GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

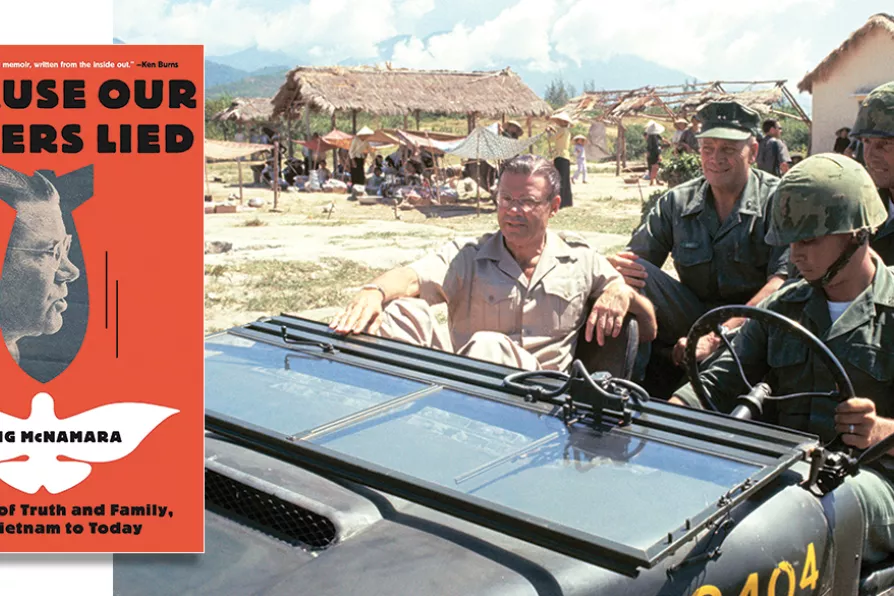

(L to R) Robert McNamara, Lt Col David Clement and Maj Gen Lewis and W Walt en route to the Le My City Hall during McNamara's visit to the Marine units in the area on July 18 1965

[manhhai/flickr/CC]

(L to R) Robert McNamara, Lt Col David Clement and Maj Gen Lewis and W Walt en route to the Le My City Hall during McNamara's visit to the Marine units in the area on July 18 1965

[manhhai/flickr/CC]

Because Our Fathers Lied: A Memoir of Truth and Family, from Vietnam to Today

by Craig McNamara

Little Brown and Company, £24.44

WHEN I read this book by the son of Robert McNamara, a key architect of the US war on Vietnam, I couldn’t help but compare my experience as the oldest son of an air force officer.

My dad wasn’t an architect of the US war on Vietnam; his role was that of an engineer.

Like thousands of others in the military and throughout the US bureaucracy of war, our fathers were family men.

RON JACOBS welcomes a survey of US punk in the era of Reagan, and sees the necessity for some of the same today

RON JACOBS salutes a magnificent narrative that demonstrates how the war replaced European colonialism with US imperialism and Soviet power

RON JACOBS welcomes an investigation of the murders of US leftist activists that tells the story of a solidarity movement in Chile

RON JACOBS welcomes the translation into English of an angry cry from the place they call the periphery