I GREW up in Harston, five miles south of central Cambridge down the A10. A little tranquil village with a population of less than 2,000 with meadows, a school, village hall, pub, petrol station and post office-cum-store. And a village in an affluent part of Britain that has both a Porsche centre and a Ducati motorbike shop.

Harston has a gross disposable household income of £27,031 — compared to a national average of £20,425. The village is part of South Cambridgeshire, a constituency that in 2019 elected Conservative Anthony Browne to Parliament — who voted with his party in the House on all but one occasion out of 982 — and that has for many years been a Tory stronghold.

A constituency with low unemployment levels and relatively high levels of education, health and income levels that has been named one of the best places to live in Britain several times. And a constituency where the average house price is £429,000 — a lot more than the national average of £286,000.

In the general election on July 4, the voters of South Cambridgeshire (where the constituency boundaries were changed under a recent Boundary Commission review) nevertheless firmly rejected the Tories, who lost by over 10,000 votes to the Liberal Democrats.

A pattern that was seen across the country, where several Cabinet ministers and other Tory “big beasts” lost their seats — including former prime minister Liz Truss.

In 1997 the Conservatives had what was at the time their worst election result in well over 100 years in a general election, after ruling for nearly 18 years, gaining 30.7 per cent of the vote and 165 seats. In the last two elections — and during the Thatcher years as well as in the 1950s and ’60s — the party got over 40 per cent of the vote. In 2024 they won only 23 per cent of the vote and 121 seats — the Conservative Party’s worst result ever.

