The proxy war in Ukraine is heading to a denouement with the US and Russia dividing the spoils while the European powers stand bewildered by events they have been wilfully blind to, says KEVIN OVENDEN

Defending the right to strike

Ahead of a TUC special Congress next weekend to fight Conservative anti-strike laws, JOHN FOSTER looks back to 1969 and 1972 when similar proposals were defeated through class solidarity and painstaking organising work

BETWEEN 1969 and 1972 two successive attempts were made to limit the right to strike in Britain. Both were defeated.

The first was by a Labour government. In 1969 Harold Wilson produced his white paper, In Place of Strife, proposing to make unofficial strikes illegal and to punish unofficial strikers directly. Penalties were to include both fines and ultimately imprisonment.

The second was by Edward Heath’s Conservative government. Its 1971 Industrial Relations Act required the registration of all trade unions and laid down financial penalties for any union whose members were responsible for unofficial strikes deemed illegal under the Act. Strikers themselves were punishable at law for infringements of the Act.

More from this author

JOHN FOSTER examines how the late SNP leader shifted the party leftwards and upwards, bringing Scottish independence to the forefront while fundamentally failing to address deeper issues of class and corporate capture

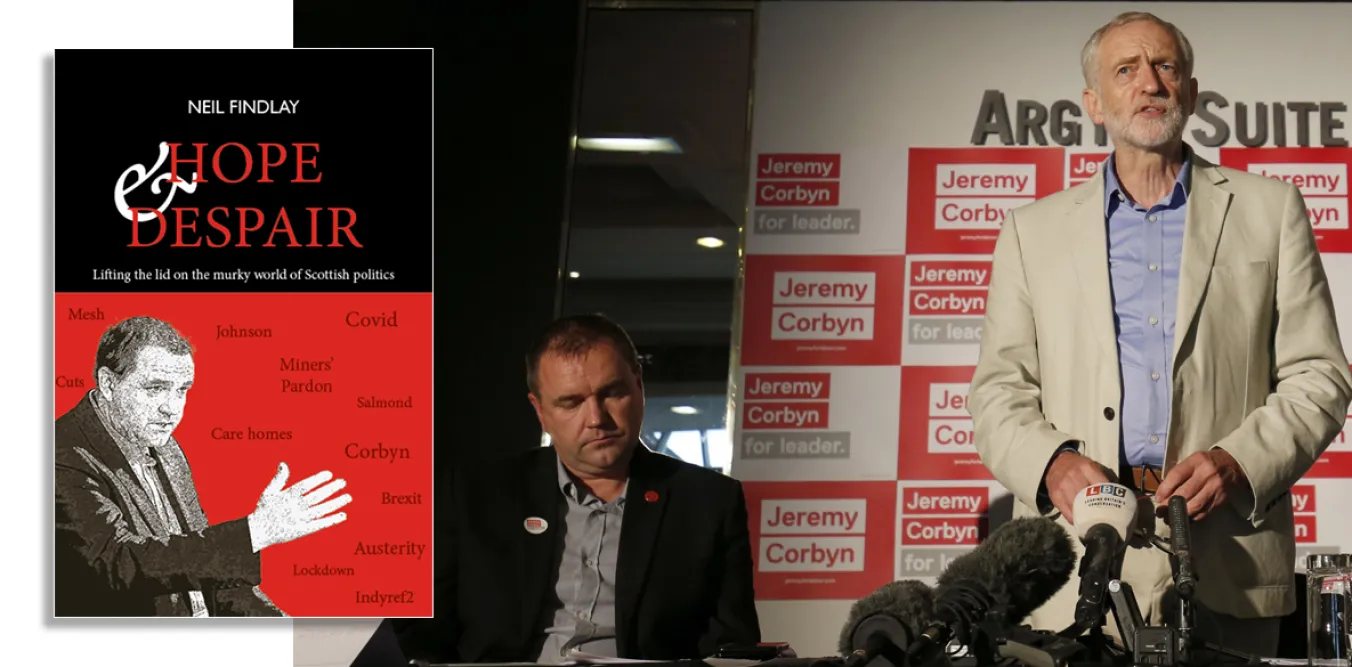

JOHN FOSTER recommends the down-to-earth realism of a political memoir that navigates the surreality of Scottish politics

JOHN FOSTER discusses the role of communists in responding to the aggressive militarisation initiated by the US in a world that faces an unprecedented period of acute crisis, as he introduces the international resolution for this autumn's Communist Party Congress

Half a century ago, 8,000 workers took over four shipyards in Scotland and instead of striking, kept working. JOHN FOSTER previews an event to mark this brave action, which not only saved every job, it turned a period of retreat into a working-class offensive

