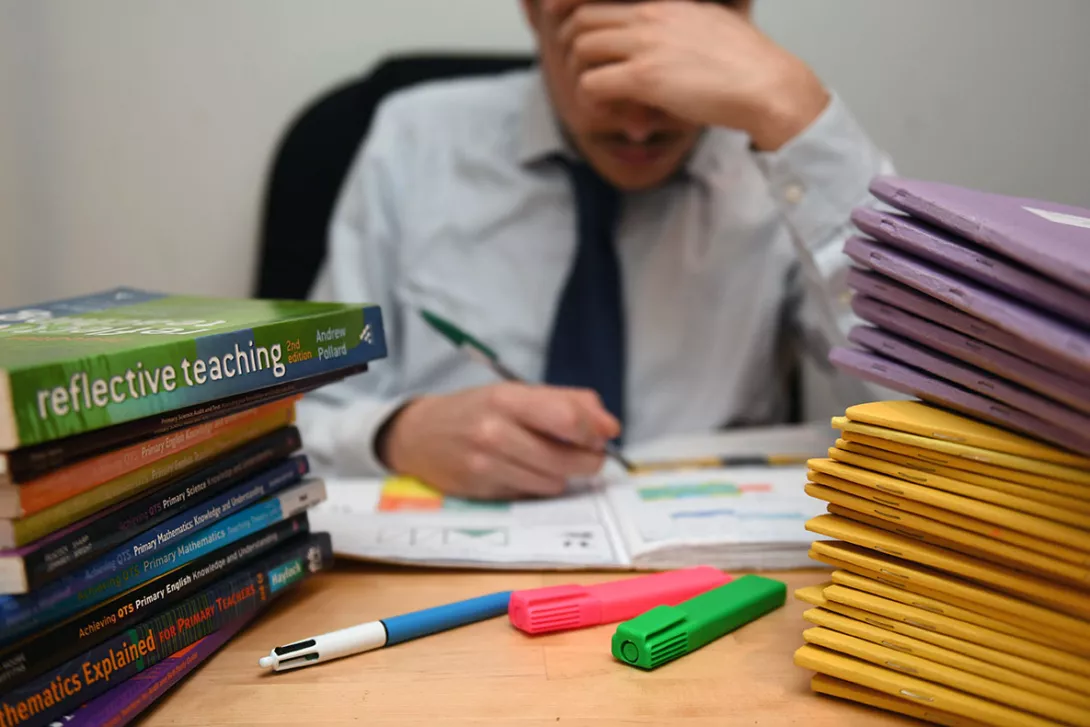

RENEWED focus on the crippling impact of PFI debt on schools and hospitals is welcome given the prospect of an incoming Labour government trumpeting “partnership” with business.

Britain’s public realm — institutions and services that keep the country running — is stricken. It is breaking down wherever we look, from the seven-million-long NHS waiting list to crumbling school and hospital buildings, from dentistry to Royal Mail, from transport to the councils lining up to declare bankruptcy.

Labour’s contradictory position is that these crises are the product of Tory mismanagement of the economy, but the only way to fix them is to stick to Tory spending plans, ruling out a wealth tax, increases in corporation tax or other measures that could fund increased spending.