ELEANOR DOBSON reflects on a stark visual record of the violent desecration of Tutankhamun’s mummified remains

Illustration: Bryan Talbot

Illustration: Bryan Talbot

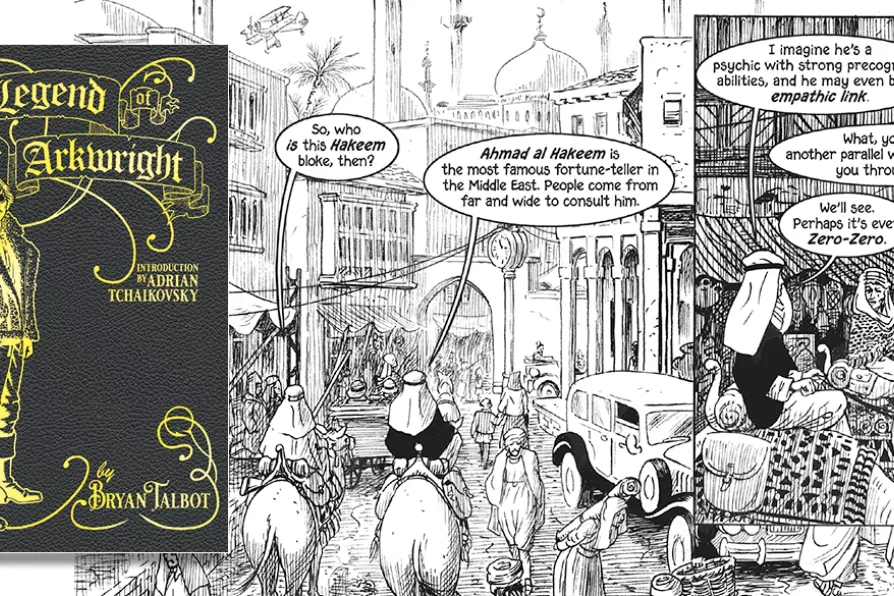

The Legend of Luther Arkwright

by Bryan Talbot

Jonathan Cape, Paperback, £20

THE graphic novel emerged from comic strip art as a popular and credible form in the early 1980s. In Britain, a key factor was the thematically complex and skilfully drawn work of Posy Simmonds, the late Raymond Briggs and Bryan Talbot.

Simmonds and Briggs gained greater media attention, but Talbot’s arresting collisions of text and image attracted a dedicated audience. His appeal lay in a disdain for genre boundaries, multi-layered narratives, and meticulously realised black and white images.

Over the years his books have explored comedy-adventure, anthropomorphic steampunk, erotica, sexual abuse and – in the magnificent Alice in Sunderland – the culture, mythology and history of a city.

The Legend of Luther Arkwright marks the return of one of Talbot’s earliest and most admired story cycles. As a “homo novus”, the next step in human evolution, Arkwright has psychic powers and travels between parallel realities. A benevolent assassin, he protects humanity from the malign influence of powerful and oppressive forces.

The original Arkwright tales (1982-1999) were a revelation, with Talbot conjuring something entirely fresh from familiar elements. The set-up drew on Michael Moorcock’s literary multiverse, as well as his steampunk aesthetic and insouciant approach to time travel. There were nods to the political provocations of Wilson and Shea’s Illuminatus! Trilogy, and the fragmented, nonlinear images were suggestive of the films of Nicolas Roeg.

The latest addition to Arkwright’s saga builds on these foundations. There is the familiar blend of extravagant adventure and bizarre invention, but Talbot’s reflections on the uses and abuses of power are more direct and unflinching.

The story opens with Arkwright fighting for survival against a being called Proteus, the androgynous herald of a step in human evolution beyond homo novus. Proteus is ruthless and self-serving – s/he deems homo sapiens a worthless species, fit for slavery or slaughter – and attempts to recruit Arkwright to a sybaritic lifestyle and war on humanity.

Resistance to Proteus’s lust for control provides the central narrative thread, but there are fascinating digressions.

Arkwright and his sidekick Harry Fairfax, a foulmouthed and grumpy former revolutionary, tramp through the battle-scarred wasteland of the Kingdom of Mercia, encountering religious mania, nationalist bigotry, xenophobia, oppression, banditry and a mass rejection of knowledge and reason. Does that sound familiar? I read this sequence as a symbolic autopsy of 21st-century Britain – the Britain of our own corner of the multiverse.

Meanwhile, the utopian world for which Arkwright is an agent faces an existential threat. The nature of this dimension, together with the history and character of Arkwright himself, is revealed through the central Proteus narrative, but also via a journalist’s memoir and history lessons tutored by an anthropomorphic AI.

FIONA O’CONNOR steps warily through a novel that skewers many of the exposed flanks of the over-privileged