“NEVER can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping floundering condition which is this High Court of Chancery,” wrote Charles Dickens in Bleak House.

Famously he used the smog of London as a metaphor for the all enveloping bureaucracy and obfuscation which engulfed the case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce that lies at the heart of the novel.

Such was the outrage at Dickens’ depiction of the courts that Bleak House played its role in the reform of the legal system in the 19th century.

And yet here we are. In the 21st century with an innocent journalist currently enduring his fourth year in Belmarsh high-security prison. The Victorian smog has gone, but the stench of justice delayed still hangs heavy in the air.

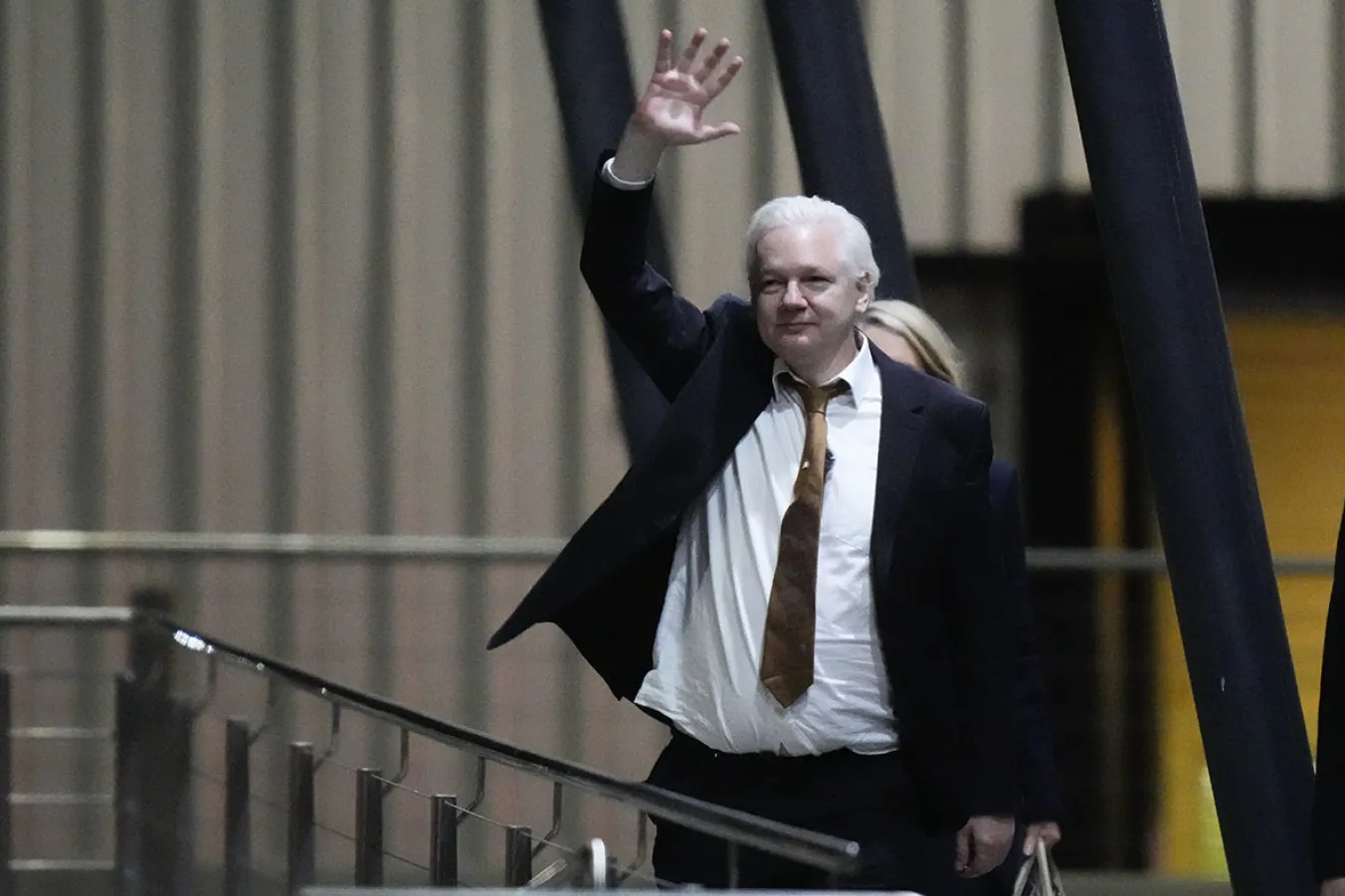

Julian Assange’s prospects would be grim indeed if he were reliant only on the painfully slow processes of the High Court, currently months into its deliberation about whether it will even hear his latest appeal against extradition to the US where he would be tried under Espionage Act charges and possibly face a 175-year prison sentence.

But fortunately he is not. His case relies not just on the High Court, but on the Court of Public Opinion, as all high-profile political cases do. And in this court, opinion is swinging ever more powerfully in Assange’s direction.

In the last six months there have been some dramatic developments. Last October the Human Chain for Assange that surrounded Parliament was the largest demonstration so far in Britain against his extradition.

Then all the newspaper titles that printed the stories for which he is being extradited, the Guardian, the New York Times, El Pais, Der Spiegel and Le Monde, issued a joint declaration calling for Assange’s release.

Then the Australian prime minister ended his low-key approach to lobbying on Assange’s behalf and made a public call for him to be released.

Most recently a tour of South America by WikiLeaks editor in chief Kristinn Hrafnsson and WikiLeaks ambassador Joseph Farrell was greeted by five presidents from Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia and Argentina, all of whom made statements calling for Assange’s release.

All this comes on top of the now widely accepted fact that many journalists’ unions, press freedom organisations and human rights groups across the globe have adopted Assange’s case as a litmus test of the state of the freedom of the press.

This is rapidly turning into, and being seen to turn into, a battle of the 99 per cent against the 1 per cent. The rest of us versus a tiny, entrenched, political-security-legal elite bent on the public punishment of a journalist who did what all journalists should aspire to do: let the public know vital information which governments and corporations are hiding from them.

The latest expression of support for Assange is the Night Carnival protest in London this Saturday, assembling at 4pm in Lincoln’s Inn Field, the very spot where Dickens pictured the poisonous fog to be thickest.

Its slogan is “Light into Darkness,” using the age old subversive nature of carnival to shine light on this very dark corner of the political and legal system.