TONY BURKE speaks to Gambian kora player SUNTOU SUSSO

GORDON PARSONS recommends a gripping account of flawed justice in the case of Pinochet and the Nazi fugitive Walther Rauff

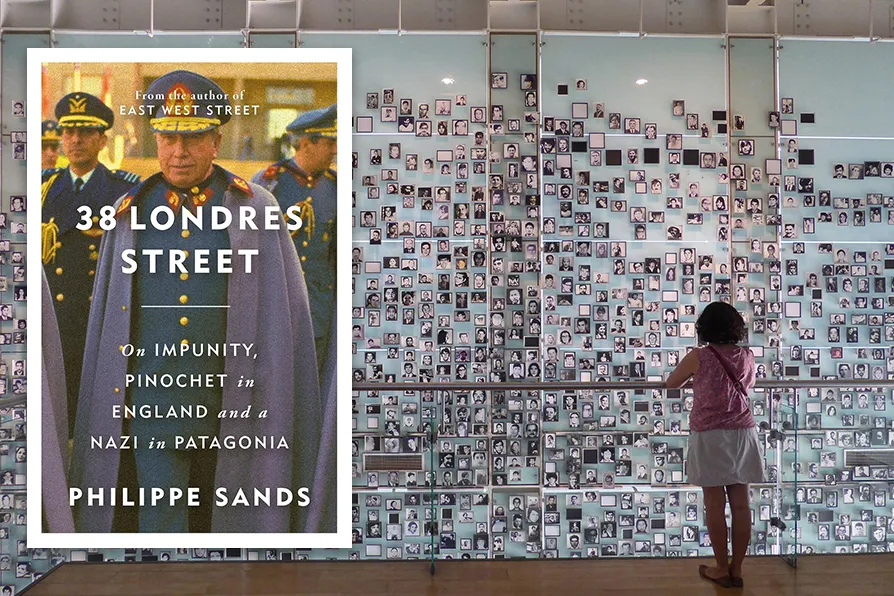

Portraits of victims in the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Santiago de Chile, 2017 [Pic: CARLOS TEIXIDOR CADENAS/CC]

Portraits of victims in the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Santiago de Chile, 2017 [Pic: CARLOS TEIXIDOR CADENAS/CC]

38 Londres Street

Philippe Sands, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25

THOSE who have read the international human rights lawyer Philippe Sands’s previous studies of the Nazi legacy in history — East West Street and The Ratline — and are inspired by his personal family connections and focus on uncovering the post-war lives of specific individual criminals will be delighted with this new book, recognising his remarkable, page-turning narrative skills.

For those unacquainted with these fascinating books, the title of what might be called the completion of a trilogy may not draw them in. The subtitle, however, “On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia,” makes clear its subject matter but not the gripping nature of the reading experience on offer.

Sands set out on a tortuous journey to untangle the linked lives of two multi-murderers: the better known, the notorious Augusto Pinochet, President of Chile from 1973 to 1990; and Walther Rauff, one of the leading SS Nazi officers who escaped like so many to South America.

Pinochet’s history from the 1973 CIA organised military coup, overthrowing Salvador Allende, Chile’s first socialist president, and his campaign of murder throughout his rule is well documented. “Within a year, the DINA [the junta’s equivalent of the Gestapo] was operating dozens of detention centres… around the entire country,” with Santiago’s 38 Londres Street being the address of his terror regime.

It was later estimated that under Pinochet’s leadership “40,000 people were legally attained or tortured, more than 3,000 murdered or disappeared [while] many put the numbers even higher.”

Rauff’s equally ruthless career involved climbing through the ranks of the SS as designer and organiser of prototype gas vans estimated to have killed 97,000 victims, and while being hunted after the war his varied activities included — amazingly — working for Mossad, the Israeli Secret Service, before fleeing to Ecuador.

Equally amazing was a spell spent travelling around South America recruiting for the West German Intelligence services before coming to rest as the manager of a crab-canning factory in Chile.

From this base he employed his Nazi skills to play a major part in Pinochet’s ruthless regime.

Throughout, Sands holds the reader’s attention on tenterhooks, alternating between seeking to uncover the real Rauff from the barrage of circumstantial information he meets, and the lead up to and account of Pinochet’s arrest on a visit to England and the struggle to have him extradited to Spain on charges including the savage assassination in 1976 of Carmelo Soria, a Spanish United Nations official.

The core of Sands’s work forensically covers the complex tensions of the legal battles through the British courts. This is the stuff of theatre and is crying out for adaptation as a television or stage documentary drama. While Sands recounts the unfolding court narrative he comments tellingly that “the experience of living through the same case and court but with different judges exploded the notion that the law is applied mechanically to the facts. Change the judges and everything changes. It’s the human factor.”

On one side, those anxious to bring to justice this monster included family members of the disappeared; those lawyers, British and Spanish, who were committed to human rights; Amnesty International; and Sands himself, who had originally been approached to argue for Pinochet in the High Court but had “chosen to support Human Rights Watch.” On the Pinochet side was the Chilean government with its fragile democracy in the midst of an election, the reluctant establishment of the Spanish government which had been outwitted by progressive Spanish lawyers and, Sands implies, Tony Blair’s British government who eventually were relieved to negotiate Pinochet’s return to Chile on questionable poor health grounds.

This, “the most significant international criminal case since Nuremberg,” was to decide the legality of holding leaders of countries accountable for their actions even when they are not in their home country — something particularly relevant to today!