MANY years ago I read that when someone died the ancient Greeks only asked one question about the person: did they have passion?

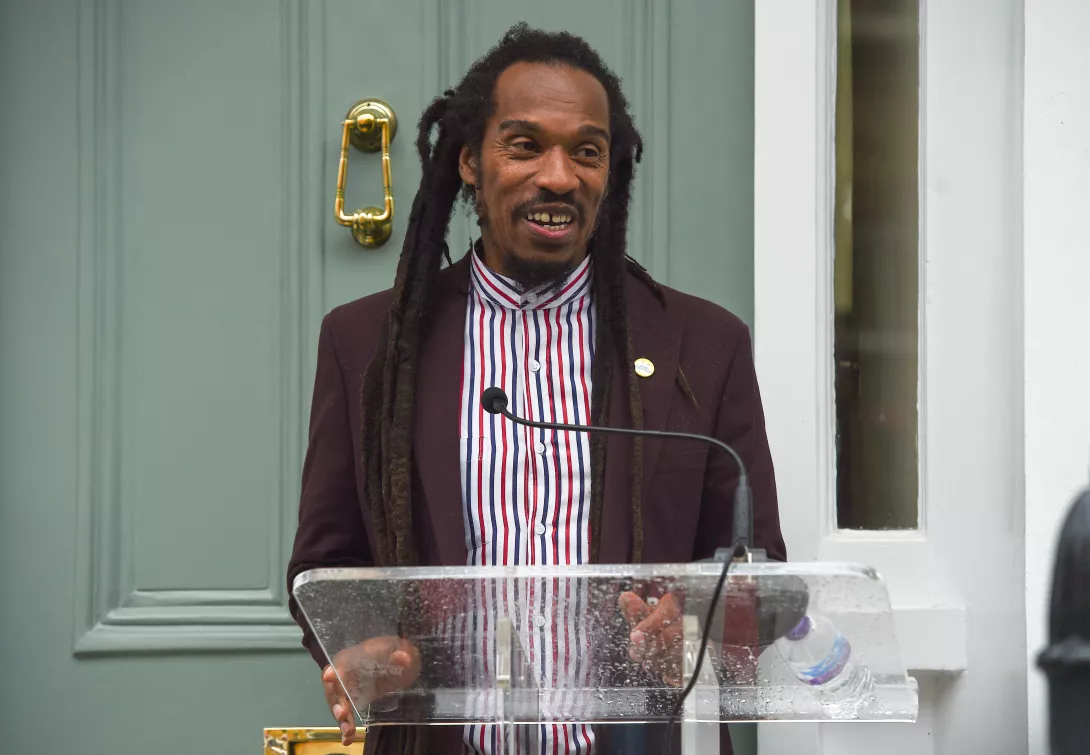

The poet — and so much more — Benjamin Zephaniah, who joined the ancestors on December 7, was a man of many passions.

Born April 15 1958 in Birmingham’s iconic Handsworth, Zephaniah, the son of Oswald Springer, a postal worker from Barbados and Leneve Wright, a Jamaican nurse, grew up in the shadow of Aston Villa Football Club.

He maintained a lifelong passion for the team after being taken to games by his uncle Simpson. He later became an ambassador for the Aston Villa Foundation.

But his early visits to the ground would not always be happy ones during a period of racism that engulfed the terraces of the great game.

He once said of the racism in and around Villa Park: “The journey to Villa Park could be arduous and dangerous. Often, as we walked to the ground holding uncle’s hand, we would be verbally assaulted with racist comments.

“When we were in the ground supporting the team we loved, the comments increased in number, and amplified in volume, and this was from people supporting the same team as us.

“I used to get very scared, but Uncle Simpson would have none of it. He always told us, “We are Villa till we die, no matter what anyone else says.”

I first read these words during my period of absence from watching football at Villa Park because of the levels of racism that surrounded you every game.

This was a big help in persuading me to return to the stadium to watch the team I have loved since boyhood. I thank Zephaniah for that and I hope that he was aware that the night before he died that our beloved Villa turned in one of their best-ever performances in demolishing Manchester City, arguably the best club team in the world.

Few black people were immune from the racism from far-right groups, the police and the casual almost routine levels of abuse from complete strangers growing up in Birmingham or, in my case, the Black Country.

Some chose to survive it or ignore it while others, such as Zephaniah, chose to tell the story and become active in the fight against racism.

They say the pen is mightier than the sword — maybe? But Zephaniah used his passion for playing with words both orally and on paper to amplify the voices of those of us who believed — because we were continually told it — that we were “less than” because of the colour of our skin.

His passionate blending of words from between the English and Jamaican patois helped white people to hear about our lives and what some were doing to us in their name.

That was, of course, gold dust. But even more important than that was the pride and the passion Zephaniah’s words built in us as black people.

His talent was not just used to just get white people to hear about racism and to somehow feel sorry for our plight as black people — and if it succeeded in doing that it would be no mean feat.

Zephaniah also succeeded in helping to straighten our backs and lift our heads as black people in a way that relatively few black people have managed outside the world of sport or music.

The fight against racism is often portrayed as being directed at the actions of white people. I feel that Zephaniah always understood that black people needed to understand the power that we had at our disposal and used his platform to help us to believe in ourselves.

But his interests were not just about tackling racism head on, they were also about other important areas of life. This helped him to make an enormous contribution towards widening the appeal of poetry.

Zephaniah was also a passionate vegan from age 13 having turned to vegetarianism from the age of 11 neither of which would have been particularly easy things to do as a child in a West Indian family during the early 1970s where the food culture is dominated by meat and fish dishes.

Zephaniah eventually became the honorary patron of the Vegan Society, the Vegetarians’ International Voice for Animals and the Evolve Campaign.

He wrote about his veganism in 2001 when he published The Little Book of Vegan Poems, helping to liberate the vegan movement from being seen as a largely white, middle-class thing to something that we should all understand the importance of for animals and the planet.

Although Zephaniah often described himself as an anarchist he was a vocal supporter of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party.

In 2019 Zephaniah added his name to a letter that said: “Labour’s election manifesto under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership offers a transformative plan that prioritises the needs of people and the planet over private profit and the vested interests of a few.”

He was also a passionate supporter of Palestinian freedom and the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement.

Zephaniah never flinched from describing the regime inflicted by the Israeli occupying forces as apartheid.

Zephaniah spoke out against the continuing horrific levels of homophobia in Jamaica, the need to scrap the first past the post electoral system, called for Britain to leave the European Union and supported many other left-wing causes.

He also turned his hand to acting, most notably in the hit series Peaky Blinders set in his home town of Birmingham.

In 2003, Zephaniah famously turned down the offer to become an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, saying: “No way Mr Blair, no way Mrs Queen. I am profoundly anti-empire.”

In his 2018 autobiography, The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah, he said: “I’m still as angry as I was in my twenties.”

Nobody reading his work can reduce it to being that of someone who is merely angry. That would do his craft as a poet a great injustice.

In his eulogy at the funeral of Malcolm X in February 1965, the actor Ossie Davis described brother Malcolm as a master teacher and that “there is no greater loss to a community than the loss of a master teacher.”

Benjamin Zephaniah was a master teacher and it is time for him to rest in power with the ancestors.

Our condolences to his family and friends from everyone at the Morning Star.