THE financial crisis engulfing local government in Britain is a matter of urgent concern for workers, residents, and policymakers alike. Thousands of council workers face redundancy across the country today and many thousands more citizens live in anxiety as they face the prospect of care home closures and service cuts to the most vulnerable. Our country is suffering from a wound inflicted by its own government.

As the two main parties race ahead in their campaigns to win the general election on July 4, they are both basing their economic appeals on not raising taxes or even cutting them. But neither wants to address the elephant in the room: the catastrophic pressures on public services and the impact on communities.

In 2018, Northamptonshire County Council became the first council since Hackney in 2000 to issue a so-called “bankruptcy” Section 114 notice declaring they could no longer meet their bills. Croydon, Slough, Nottingham City, Northumberland, Thurrock, Woking and Birmingham City have since followed.

We are seeing an unravelling of the state infrastructure and the supporting agencies that have worked with it to build our communities.

In Derbyshire last month, the county council voted to close 10 of the 22 remaining Sure Start Centres. Back in 2017, it had 64 such centres and the reduction to 22 had already seen the numbers of children in care rise by 41 per cent. Continuing to cut these services can only inevitably lead to more people in care, in police stations, and hospitals.

Now Derbyshire is “consulting” with the public on closing 11 care homes and eight day centres for the elderly. They’re also “consulting” on the end of discretionary grant funding. Not a cut — the actual end of all funding to voluntary and community groups across the county.

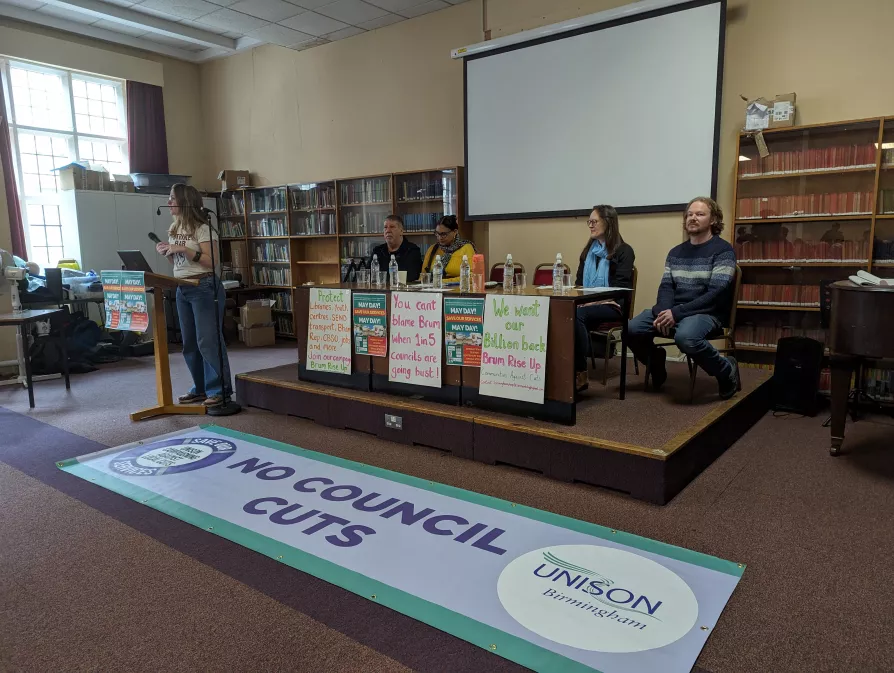

Over in the West Midlands, Birmingham City Council faces a similar devastation. £24 million to be sliced off adult social care alone. Community safety, local environment, and highway maintenance will all suffer greatly to plug the funding gap.

This comes against a national backdrop where one in 10 local government workers are reliant on in-work benefits, underscoring the severe strain on the sector. Their pay has decreased also since 2010. A 25 per cent cut that, combined with the recent cost-of-living crisis, has left so many desperate and even some accepting redundancy just to pay the bills on the doormat.

Public services are deeply wounded and this is a truth that everyone in Britain can see for themselves. The closure of community centres, libraries, and day centres for the elderly among many other services has been going on for over a decade now. According to the National Audit Office, total spending power for local authorities fell by 26 per cent between 2010-11 and 2020-21. Some services have faced real-terms cuts of 40 per cent.

The Local Government Association representing councils has issued a stark warning that the current government funding model is fundamentally broken. They say nearly one in five councils are close to issuing a Section 114 Notice and an extra £4 billion is needed over the next two years just to maintain current services.

The underlying problem of the huge strain on services is the ideological hostility of this government to the welfare state.

Since 2009, the collective wealth of the top 10 billionaires in Britain has grown from £47.77bn to over £182bn. Has your pay packet grown by 281 per cent since 2009? But then, with a government of millionaires headed by a Prime Minister worth £730m in his own right, why would this be so surprising?

Locally, what we can see close up though is also further ideologically driven problems of chronic underinvestment in local services and the increasing privatisation of public-sector work.

For ordinary people, it doesn’t matter which of the big two is in control locally, the central funding isn’t there. And what funding there is, often gets squandered on contracts that produce huge profits for shareholders.

What of the labour movement’s response to this? Some say we should be seeing clear blue water between the Labour Party’s position and the government. Instead, the shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has ruled out the bailout of councils in trouble.

The Labour manifesto unveiled last Thursday morning did show some promise. An end to the ridiculous obsession with competitive bidding between councils for money and also a return to multi-year settlements to provide stability.

But no-one should be under any illusions. Tinkering around the edges will not save local services or communities. To heal this wound that the government have inflicted on our society, we need progressive taxation that addresses wealth inequality and provides adequate funding.