FOR the last 10 years in London and other Western capitals, Nike has promoted something called “Air Max Day” which is a “cultural celebration” of one of their famous models of shoe and takes place every year on March 27 — the original release date of the shoe back in 1987.

Nike enlists the help of its agents and influencers, paying them to encourage their networks to — quite literally — celebrate the birthday of a Nike shoe like it has a soul. And, of course, the only way to celebrate this mass-produced shoe (almost certainly made in slave labour conditions) on the day is by — you guessed it — buying more of the same mass-produced shoe. Thoroughly festive.

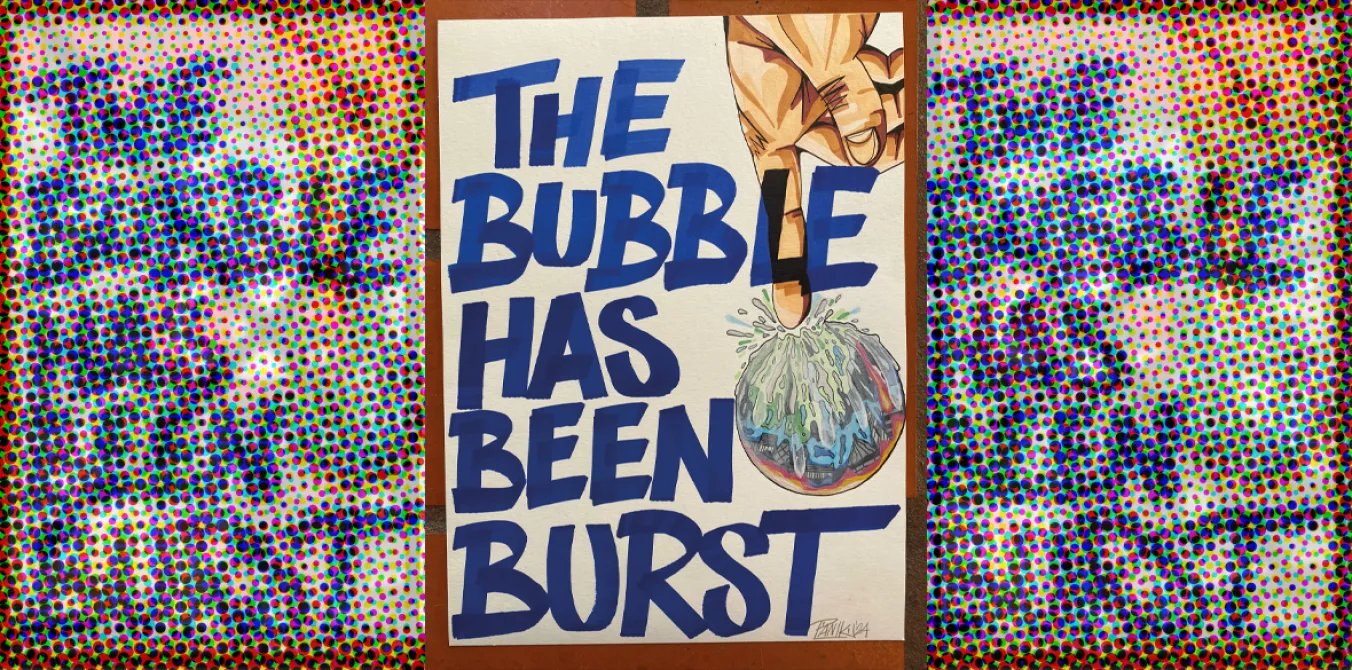

Not this year. The 10th annual Air Max Day dropped like a deflated balloon in London and hopefully marks the end of this gross display of Western complicity and privilege.

That is a result of an uprising by creatives in solidarity with Palestine, unwilling to any longer act as agents for the megabrands helping fund Israel’s genocide.

Nike still clearly felt it appropriate to ask its London agents and influencers to celebrate a mass-produced shoe owned by the warmongers of Wall Street while — along with our own government — they help fund the hell raining on the Palestinian people trapped inside a walled-off death zone, being systematically slaughtered and starved.

The handful of agents and creatives in London who still decided to take Nike’s shilling and promote Air Max Day this year were swiftly forced to remove their posts due to the now increased resistance and awareness among the creative community, and the negative press that was unfolding while these posts remained live.

Brands, street culture, complicity and resistance

The early 2000s saw the emergence of a new “creative industry” in London — one where global brands sought to buy into regional subcultures by enlisting the help of the capital’s cutting-edge creatives to sell their products and in turn secure cultural/consumer allegiance to their brands.

In 2005 I was an 18-year-old stepping into the world of work and trying to make a living as a freelance artist through my skill set which could only really be credited to having spent my entire teenage years painting graffiti pieces rather than any formal training reinforced by certificates.

Street art was booming in Britain at the time due to the groundbreaking approach of certain artists whom the liberal elite was enamoured with. It favoured the more palatable accessible street art as opposed to traditional letterform graffiti which is more coded and connected to youth criminality — therefore often less inviting or easy to package up and sell.

I’d recently started making street art following years dedicated to traditional graffiti culture. It was new, interesting and connected to the world of illustration, art and design — a world I was very keen to work in.

I was well positioned to access the streams of revenues provided by this fast-growing industry, being commissioned by companies such as Virgin and Topshop. I’d created murals for both inside their Oxford Street premises by the age of 19.

I was celebrated by my peers for these achievements and was certainly proud of them myself at the time. I was a shining example of how the neoliberal West can host your “entrepreneurialism” and “fulfil your creative dreams.” However, by the end of the 2000s, this neoliberal dream had started to look a bit ugly from where I was standing.

London was heavily sanitised ahead of the 2012 Olympics meaning the once gritty and mysterious subcultures of graffiti and even the musical genre of Grime had started being erased, demonised, oppressed through legal action or commercially diluted.

With the 2008 recession hitting people’s pockets, it was no longer easy to make a living through selling people artwork. Furthermore, austerity removed almost all government arts funding and policies to support creatives were ditched, which meant that by the time the Olympics came around it seemed the only real money available for creatives in London came from the private sector — the global brands.