VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

Colleges: centres of working-class confidence

As college workers return to picket lines across the country they’re fighting for more than just a decent wage, or even their jobs, writes MATT KERR

I WAS still at school when I heard the new prime minister, John Major, proclaim his ambition to create a “genuinely classless society.” Some at the time wondered of this was a softening of the Tory position — “at least he’s accepted there is such a thing as society,” they thought.

Much is made of the so-called Thatcher revolution that he inherited, but what came next was something just as pernicious.

A decade earlier, Michael Foot had once compared the actions to at best allow, and at worst positively encourage the collapse of British industry, by Margaret Thatcher and her very own Rasputin, Keith Joseph, to that of a failed conjurer who has smashed an audience member’s watch only to have “forgotten the rest of the trick.”

More from this author

ROS SITWELL reports from a conference held in light of the closure of the Gender Identity and Development Service for children and young people, which explored what went wrong at the service and the evidence base for care

ROS SITWELL reports from the three-day FiLiA conference in Glasgow

ROS SITWELL reports on a communist-initiated event aimed at building unity amid a revived women’s movement

London conference hears women speak out on the consequences of self-ID in sport

Similar stories

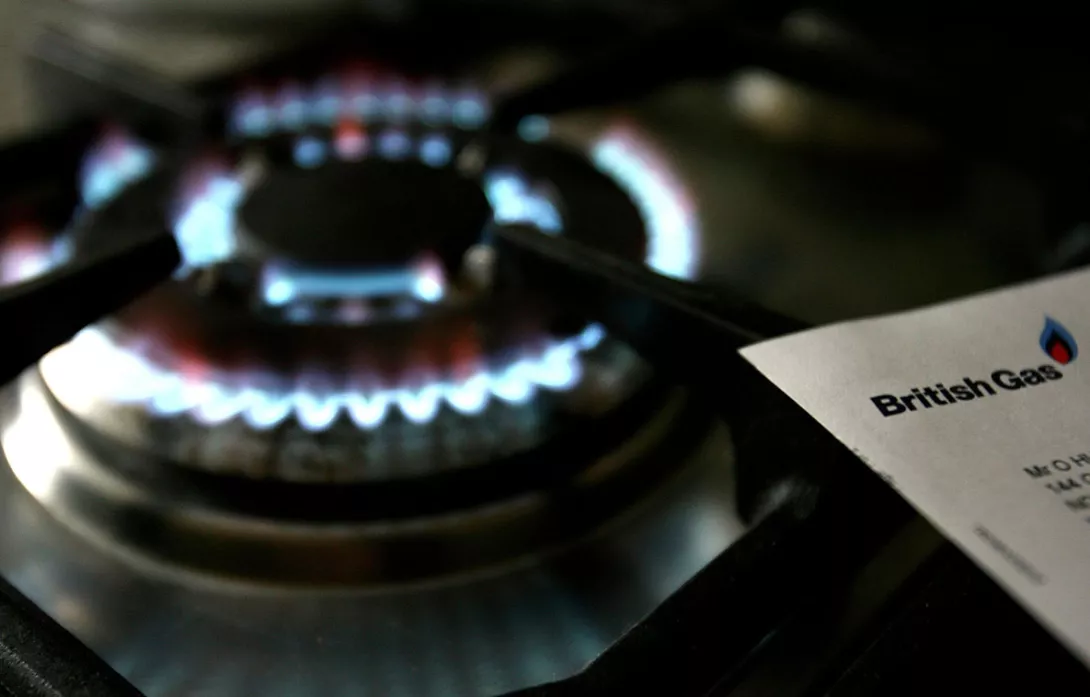

Genuine public control of essential services and a democratic renewal are worth fighting for, argues MATT KERR