BOXING Day marks 130 years since the birth of Chairman Mao — a revolutionary whose significance seems all the greater now given the rise of China.

China’s alleged reversion to Maoism under President Xi Jinping is a recurring theme in Western media. A year ago the Guardian was quoting the US-based academic Hu Ping on how Xi was “increasingly reverting to Mao” on domestic policy; outlets from the New York Times to Al Jazeera have referred to Xi as “the new Mao.”

China is certainly celebrating Mao this winter. A new film, When We Were Young, will depict his student years; a TV series, Kunpeng Strikes the Waves, will tell the story of his early activism and discovery of Marxism. The “kun” and “peng” are mythological creatures, or one creature, since the kun, a huge fish, transforms into the peng, a huge bird, whose flight, in the Taoist classic the Zhuangzi, causes storms lasting months and churns up the sea for hundreds of miles around: an indication of how great an impact Mao is deemed to have had on China’s history.

Xi himself has promoted the “back to Mao” narrative. Shortly after his election to a third term leading China’s Communist Party last year, he took the politburo on a high-profile visit to Yan’an, the communist base area after the Long March of the 1930s, from which Mao directed much of the civil war, received Western admirers such as Edgar Snow, and which became a sort of prototype Red China before victory on a national scale in 1949.

In Western depictions, this is inseparable from a wider narrative in which China is becoming more adversarial and threatening.

Where a generation ago it was portrayed as having embraced capitalism, now the leading capitalist countries see it as an enemy its communist character is hyped up.

How real is the shift? Ofcom in 2021 revoked its state broadcaster CGTN’s right to broadcast in Britain, saying it was “ultimately controlled by the Communist Party.” China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin noted drily that Britain “knew clearly the nature of our media from CGTN’s first day of reporting in the UK over 10 years ago” and that “China is a communist country led by the Chinese Communist Party” — it was Britain, not China, that had changed its attitude.

A lot of the mainstream narrative about China is frankly nonsense. A politically motivated growth in US sanctions, obediently copied by London and Brussels, is used to claim Xi’s China has turned in on itself and is economically isolated.

But it is under Xi that China has become the biggest trading partner of two-thirds of countries and under Xi that the Belt & Road Initiative has replaced the World Bank as the largest lender of development finance worldwide.

The significant expansion of the Brics, particularly in a region — the Middle East — traditionally dominated by US imperialism, reflects an increase in Chinese international influence: as does the Chinese role in brokering renewed relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran and the linked ceasefire in Yemen. Western talk of China’s isolation is as misleading as our politicians’ use of the term “the international community,” which always means “the United States and its allies.”

Indeed, at the same time as deriding an isolationist China, Western critics attack it for being more active internationally.

Xi’s Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative and Global Civilisation Initiative are presented, when mentioned at all, as threats.

In a way they are challenges to the Western world order, as China expert Jenny Clegg has outlined, the first pushing an economic development model that would end subordinate status for the global South, the second calling for an international security architecture that prevents “might is right” geopolitics on the Nato model, and the third promoting the equal value of different civilisational traditions, when our current international architecture and law are derived exclusively from the European tradition.

This challenge to the West takes its place in the “back to Mao” narrative, because Chinese leaders since Mao have adopted a lower profile on international questions. Xi said in 2017 that it was “time for China to take centre-stage in the world... standing tall and firm in the east.”

The Financial Times went to Christopher Johnson of Washington’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies, one of those think tanks, bankrolled by the US state and armaments giants like Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, which provides neutral experts for our TV screens and newspaper pundits.

Johnson said Xi was turning his back on the “reform and opening up” era that began with Deng Xiaoping in 1978: “Deng would never have said anything like that.” Xi was said to have betrayed Deng’s famous dictum that China should “hide our strength and bide our time.”

The phrase “bide our time” does come with an in-built time limit though. Is Xi abandoning Deng’s strategy, or simply taking the next step?

China portrays the rise of the Brics as a means of ending the domination of the old imperialist powers, and in this sense Xi is adopting a decolonising mantle inherited from Mao. Mao’s China was a key organiser of the 1955 Bandung conference, an attempt by formerly colonised countries to promote an alternative blueprint for international politics.

Ahead of the 60th anniversary of Bandung in 2015, China published transcripts of three meetings between Mao and Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru that paved the way for the conference, an attempt to revive the notion of co-operation between the two largest Third World countries against the West in the cause of global decolonisation.

Authors like Carlos Martinez in The East is Still Red point out that the idea post-Mao China decisively broke with Mao is not one which has ever been accepted by Chinese leaders.

When the newly elected President Xi said in 2013 that “the 30 years of reform and opening up cannot negate the previous 30 years” (of revolution led by Mao) it was reported here as signalling a policy shift, but plenty of quotes from Deng or his successors make the same point.

In 2003, then president Hu Jintao praised Mao for delivering “the most profound and greatest social changes in Chinese history.” It was under Deng that the party issued the famous verdict that Mao was 70 per cent right and 30 per cent wrong.

Nor did China’s shift left begin with Xi. The negative impact of marketisation on workers’ rights was recognised by the Hu government, and these were significantly strengthened by the Labour Contract Law of 2007. Hu’s 10 years as leader saw social security and healthcare spending expand roughly fivefold.

