IT is no surprise that so many big business leaders have come out in support of the Labour Party.

It reflects two things. One is the banal fact that Labour looks like winning, and it does corporate leaders no harm at all to be able to say “I backed you at the election” when sitting down opposite ministers in a couple of months’ time to beg for assistance of one sort or another.

Next to a discreet indication that a lucrative boardroom seat will always be waiting for the politician opposite when they tire of parliamentary politics, it is the most potent way to ensure that your special pleadings do not go unheard.

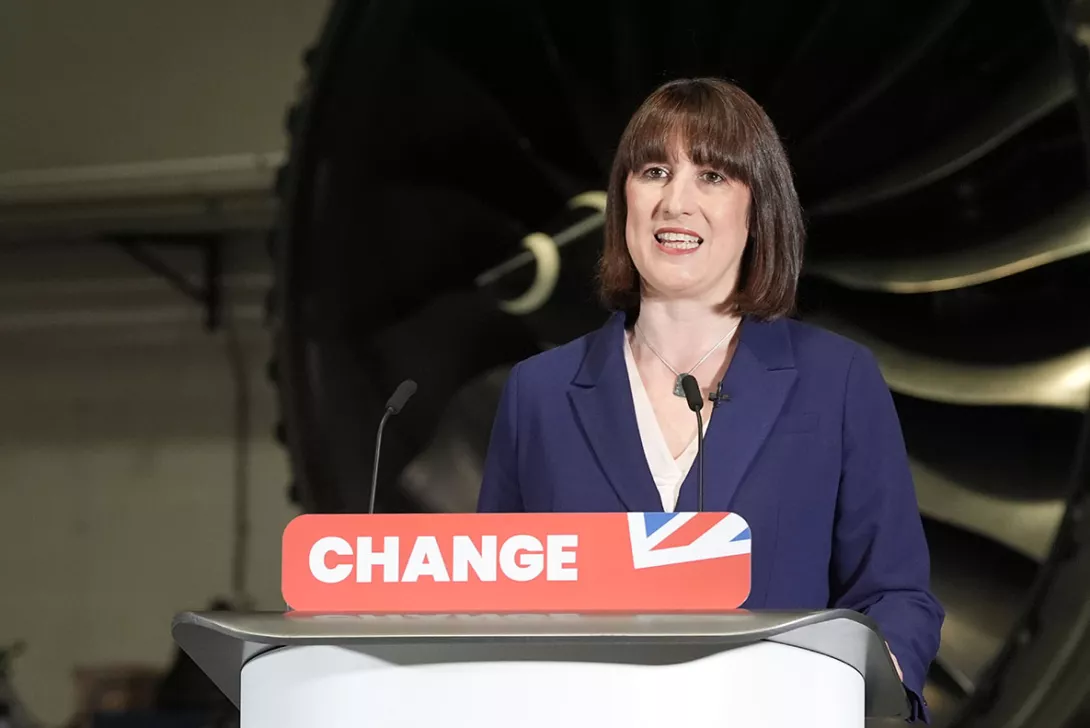

But the larger issue is the second one. Keir Starmer and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves have bent over backwards to place themselves in the service of monopoly capitalism.

That has been reflected in their rhetoric, pledging the “most business-friendly government” in British history, which is a very high hurdle, but is a clear indication of their aspiration.

Sometimes this is extended by a commitment to be “pro-worker and pro-business” as if there were never a conflict between the two.

In fact, Starmer and Reeves know full well there is — that is why they have been busy watering down their commitments on workers’ rights to suit the bosses.

There will be no fire-and-rehire on inferior terms and conditions — unless the employer says it is essential. Zero-hours contracts will be out — unless the boss “convinces” the employee that she or he really wants one.

As Unite’s Sharon Graham says, Labour’s New Deal for Working People now “has more holes than a Swiss cheese.” One can only hope that unions will be able to plug some of those gaps in Labour’s manifesto negotiations.

But the pro-capitalist turn goes much wider than safeguarding the bosses’ sacred right to exploit labour. It has permeated all aspects of the Starmer-Reeves approach.

The 120 signatories to the Labour-backing letter will have noticed that their corporation tax rate is not going to rise under Reeves.

They will have noticed that there is to be no wealth tax — of the kind Starmer once promised — under the impending Labour dispensation.

They will have noticed that outside a railway sector already under semi-control by the state, there is to be no extension of public ownership.

And they have noticed that despite the campaign slogan of “change” in fact Labour is offering nothing of the sort, but rather “economic stability.” That might have marked a point of divergence from the excitable Liz Truss but it hardly differs from Rishi Sunak, whose election boast is that he has restored — economic stability.

However, the 120 capitalists also claim to have noticed something no-one else has. That is Labour’s plan for economic growth.

Never has something so insubstantial borne so much political weight. Since the junking of the £28 billion-a-year green investment plan, Labour’s growth strategy amounts to nothing more than loosening a few planning regulations.

It would throw the miracle of the loaves and fishes into the shade if such a puny measure were to lead the British bourgeoisie to break its preference for global speculation over domestic investment and do what it has not done for a generation now: generate serious growth.

Yet absent tax increases, Starmer and Reeves have no other way to improve public services, making the pledge of “no return to austerity” ring hollow.

The letter from the 120 is another warning sign. The next Labour government will be in the capitalists’ pocket. Only a mass movement of struggle could extract it.