ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

Correcting the record

HELEN MERCER applauds a book that restores the contribution of US communists to the Civil Rights movement

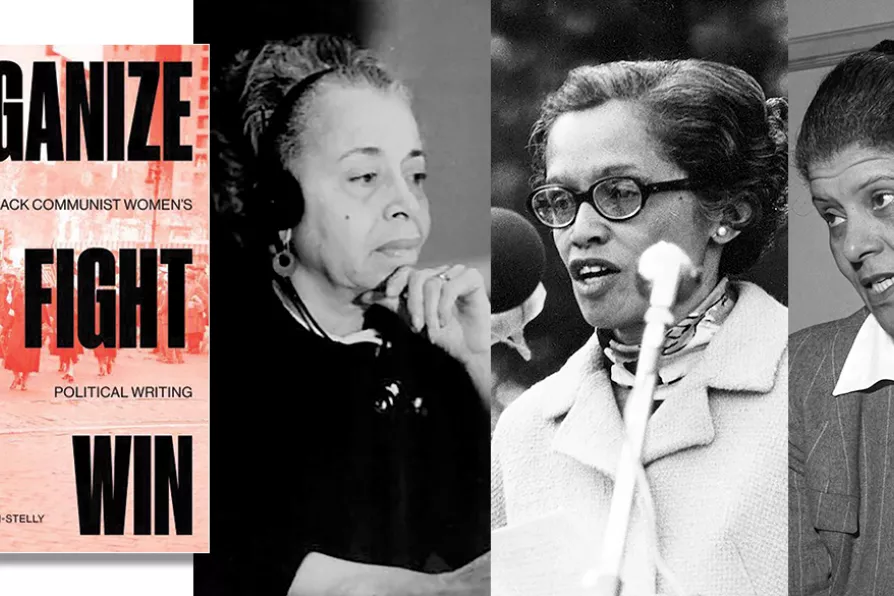

(L to R) Louise Thompson Patterson at the 7th Federal Congress of the Democratic Women's Federation of Germany in Berlin, November 1960; Esther Cooper Jackson addressing a rally in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1968; Eslanda Goode Robeson c1947

[(L to R) German Federal Archives/Public domain/Pic:digital.library.ucla.edu/Los Angeles Daily News/Public domain]

(L to R) Louise Thompson Patterson at the 7th Federal Congress of the Democratic Women's Federation of Germany in Berlin, November 1960; Esther Cooper Jackson addressing a rally in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1968; Eslanda Goode Robeson c1947

[(L to R) German Federal Archives/Public domain/Pic:digital.library.ucla.edu/Los Angeles Daily News/Public domain]

Organize, Fight, Win – Black Communist Women’s Political Writing

Edited by Charisse Burden-Stelly and Jodi Dean

Verso, £19.99

CLAUDIA JONES is well known as the driving force behind the establishment of the Notting Hill Carnival. Morning Star readers will also be aware that she was an American communist, a member of the CPUSA, and deported to Britain in 1955 having been indicted under the Smith Act.

Indictments under this Act, together with the House Un-American Activities Committee, decimated the leadership of the CPUSA as well as ruining the lives of sympathisers.

Similar stories

DAVID HORSLEY reminds us of the roots and staying power of one of the most iconic festivals around

From McCarthy’s prison cells to London’s carnival, Jones fought for peace and unity while exposing the lies of US imperialism, says ROBERT GRIFFITHS, in a graveside oration at Highgate Cemetery given last Sunday

DAVID HORSLEY points to the continued relevance of an inspirational black communist whose 110th birthday anniversary will be celebrated on Sunday

Last week the CPUSA launched a new Rapid Response project aimed at mobilising a popular resistance to policies enacted by the new government. CAMERON HARRISON explains