New releases from Van Morrison, Tyler Ballgame, and Dry Cleaning

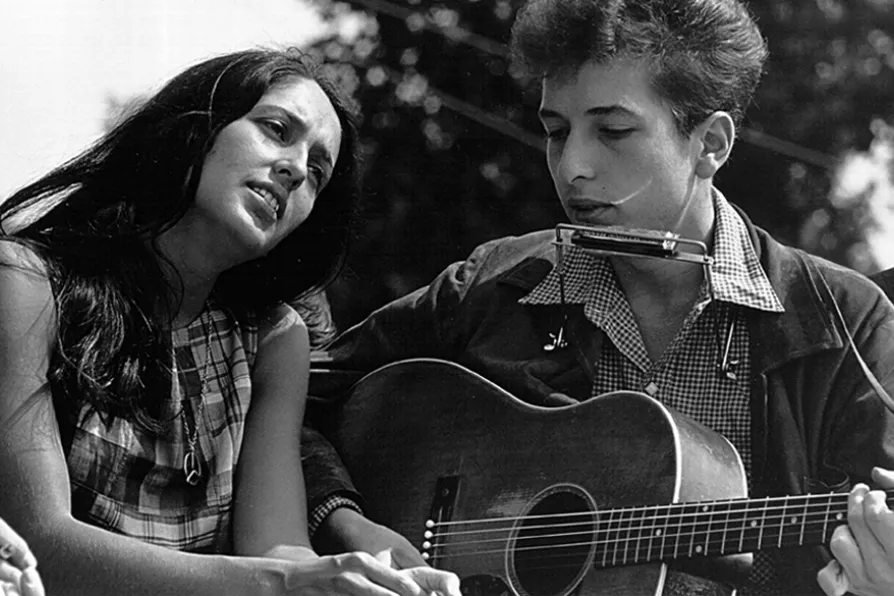

THE REAL THING: Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, Civil Rights March on Washington DC August 28 1963

[Rowland Scherman - National Archives and Records Administration/CC]

THE REAL THING: Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, Civil Rights March on Washington DC August 28 1963

[Rowland Scherman - National Archives and Records Administration/CC]

ON the last Sunday of this past October, a Timothee Chalamet look-alike contest broke out in Washington Square Park in New York City.

Chalamet made his way through the roiling sea of admirers and impersonators and let himself be photographed with the winner, Miles Mitchell. There is still no substitute for the presence of real people — for a star’s charisma and a worshipper’s scream and shudder.

Notwithstanding Washington Square’s status as a vital site of protest, it was strangely appropriate that this recent eruption of fandom took place there. The park is in Greenwich Village, the main location for the early 1960s rise to fame of the young Bob Dylan who is depicted in James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown. The Washington Square hijinks reveal that Mitchell-as-Chalamet looks more like Dylan than Chalamet-as-Dylan does.

TONY BURKE revels in the publication of previously unreleased tracks by the great US folksinger