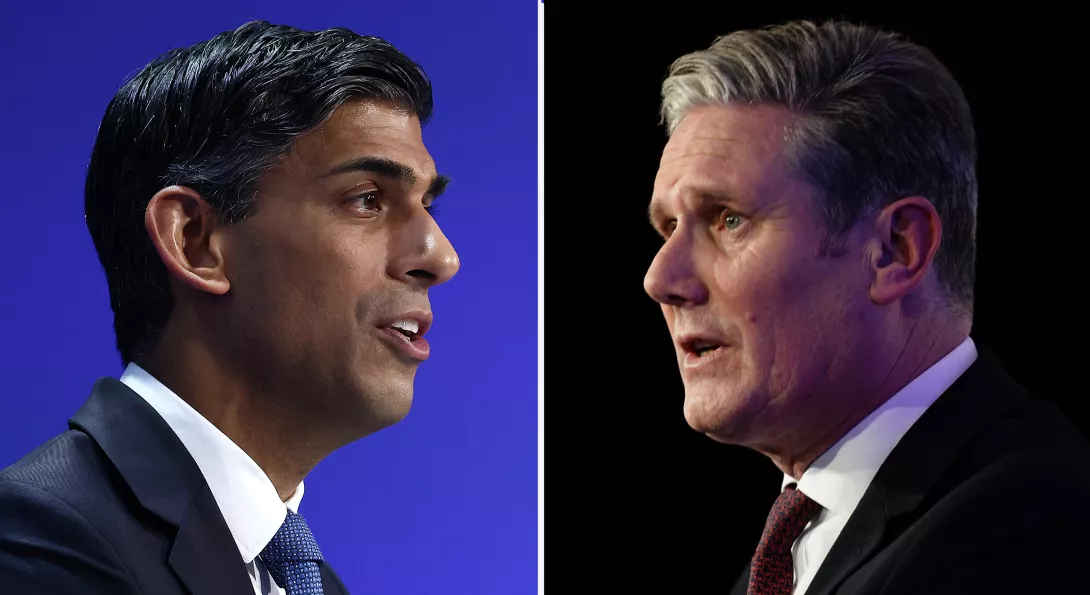

2024 is almost certainly a general election year. Westminster rumours of a May poll are rife, but the autumn remains the more likely option for beleaguered premier Rishi Sunak.

An essential function of a democratic election is to offer the possibility of a change of government. The forthcoming contest, however, seems to offer little more than a shift in administrators of the same anti-popular policy.

The problem facing voters wanting significant change — the majority of the electorate one can assume — is the state of the Labour Party. On the most pressing international issues — Palestine and Ukraine — its policy is identical with the Tories: war and more war, as Washington directs.

Domestically its priority is sticking within the narrow parameters of Treasury orthodoxy. Anything involving spending public money is, even after 13 years of austerity, ruled out. So too tax rises on the rich.

The Green New Deal is diluted further by the day, and privatisation looks like extending its tentacles into the NHS.

Even more positive Labour policies, like extending trade union rights, are clouded by a scepticism as to Keir Starmer’s sincerity, given his well-earned reputation for dissimulation and double-dealing.

Labour MP Jon Cruddas, a former adviser to Tony Blair and champion of “Blue Labour,” has put his finger on the problem.

In an essay published over the new year period, he drew attention to Starmer’s ethical vacuity, his indifference to inequality, redistribution and freedom alike, his policy U-turns and factional authoritarianism.

Cruddas rightly points out that “it is difficult to identify the purpose of a future Starmer government — what he seeks to accomplish beyond achieving office.”

The left has been here before, of course. Tony Blair’s New Labour was able to capitalise on the revulsion against the Tories after 18 years of their rule.

Blair, however, was at least honest about his intentions, which were to give the “Thatcher settlement” a humane façade and little else. He was also a charming and charismatic campaigner in opposition.

Starmer, by contrast, is a proven liar and “he has only one facial expression — the blank, startled gaze of a badger in the headlights — and no perceptible sense of humour” in the cruel but accurate judgement of a Telegraph columnist this week.

This may not matter when polling day comes. The country has turned decisively against the Tories and Labour should be the automatic beneficiary.

But the warning from Cruddas is apposite — without values and a clear policy offer “a party of labour could be destroyed by victory.”

That is the danger the left needs to confront in 2024 — an election drained of hope and positive purpose leading to a Labour meltdown in office.

Labour’s decomposition has been accelerated by its staunch backing for Israeli slaughter in Gaza. If the Gaza war is protracted, as Netanyahu threatens, and Labour’s line does not shift, the party risks collapse in some communities.

Multiple election challenges from the left, some with much more substance and prospects than others, are being mooted.

The most significant developments to watch will be Jeremy Corbyn’s decision in Islington North, challenges to Labour warmongers within alienated Muslim communities, and whatever may emerge from the large-scale defection of local councillors from Labour across the country.

However, there is scant sign of Labour’s affiliated unions rethinking their relationship to the party, whatever private discontents there are.

Under those conditions, left electoral interventions need to be targeted and unified to the greatest extent possible, so that real pressure can be exerted on the Starmer clique and the politics of peace and social justice secure a substantial hearing when the election comes.