VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

Financial Services Review: Labour snuggles deeper into bed with the City

Champagne receptions all about ‘growth’ under a Labour government that don’t include any plans for actual productive growth and a load of PFI-tainted spivs says it all, laments SOLOMON HUGHES

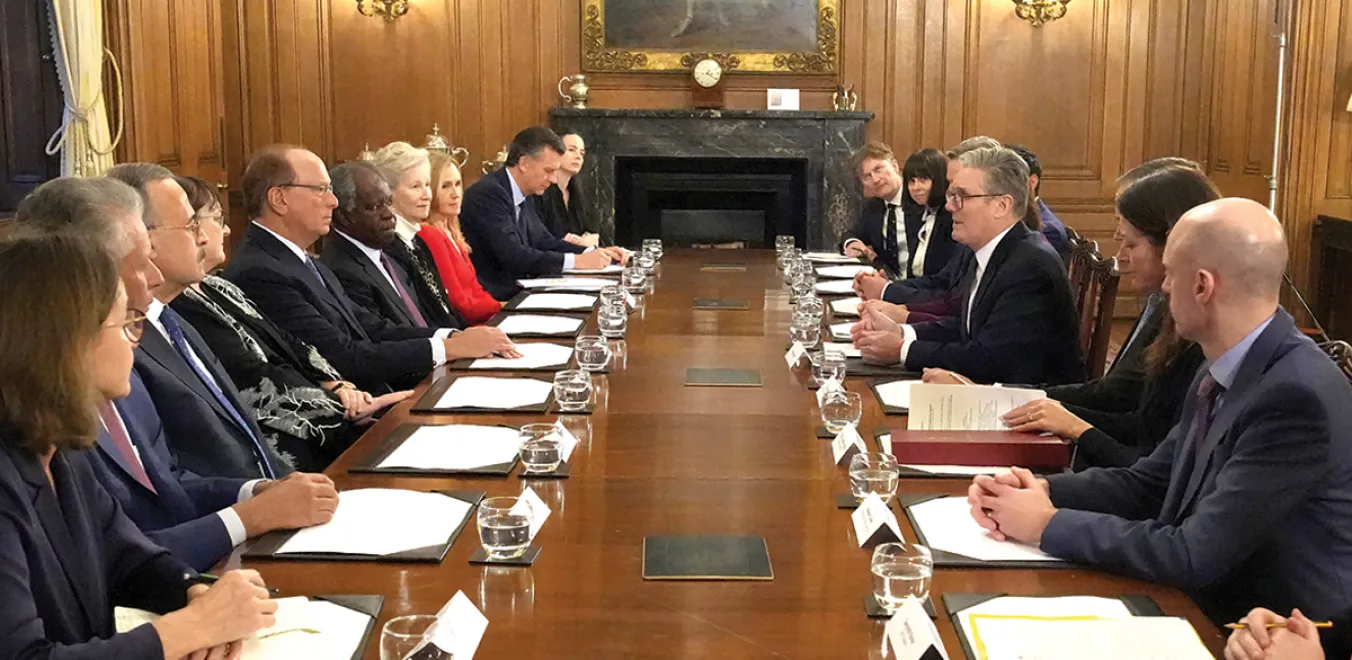

RACHEL REEVES, Labour’s shadow chancellor and shadow City minister Tulip Siddiq hosted a champagne reception at the Guildhall in the City of London for “industry leaders” in finance at the end of February.

The drinks reception was held “in partnership” with the City of London to celebrate Labour’s Financial Services Review. Ordinary members weren’t invited. Journalists were excluded.

This Financial Services Review says: “Labour’s defining economic mission is to restore growth to Britain. This calls not just for a change in government, but a change in mindset: an active government prepared to work in partnership with business to remove the barriers to economic success.”

More from this author

SOLOMON HUGHES probes the finances of a phoney ‘charity’ pushing the free schools and academies agenda

What’s behind the sudden wave of centrist ‘understanding’ about the real nature of Starmerism and its deep unpopularity? SOLOMON HUGHES reckons he knows the reasons for this apparent epiphany

They’re the problem it’s them: SOLOMON HUGHES on the freeloading flunkies of the Labour Party hoovering up VIP tickets to musical and sporting events

SOLOMON HUGHES examines how Labour has gone from blaming Tory deregulation for our economic woes to betting the nation's future on more of it

Similar stories

Keir Starmer’s BlackRock enthusiasm is a clear give-away for Tory continuity plans, argues CLAUDIA WEBBE

SOLOMON HUGHES warns Reeves’s proposed national wealth fund hands City financiers control over billions in public money for big business — and we get... to pay!

Labour seems to think we’ll be impressed about this new defector — but even a cursory glance shows he’s a professional neoliberal lobbyist, not some 'traditional One Nation Tory' concerned with social justice, reveals SOLOMON HUGHES