May elections may be irrevocably damaged by Birmingham Council’s costly refusal to settle the year-long dispute, warns STEVE WRIGHT

From Engels to Boris Johnson: the return of ‘social murder’

The PM’s inaction over Covid has parallels with politicians of mid-19th-century England, writes KEITH FLETT

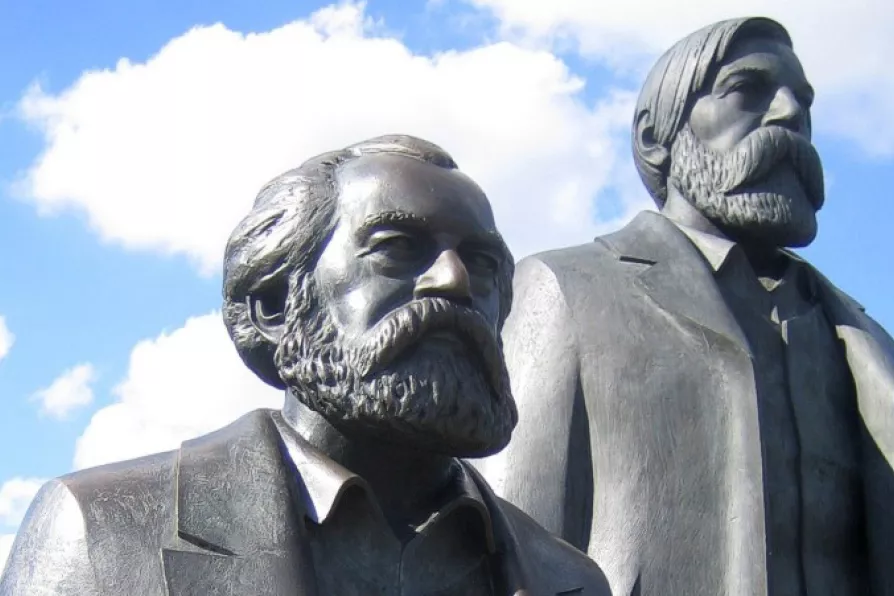

Engels (right) with Marx, statue in Berlin

[Manfred Bruckels/cc]

Engels (right) with Marx, statue in Berlin

[Manfred Bruckels/cc]

FRIEDRICH ENGELS’s book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, is a well-known classic of social history.

His investigations helped to inform the important understandings of Karl Marx and himself about how capitalism does and does not work.

One concept that he mentions in the book has recently begun to receive attention again.

Similar stories

The summer saw the co-founders of modern communism travelling from Ramsgate to Neuenahr to Scotland in search of good weather, good health and good newspapers in the reading rooms, writes KEITH FLETT

From bemoaning London’s ‘cockneys’ invading seaside towns to negotiating holiday rents, the founders of scientific socialism maintained a wry detachment from Victorian Easter customs while using the break for health and politics, writes KEITH FLETT

Starmer’s slash-and-burn approach to disability benefits represents a fundamental break with Labour’s founding mission to challenge the idle rich rather than punish the vulnerable poor, argues KEITH FLETT

The legacy of an 1820 conspiracy in revenge for Peterloo resonates down the ages, argues KEITH FLETT