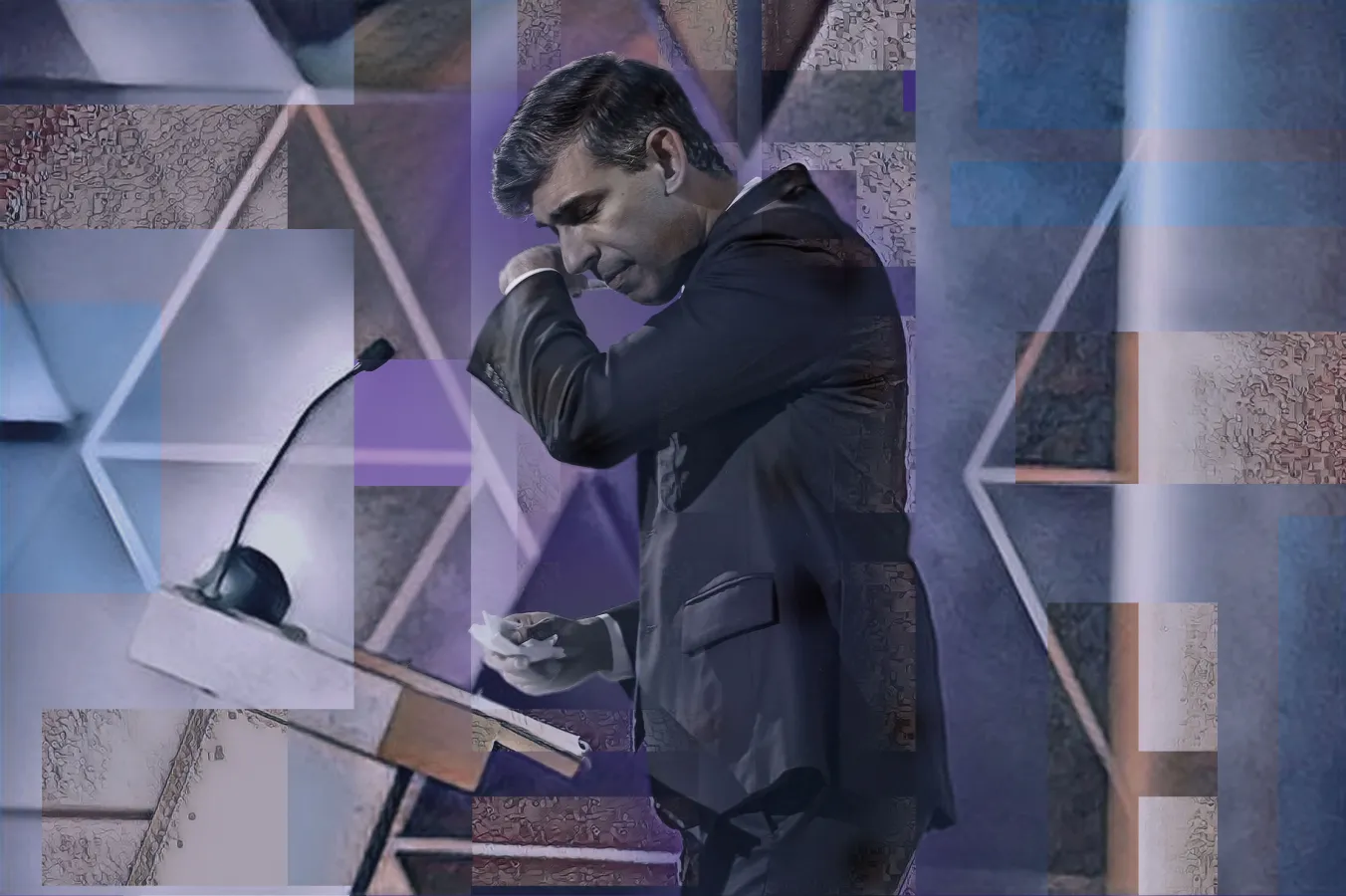

“The British people have delivered a sobering verdict tonight,” outgoing PM Rishi Sunak said after winning his seat on Friday morning. Later that morning he stepped out of 10 Downing Street, said “I am sorry,” and added he was stepping down as party leader.

Deprivation all round

“We all know how bad things are: massive debt, social breakdown, political disenchantment. But what I want to talk about today is how good things could be,” David Cameron said in his conference speech in 2009, the year before he became PM.

But the electorate has had it increasingly hard during the last 14 years of Tory rule, with a Brexit that split the country and a chaotic last five years that has seen four Tory prime ministers — including nearly 50 disastrous days of Liz Truss and her mini-Budget — and five Chancellors of the Exchequer.

“By 2024, Britain’s standing in the world was lower, the union was less strong, the country less equal, the population less well protected, growth more sluggish with the outlook poor, public services underperforming and largely unreformed,” one can read in a new collection of essays edited by prominent historian Anthony Seldon and political writer Tom Egerton, The Conservative Effect 2010-2024: 14 Wasted Years?

“Overall, it is hard to find a comparable period in history of a Conservative, or other, government which achieved so little, or which left the country at its conclusion in a more troubling state,” the analysis concludes.

The Institute for Government, an independent think tank, says in a new report that most services are performing “substantially worse” than in 2010 when the Conservatives took office and that the new government will face public services on the brink of collapse. New income statistics from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), an independent economics research institute, suggest this Parliament is on course to be the worst for living standards on record.

“The rise in material deprivation is seen across every age group, housing tenure, work status, household composition and region,” the IFS concludes in its report, “Living standards since the last election,” published in March.

According to a report from the House of Commons Library on food poverty from August, 4.7 million people in Britain were experiencing food poverty in 2021-22, 2.1 million people in Britain had lived in a household which had used a foodbank in the previous 12 months, and foodbanks are used by an estimated 3 per cent of British families.

The number of people in “food insecure” households rose to over 7 million in 2022-23, an increase of 2.5 million people since 2021-22. And according to the Food Foundation tracker, 15 per cent of households in Britain experienced food insecurity in January.

Even in South Cambridgeshire, there are foodbanks and food hubs open to residents who need to access low or no-cost food — including one on Chapel Lane in Harston, less than half a mile from where I grew up. And if you look beyond its world-famous colleges, prosperous Cambridge has been ranked Britain’s most unequal city on several occasions.

It is also a city where child poverty and homelessness are on the rise and many households in Cambridge are struggling to heat their homes. “Poverty remains a significant issue in Cambridge,” one can read in Cambridge City Council’s most recent anti-poverty strategy. Cambridge City Foodbank gave 15,914 three-day emergency food parcels to people in need during 2023.

So, what does Britain’s electorate — including people in Cambridgeshire — have to look forward to with the new Labour government? Well, that is a difficult question to answer if we are to go by Starmer’s time as leader and Labour’s election campaign.

Peter Kenworthy’s analysis of the general election continues tomorrow.