THE horrific death toll among Palestinian journalists is staggering. Less easy to comprehend is just how exceptional is the scale of slaughter. So, for context, I compared the most up-to-date lists of the dead with the mortality rate among combatants in recent wars — and the results are truly shocking.

At the start of the Israel-Gaza war, there were approximately 1,000 journalists working in the enclave. Movement in and out of Gaza has been severely restricted for many years, so we know that there were no international journalists among them, although some are employees of international news platforms.

Since October 7, the deaths of Palestinian journalists has been an almost daily occurance. There are various measures of the total media death toll, the International Federation of Journalists puts to total as 75 — but with slightly different methodologies, other tallies reach just over 100.

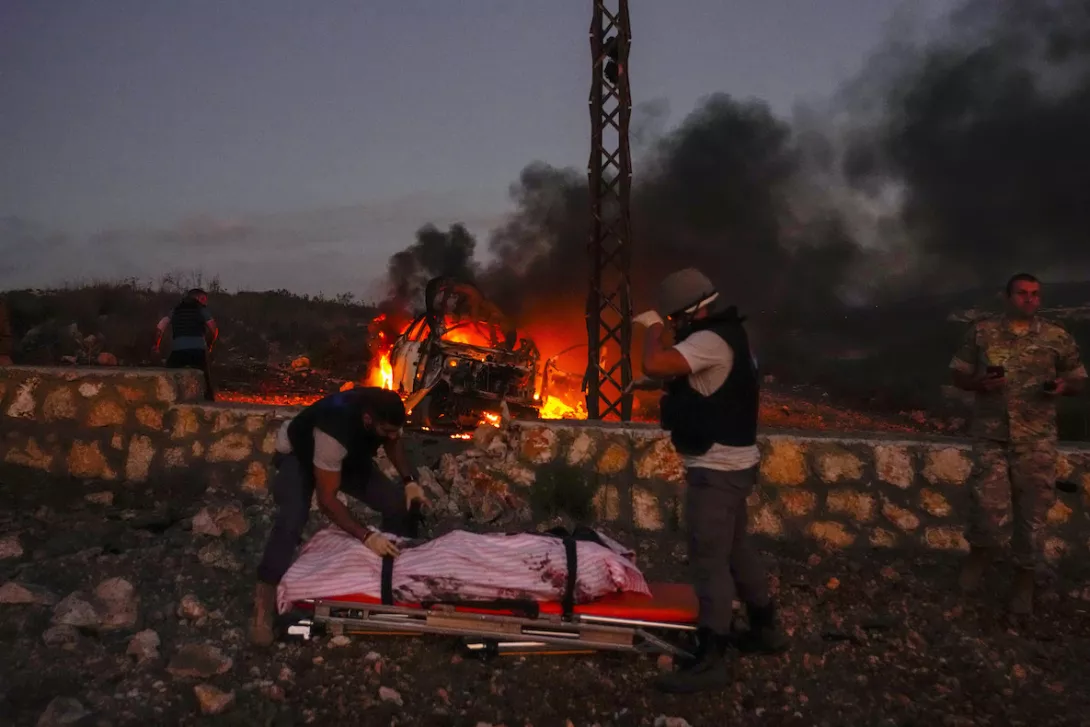

There are also, of course, the four Israeli journalists who died in the October 7 attack, and two Lebanese who lost their lives in a rocket attack close to the Egyptian border.

Seventy-five Gazan journalists dead means a mortality rate of 7.5 per cent.

Based on figures from the United States Department of Veteran Affairs: in Korea, 1.4 per cent of US soldiers lost their lives in battle; in Vietnam, 1.7 per cent of US soldiers lost their lives: in World War II 1.8 per cent lost their lives, and in Desert Storm 0.06 per cent lost their lives.

According to figures from the American War Library, the mortality rate among members of the US Marine Corp in Vietnam — the soldiers most likely to have been involved in the fiercest combat — was five per cent.

Armed with cameras, microphones and note pads, Gaza’s journalists are facing the most ferocious onslaught from one of the world’s most sophisticated armies.

It is worth remembering the many differences between soldiers and journalists. The former are intensely trained in avoiding and reacting to injury. A macabre science of warfare exists whereby likely casualty rates are calculated by military top brass to determine how many medics are required by each platoon, and how much medical equipment need be carried into battle. Military casualties can expect medical attention in less than hour and all studies recognise that survival rates depend on effective evacuation procedures.

Journalists have none of that. It was humbling to learn before the festive break that Gazan photographer Mohammed Balousha saved his own life with a blast trauma pack that the IFJ helped supply, after snipers shot him twice in the legs. Such kits are no match for the medical facilities available to a professional army, however.

Deaths among journalists themselves tell only half the story, of course. Nearly all have lost their homes, hundreds have lost family members and all have insufficient food and water. With no fuel, they carry their equipment on their shoulders from story to story, And, with no international reporters allowed into Gaza, they provide the only access the world has to life in the enclave.

Most Gazan journalists believe that they are being deliberately targeted by the Israeli Defence Forces, and many say that they have received threats by phone from callers saying that they represent the IDF.

It begs the question — what possibly can be done to halt this slaughter?

Pressuring those governments that support the Israeli offensive is one hope. Karen Attain, a columnist in the Washington Post, wrote recently: “The killing of journalists is an assault on memory, truth and Palestinian culture. The tacit blank check given to Israel to eliminate civilian targets, including journalists it doesn’t like, puts anyone covering the region in danger.”

Such sentiments on the op-ed pages of a major US newspaper represent shifting opinions, even among those whose first instinct is to support Israel.

Second, the International Criminal Court must be encouraged to broaden its the inquiry into the treatment of journalists by the IDF. This investigation was launched in response to the May 2022 killing by Israeli soldiers of Al Jazeera journalist, Shireen Abu Akleh. Progress has been slow, but Karim Khan, the ICC’s chief prosecutor met recently with leaders from the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate and assured them he intended his investigations to be thorough.

Khan is British, and is known to value his domestic reputation. That provides an opportunity to keep his mind focused.

Finally, Gaza’s journalists are desperately in need of tents, sleeping bags, phones, batteries, fuel and food. Their union, the PJS, is the only agency to have successfully channelled aid to them since the conflict began.

Getting anything in has become more difficult by the day. Hopefully, the next time that Rafah opens, a proper delivery of supplies will be possible. Ensuring that as much as possible can be shipped in, of course, depends on the generosity of those who continue to respond to the IFJ’s special appeal.

The fate of Gaza’s journalists is a humanitarian catastrophe — but it is more than that. With the closure of the borders to international reporters, clampdown on dissenting opinions in Israel, and the unprecedented scale of killing we are seeing one of the most bloody and brutal suppressions of free speech in the modern era.

Against this horrific backdrop, Palestinian journalists have worked through fatigue, hunger, bereavement and mortal danger to document what has befallen the enclave. Without our collective and determined support, these vital witnesses will be lost.

Tim Dawson is deputy general secretary of the International Federation of Journalists.