VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

Labour’s public-private plans are just a return to the dreaded PFI era

SOLOMON HUGHES warns Reeves’s proposed national wealth fund hands City financiers control over billions in public money for big business — and we get... to pay!

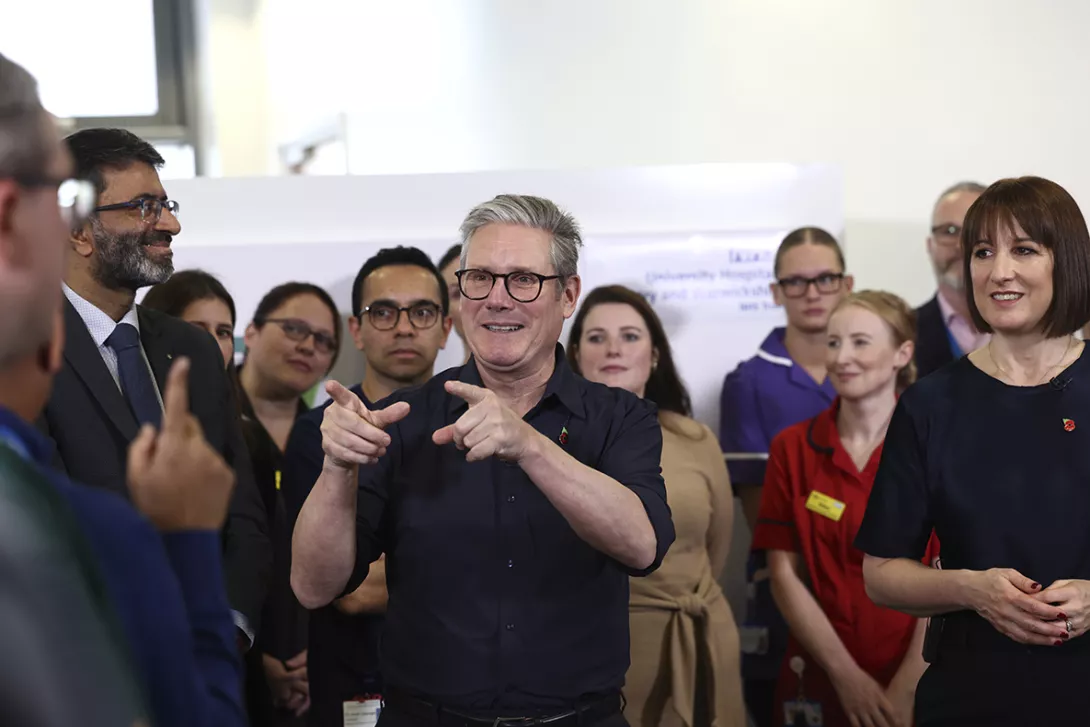

HOW will Keir Starmer’s Labour try to “grow the economy?” The short answer is it is going to try to use public money to persuade international investors to put cash into “growth” industries.

It’s the return of the public-private partnership. The big danger is that, like Labour’s last public-private partnership, the private corporations will get all the growth, while the public sector gets ripped off.

The main economy-grower Starmer is promoting is Rachel Reeves’s proposed national wealth fund. It will invest in key industries like “green energy” and other modern manufacturing sectors.

More from this author

SOLOMON HUGHES probes the finances of a phoney ‘charity’ pushing the free schools and academies agenda

What’s behind the sudden wave of centrist ‘understanding’ about the real nature of Starmerism and its deep unpopularity? SOLOMON HUGHES reckons he knows the reasons for this apparent epiphany

They’re the problem it’s them: SOLOMON HUGHES on the freeloading flunkies of the Labour Party hoovering up VIP tickets to musical and sporting events

SOLOMON HUGHES examines how Labour has gone from blaming Tory deregulation for our economic woes to betting the nation's future on more of it

Similar stories

SOLOMON HUGHES reveals how one of the organisations shaping Labour’s investment plans was created by Tories and bankers, looking like a slightly green-flecked PFI vehicle instead of a body for proper investment