IN 2023, the Church Commissioners, the financing arm of the Church of England, published their Research Into Historic Links To Transatlantic Chattel Slavery.

This acknowledged the church’s historic complicity in trafficking in enslaved Africans through the profits it made from a fund known as Queen Anne’s Bounty, which was established in 1704 by Queen Anne to help poor Anglican clergy. This fund, invested in African chattel enslavement took donations derived from investments made by the church in the South Sea Company.

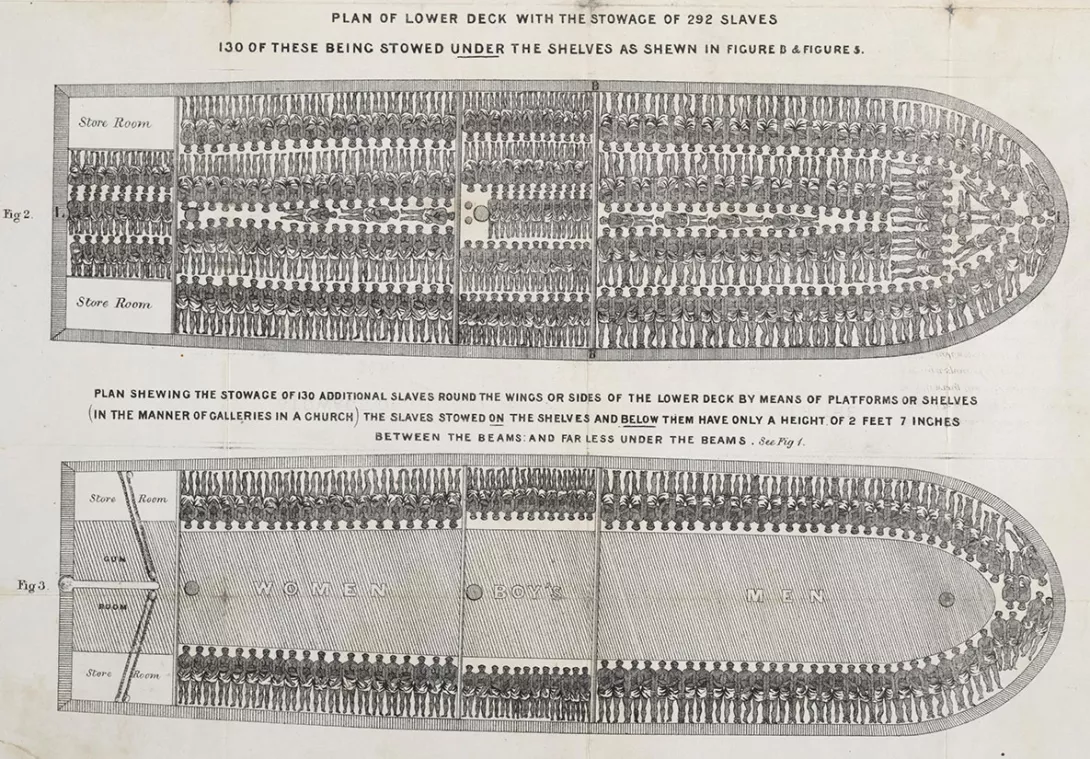

As Dr Helen Paul, one of the historical advisers to the research team, wrote: “The South Sea Company was formed as an integral part of the early modern British state. It was designed from the outset as a slaving company. It shipped enslaved human beings across the Atlantic in terrible conditions.