The proxy war in Ukraine is heading to a denouement with the US and Russia dividing the spoils while the European powers stand bewildered by events they have been wilfully blind to, says KEVIN OVENDEN

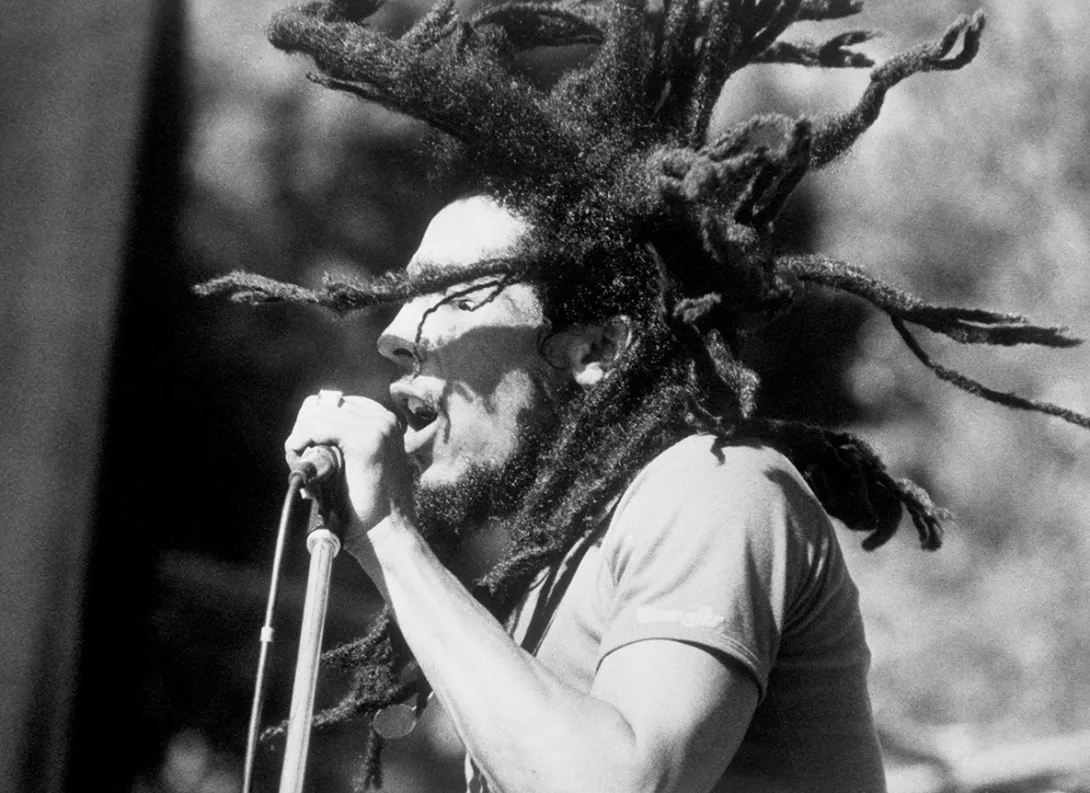

Bob Marley revisited: we have still not ‘emancipated ourselves from mental slavery’

The new biopic of one of music’s all-time greats brings into focus Jamaica’s struggles with neocolonial debt, crippling poverty, and unchecked gang violence. Nothing has changed — and that’s little to dance about, writes ROGER McKENZIE

LAST weekend I managed to go and see the new movie Bob Marley: One Love.

As a child of Jamaican-born African descendants who remembers the era talked of in the film all too clearly, it brought back many memories of my parents being concerned about the wellbeing of our family having to live through the gang violence that wreaked havoc on the beautiful island.

No — this is not a review of what I think is a very good film. Rather, the movie evoked so many memories of the power of Marley’s music and the pride that it gave those of us of Jamaican descent at a time when in Britain we were faced with constant racism at school or work and the threat of attack from racists in the street or our homes.

More from this author

ROGER McKENZIE looks back 60 years to the assassination of Malcolm X, whose message that black people have worth resonated so strongly with him growing up in Walsall in the 1980s

ROGER McKENZIE welcomes an important contribution to the history of Africa, telling the story in its own right rather than in relation to Europeans

Similar stories

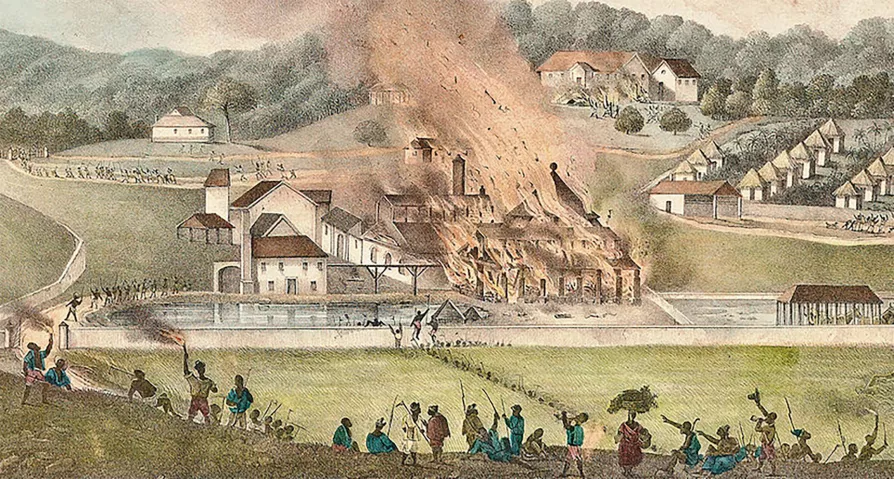

ROGER McKENZIE recommends the work of the 20th-century Marxist activist, a founding member of Jamaica’s People’s National Party and a historian whose books showed the primacy of slave revolts in ending slavery itself

The Villa forward has decided to step away from Jamaica, blasting the team as ‘unprofessional.’ JAMES NALTON reports