THE most famous slogan associated with Lenin is “Bread, peace and land” — the simple demands posed after Russia’s February revolution in 1917 overthrew the tsar but when the working class and peasantry still faced the privations of war. The October Revolution, led by the Bolsheviks, took Russia out of the first world war.

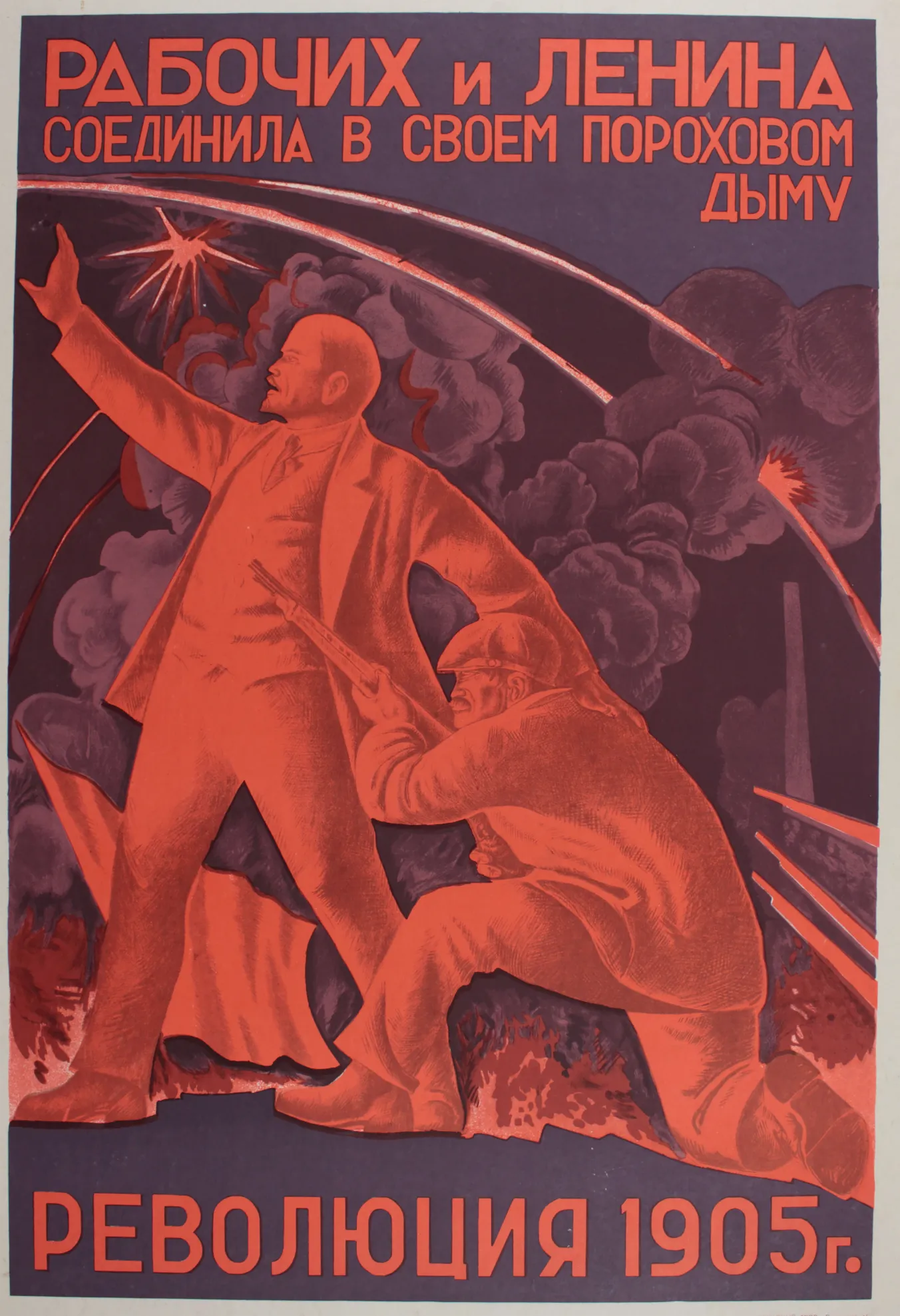

Opposition to war was not new to Lenin or to the socialists of Europe. His political activity developed as a new and terrifying era of wars was beginning: the Spanish American war which began in Cuba in 1898, the Boer war between Britain and the South African Boers in 1900, and the Russo Japanese war in 1904, where Russia’s defeat led directly to the 1905 revolution, the “dress rehearsal” for 1917.

These wars marked the beginning of a new era of imperialist war. The latter part of the 19th century had been characterised by expansion of capital throughout Europe and North America. In addition it was the era of a new colonialism — notably the “scramble for Africa” where a number of European powers grabbed the land and resources of the continent.