RON JACOBS welcomes a timely history of the Anti Imperialist league of America, and the role that culture played in their politics

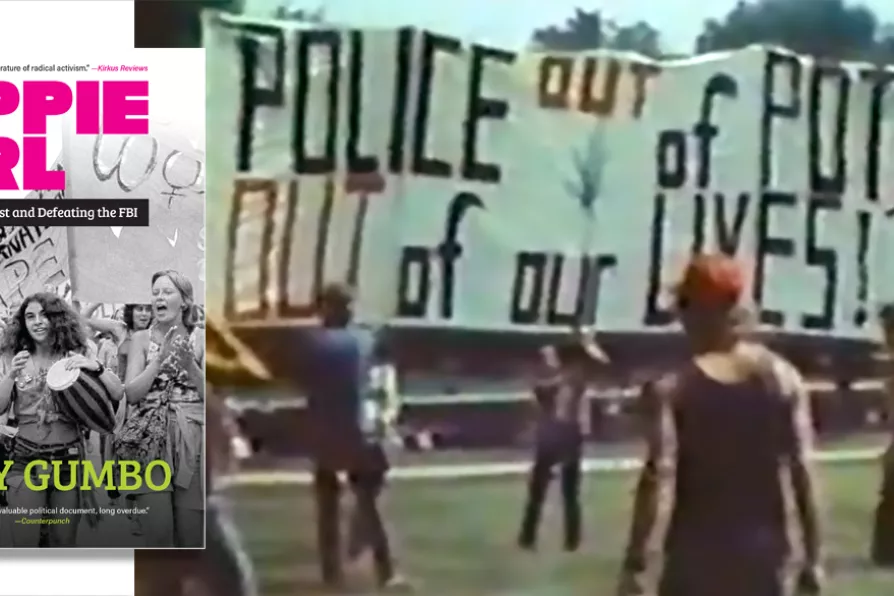

Yippie banner displayed at Washington DC Smoke-In on July 4 1977

[PumpkinButter/CC]

Yippie banner displayed at Washington DC Smoke-In on July 4 1977

[PumpkinButter/CC]

Yippie Girl: Exploits in Protest and Defeating the FBI

by Judy Gumbo

Three Rooms Press £11.99

IN THE male-dominated world of Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Stew Albert, Bill Ayers, Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver and the Berrigan brothers, women like Judy Gumbo, Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis and Bernardine Dohrn were personalities whose commitment was worthy of imitation.

The inspiration they provided went with me — as a high school pupil for US military dependents in Frankfurt am Main, Germany — to the anti-war protests I attended organised by German leftists and pacifists to coincide with the 1971 May Day actions against the war in Washington, DC and elsewhere around the US.

Gumbo’s is a joy to read. It is also an important and significant addition to the history of what is now known as the sixties. Part memoir and part confessional, it is mostly a history of the period told by one of its primary participants and instigators.

RON JACOBS welcomes a survey of US punk in the era of Reagan, and sees the necessity for some of the same today

RON JACOBS salutes a magnificent narrative that demonstrates how the war replaced European colonialism with US imperialism and Soviet power

RON JACOBS welcomes an investigation of the murders of US leftist activists that tells the story of a solidarity movement in Chile

RON JACOBS welcomes the translation into English of an angry cry from the place they call the periphery