VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

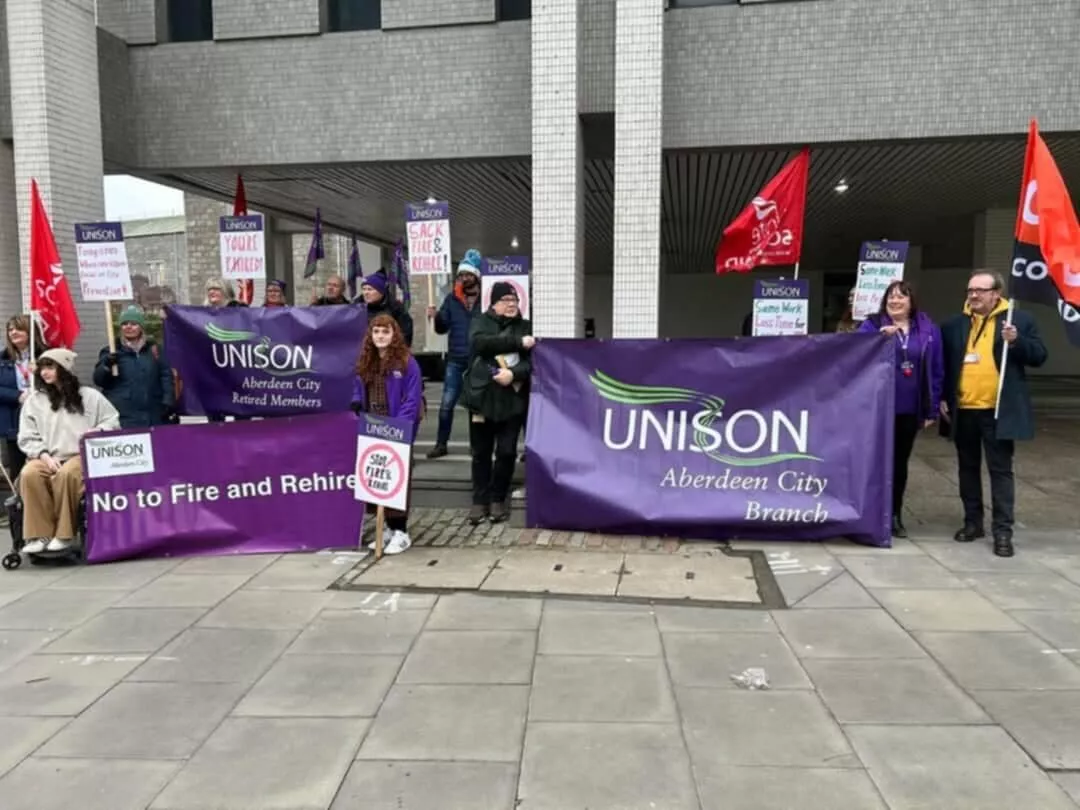

Public ownership matters

Genuine public control of essential services and a democratic renewal are worth fighting for, argues MATT KERR

THIS week saw the fourth anniversary of lockdown. Rightly, these moments will take people back to the countless thousands who lost their lives while one government partied and another took stock of the constitutional possibilities.

They should also bring to mind the millions of workers providing essential services even during its worst phases, often sent into work in the hospital, the supermarket or out emptying our bins pitifully ill-equipped by employers — public and private — chronically ill-prepared for the scenario.

There were moments of desperately needed light relief though, little moments to fend off the sense of doom that seemed to envelop the country and what felt like most of the world.

More from this author

Similar stories

As college workers return to picket lines across the country they’re fighting for more than just a decent wage, or even their jobs, writes MATT KERR