Creativity is at the heart of a healthy society

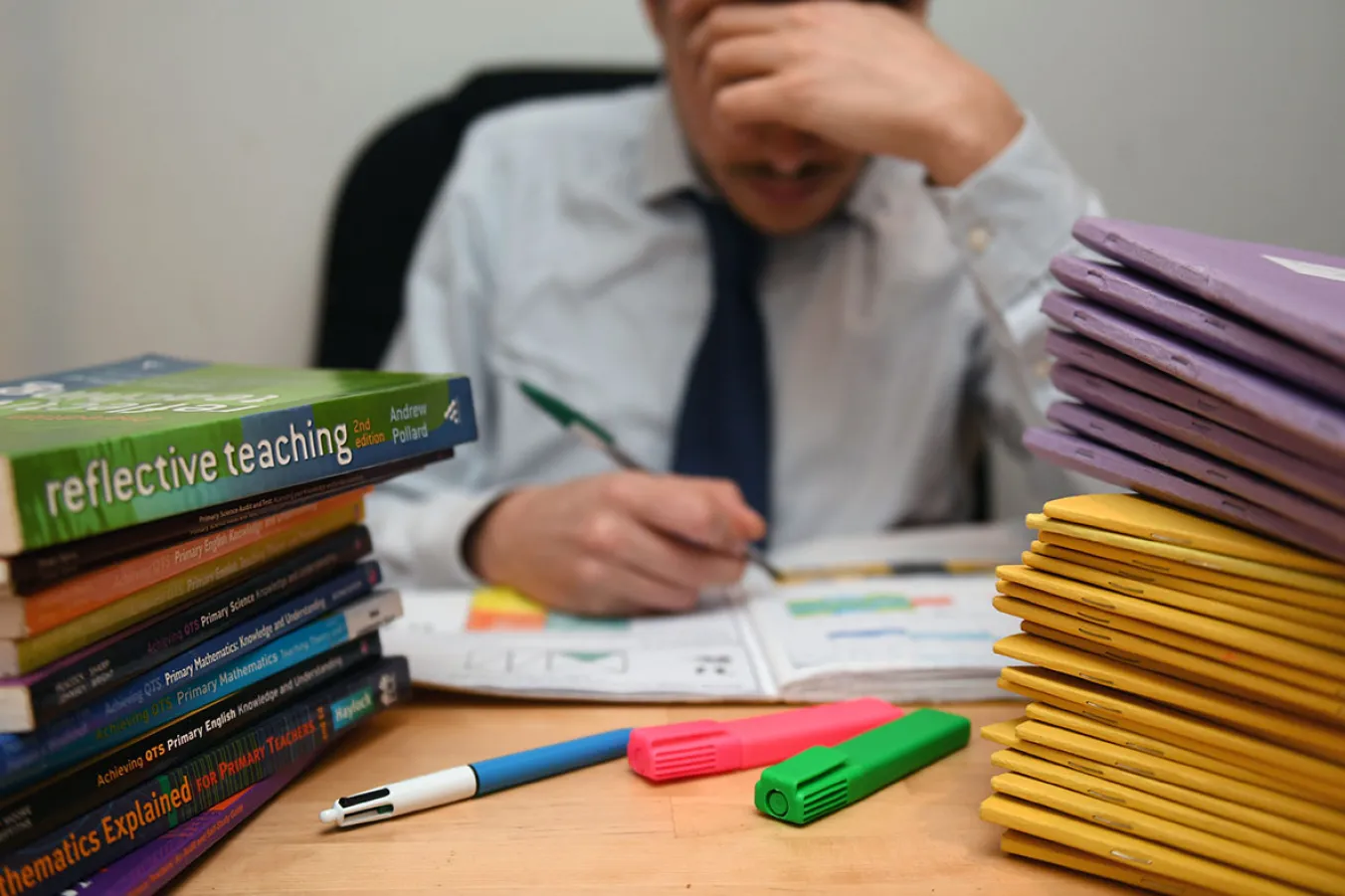

PETE STEVENSON is concerned that children have an extraordinary capacity to innovate, but they are encouraged by teachers and parents to grow out of creativity, to leave it behind to the detriment of society as a whole

I WORK as a teacher in schools promoting the values of cultural diversity and race equality through interactive storytelling workshops. It’s great to feel part of ongoing projects to challenge racism, which is sadly active in many parts of the country.

However, as I was packing away my African drums and glove puppets one afternoon, a teacher said: “It’s good to give the children something different, something fun.”

I reflected on this as I drove away and thought: “Is that what I do, just give them fun experiences? Surely I do more than that?”

More from this author

As part of the recently re-formed Exeter Stop the War Coalition, PETE STEVENSON explains how talented artist Becca Edwards engaged young people in a collaborative painting for Palestine

PETE STEVENSON compares Don’t Look Up, the most recent offering by the network, to Armageddon classics and finds it wanting on several counts

PETE STEVENSON tells a positive story of a community who fought back after a homophobic and misogynist hate crime in the harbour town of Watchet

Similar stories

Artists are frequently first in line when it comes to cuts, but society as a whole is left all the poorer – it’s time they were properly valued, says ZITA HOLBOURNE of Artists Union England

ROBERT POOLE dissects Labour’s plans around education