Similar stories

ROGER SUTTON reflects on the mass action that freed imprisoned dockers on this day in 1972, which is to be commemorated later this year in an event drawing parallels with the struggles of workers today

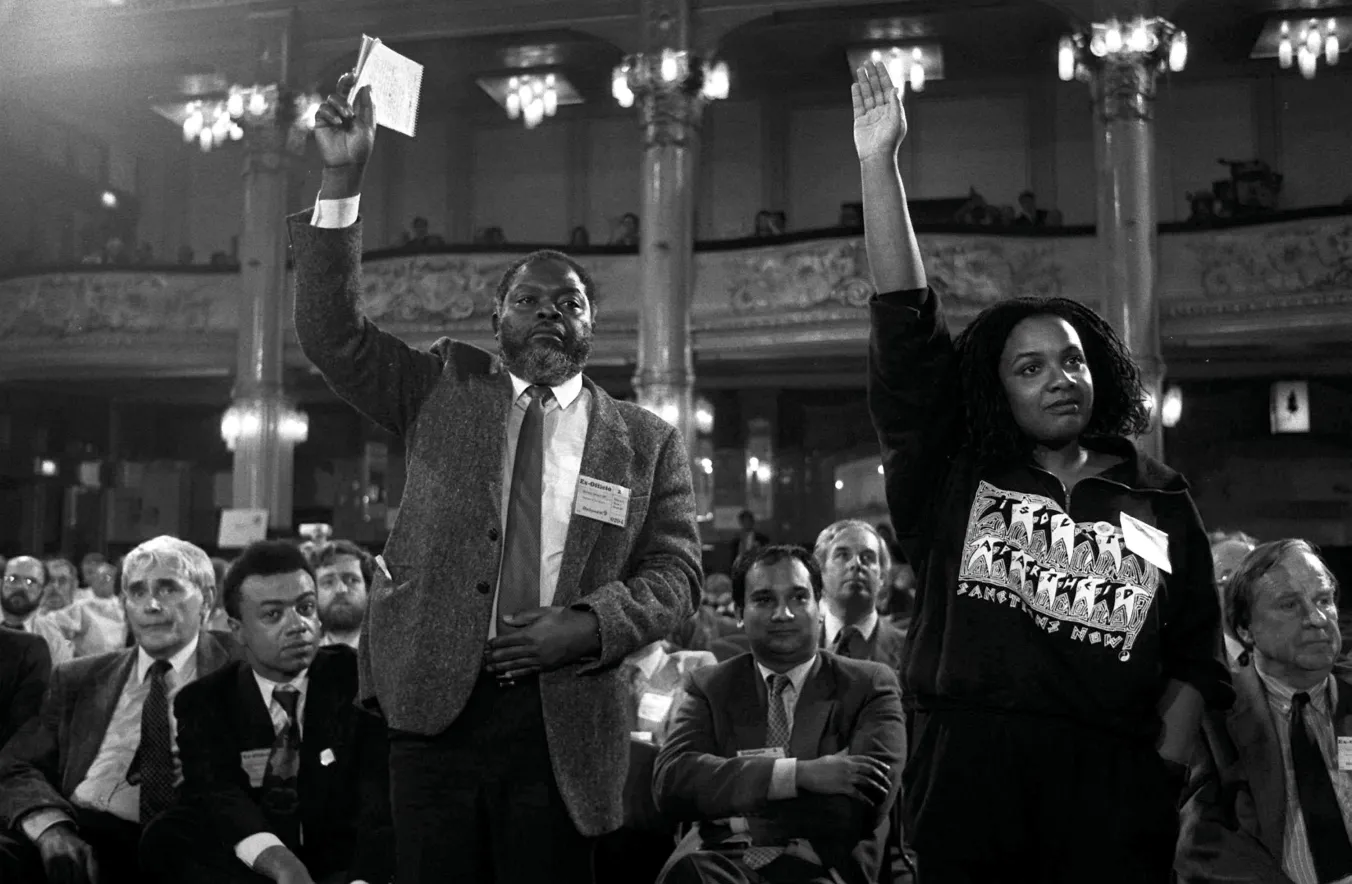

As African and Asian activists pushed back against racism in workplaces and politics in the ’70s and ’80s, eventually trade unions and political parties reluctantly opened their doors to self-organised groups, writes ROGER McKENZIE

In the second in a four-part serialisation of his new book, African Uhuru, ROGER McKENZIE outlines the organised resistance to a surge of racism against black workers in law and in the unions as they returned from the war

LORD JOHN HENDY KC explains how the events of ’84-5 were an ideological assault unleashed on the working class in revenge for gains of the ’70s