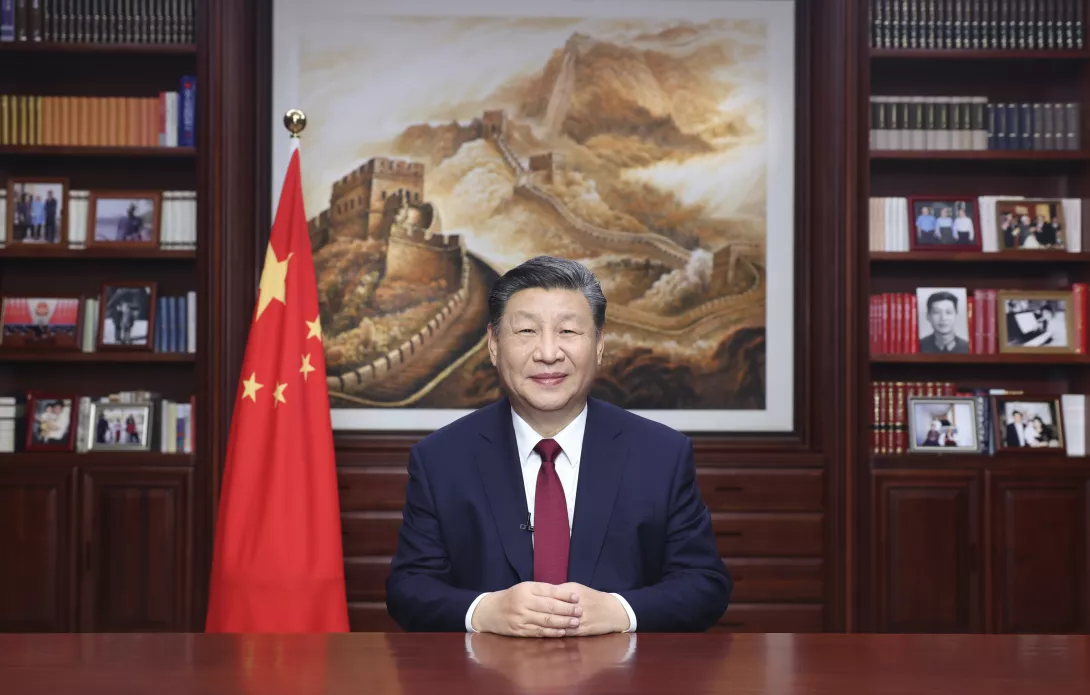

[[{"fid":"60387","view_mode":"inlinefull","fields":{"format":"inlinefull","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Xi Jinping has moved China left","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Xi Jinping has moved China leftwards"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"inlinefull","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Xi Jinping has moved China left","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Xi Jinping has moved China leftwards"}},"attributes":{"alt":"Xi Jinping has moved China left","title":"Xi Jinping has moved China leftwards","class":"media-element file-inlinefull","data-delta":"1"}}]]

Nonetheless, Xi has genuinely moved Communist Party policy leftwards. His “new development concept” subordinates economic growth to fairness and environmental and ecological considerations. A dramatic example was 2021’s 10-year moratorium on all fishing in China’s biggest river, the Yangtze: something accompanied by billions of pounds’ support for the fishing communities affected.

The market is treated with more suspicion than previously. Two years ago almost all private education and tutoring was banned, a move justified as a means to advance equal access to education for all students — and of better regulating children’s study-life balance to improve mental health.

China’s sweeping restrictions on online gaming, including age-graduated limits to the time people may spend online, are derided as nanny-state authoritarianism in the West — but do represent a serious effort to address the alienating impact dependence on virtual social interaction can have on a generation “raised online.”

Even more than the policy aims, the methods deployed under Xi have echoes of Mao’s “mass line” politics, depending on popular mobilisation to achieve them.

The biggest achievement of Xi’s government to date — the complete elimination of absolute poverty — relied on such tactics, with millions of party members tasked with spending set periods each year deployed to deprived regions, working with the locals but also ensuring they were properly informed about benefits, funding and grants that could be made available, both in terms of investment in the area generally and for individual or family needs like housing repairs.

Along with a focus on raising incomes at the bottom, Xi has sought to foster a more egalitarian ethos, cracking down on billionaires and calling for the government to regulate “excessive incomes” at the top. He contrasts China’s pursuit of “common prosperity” to “some developed countries [which] due to their social systems, have not solved the problem... [where] the disparity between rich and poor has become ever more serious.” However, new property taxes he has called for have encountered resistance, and China’s top income tax rate is the same as Britain’s (45 per cent), hardly Mao-style equality.

Xi has promoted a volunteering culture, exhorting students to spend their holidays in poorer rural regions working on development projects, and twinned rich areas with poor ones with legal obligations for the former to invest in the latter.

Rusticated himself in the “down to the countryside” movement under Mao, Xi has written about its psychological impact on him: while his accounts don’t pull punches on the pain of his denunciation by Red Guards during the cultural revolution (during which his sister committed suicide), he also argues that his years in the countryside gave him a sense of purpose and a determination to improve the lives of China’s poorest people.

Last year he called for a “rural revitalisation” movement, encouraging urban graduates and businesspeople to relocate to their ancestral home towns. It’s a shift, but again, the extent to which it departs from the long-term plan of figures like Deng is questionable.

In the 1980s Deng explicitly defended focusing on certain provinces’ development first — Guangdong and Fujian being pioneers of “reform and opening up” — on the grounds that “some will get rich first,” but those who did would then be required to give a leg-up to those who didn’t.

The whole concept of China utilising market forces and foreign capital during the “primary stage of socialism” was justified, from the start, as a means to build up the productive forces for socialist distribution on a richer material basis. Though most Western observers assumed this was merely an excuse for continued Communist Party rule over a capitalist country, Xi’s policies conform precisely to what the party said it was intending to do all along.

If Xi echoes Mao, it is perhaps because the questions which absorbed the Chairman, from wealth differentials to China’s role as a leader of the decolonisation movement, are as acute today as they were 50 years ago: with the rise of the global South possibly a greater challenge to imperialism even than the Soviet Union was.

When the histories of how the historically brief supremacy of the West came to an end are written, it seems a fair bet that both Mao and Xi will have starring roles.