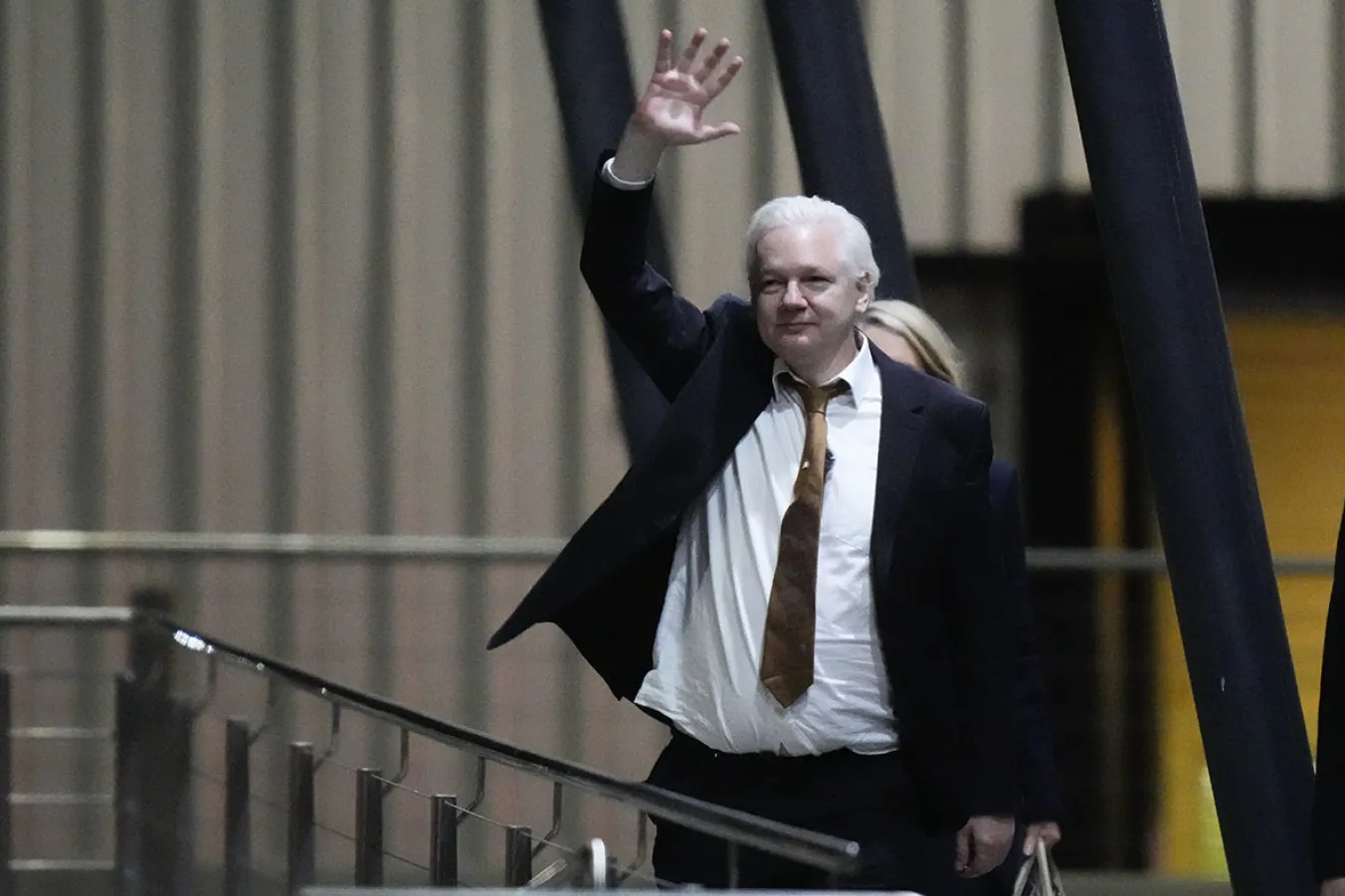

Julian Assange lands in Australia a free man

Stella Assange warns case sets dangerous precedent for press freedom

JULIAN ASSANGE landed in Australia a free man today after a 14-year battle against extradition to the US.

The WikiLeaks founder flew into Canberra after pleading guilty to a single charge under the Espionage Act for publishing evidence of US war crimes as part of a deal with US authorities.

The use of the 100-year-old law, originally used to prosecute spies during WWI, was condemned as having grave implications for press freedom.

More from this author

Similar stories

At long last the WikiLeaks founder is free. For all those who care about freedom of speech it’s time to celebrate, writes TIM DAWSON of the International Federation of Journalists