PAUL FOLEY welcomes a dramatic account of the men and women involved in the pivotal moment of the 5th Pan African Congress

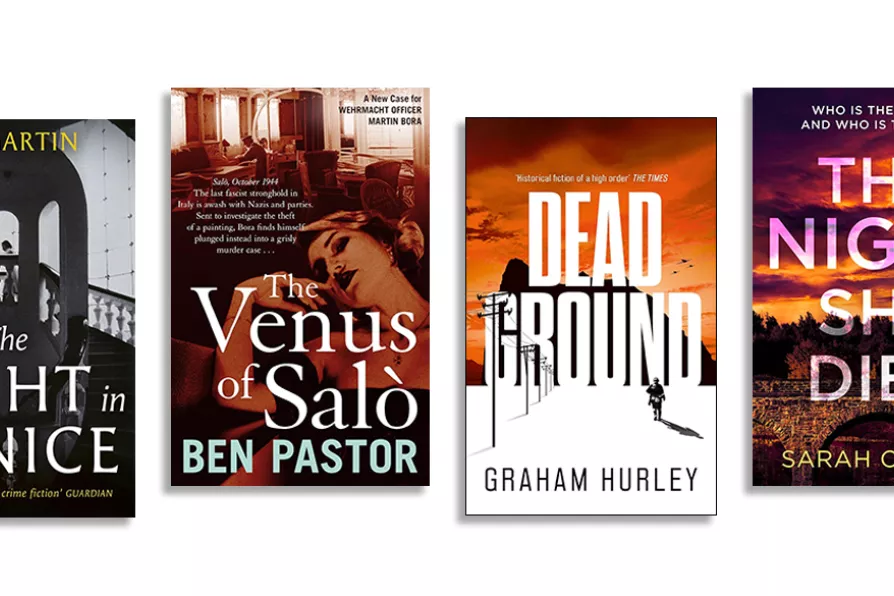

Fourteen-year-old Edwardian orphan Monica is, if not precisely respectable, at least from a respectable background, in The Night In Venice by AJ Martin (W&N, £22), even though life’s misfortunes have declassed her from Hampstead to the Holloway Road.

When her reluctant guardian, Driscoll, reluctantly takes her on holiday to Venice, her hopes of glamour and romance are smashed on the first morning when she awakes with a horrible feeling that she might have murdered Driscoll during the night.

Monica’s almost picaresque, slightly dreamlike adventures in Venice put me in mind of Raymond Queneau’s Zazie in the Metro, but the London scenes are more Patricia Highsmith, as we begin to realise this isn’t the first time the damaged child has had cause to worry that she’s done something irreversibly terrible. All in all, though, compelling, disturbing, and very funny, this curious novel is a genuine one-off.

Venus Of Salo by Ben Pastor (Bitter Lemon, £9.99), latest in an epic series mixing history with whodunnits, takes us to autumn 1944. Colonel Martin Bora of the Wehrmacht is summoned to Salo, the last redoubt of Italian fascism — at least until recently — in which the remnants of Mussolini’s doomed regime pretend to run the country under the all-but-explicit control of the Germans.

Bora is tasked with finding a missing Titian painting which Hermann Goring is eager to add to his collection. Distracted from his hunt by a series of murders and an unwise love affair, the melancholy maverick colonel soon has other things to worry about: the Gestapo believe they have at long last enough evidence to move against him.

Pastor never makes the error of presenting her protagonist as one of Hollywood’s “Good Germans.” He’s just an army officer, trying to do his duty without destroying his soul. The result is convincing historical fiction of a high order.

As indeed is Dead Ground by Graham Hurley (Head of Zeus, £20), set at the end of the Spanish Civil War. Annie, a French-British art enthusiast, was in Madrid as the revolt against democracy began, and volunteered as a Republican nurse. Being multilingual, however, means she has no chance of avoiding involvement in the intrigues of sundry spy agencies, while the Nazis plot to conquer Gibraltar and the British desperately try to keep Franco neutral.

People in Hurley’s world don’t always believe very passionately in their causes, but they always believe believably, and it’s that, as much as the meticulous historical research, which makes his thrillers so absorbing.

A troubled teenager is murdered in an Oxfordshire village in The Night She Dies by Sarah Clarke (HQ, £9.99), and some suspicious eyes fall on Lucy, a schoolmate who was being ruthlessly bullied by the dead girl. As if that wasn’t nightmare enough for Lucy’s mother, it quickly becomes obvious that more than one member of her family has a motive for the killing.

Likewise, the reader’s spotlight falls on one suspect after another, through several twists, until a denouement that is as eye-popping as it is logical.