THE turnout at last week’s election was just over 60 per cent, compared to 67 per cent in 2019.

The latest British Social Attitudes report, published in June by the National Centre for Social Research, reveals that 79 per cent of those polled say the system of governing Britain could be improved “quite a lot” or “a great deal.”

And perhaps the real problem with British politics has to do with the first past-the-post-system where large parts of the electorate are not (comparatively and sufficiently) represented in the British Parliament.

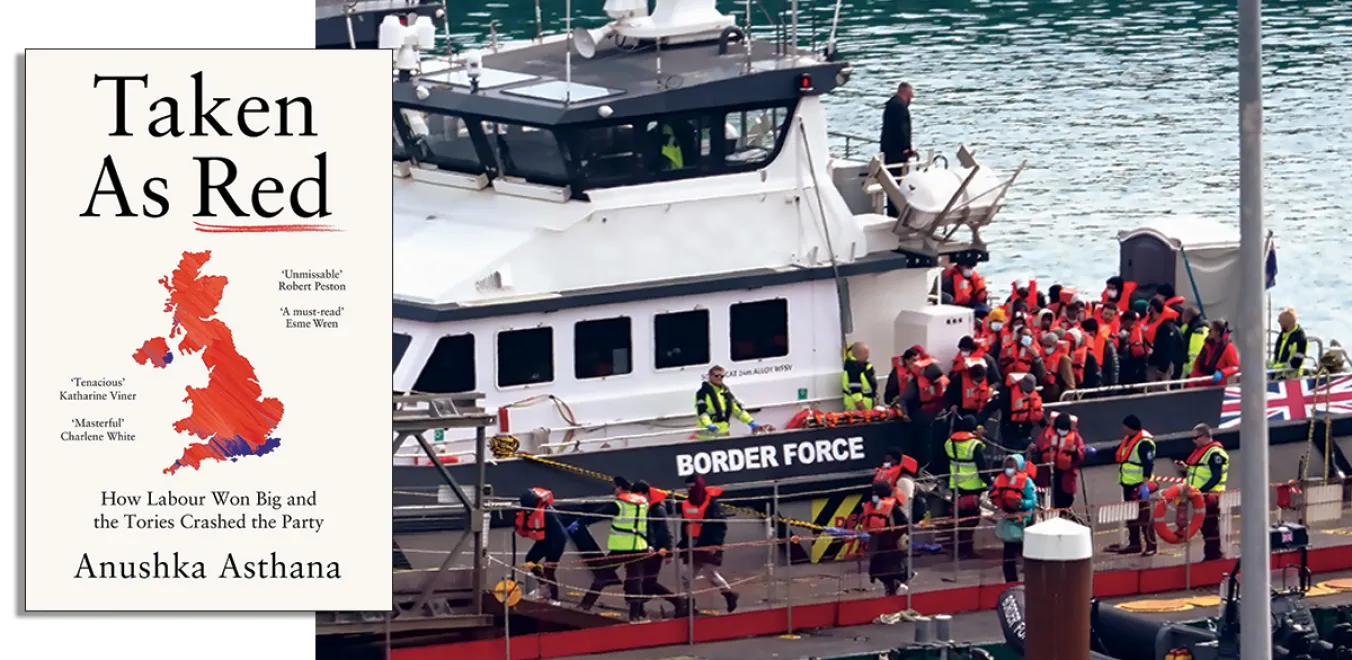

This is a system where Labour and the Conservatives have a virtual monopoly on power and left-of-centre and right-of-centre politics — even though both parties have dwindling memberships (Labour has lost 200,000 members since the last election when Corbyn was leader) and the Conservatives have implemented an increasingly right-wing and populist set of policies that include Brexit, ditching green policies and a Bill that aims at sending asylum-seekers to Rwanda.

A system that would seem to exclude any real possibility of fundamental change, one way or the other, where more than 20 per cent of the electorate voted for the Greens and Reform UK, who only got a total of nine seats in the 650-member parliament.

Starmer’s Labour’s 33 per cent of the vote and less than 10 million votes secured 412 seats in 2024 and a majority of more than 170, while Corbyn’s Labour in 2017 only got 262 seats from 40 per cent of the vote and more the 12 million votes as well as 202 seats from 32 per cent and over 10 million votes in 2019.

The first past-the-post-system is also a system where tactical campaigning and tactical voting often forces people to vote for the least worst option.

“We deserve better than a Labour Party that is offering more of the same. Angela [Rayner, Labour Deputy Leader] says that Keir has changed the Labour Party and she’s right — he’s changed them into the Conservatives,” Carla Denyer, the Green Party leader, said in a BBC election debate.

Power as an end?

Sunak announced the election in pouring rain, and when Starmer met the king at Buckingham Palace, the umbrellas outside were also abundant. A rather fitting metaphor for the state of the country and British politics.

Soon after the sun came out. And when the new Prime Minister stood outside the door at number 10 Downing Street, Starmer said that Britain needs a reset and that the work of change will begin immediately. “My government will fight until you believe again,” he added.

And I hope that the politicians that have been elected to the new parliament will look to change Britain, including dealing with child poverty, homelessness and foodbanks in the area where I grew up and countrywide. As well as climate change and the many other pressing issues in the country today. But I am not hopeful — and I am not alone in this.

Politicians are the least-trusted profession in Britain — below advertising executives, journalists and estate agents. And trust in British politicians is at an all-time low, since Ipsos surveys began in 1983. Just 9 per cent of the British public trusted politicians to tell the truth in December, down from 22 per cent in 2022 and 23 per cent in 1999.

The new British Social Attitudes report reveals that the public is more critical now of how Britain is governed than ever. Nearly half say they “almost never” trust governments of any party to place the needs of the nation above the interests of their own political party — 22 points above the figure from 2020. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, the number was well below 20 per cent.

And a YouGov poll from late June showed that most Britons think that parties go back on their manifesto promises and that they tend to see both the Conservatives’ and Labour’s election promises as unaffordable and unrealistic.

For true change to happen, we will need a generation of politicians more willing to be consistently truthful, lead, be visionary, shape public opinion, and not just focus on the importance of being electable and elected by reacting to polls and political currents. For to truly change something, to make an impact, you need to challenge and change opinions, not merely secure votes.

Starmer — and many modern politicians — on the other hand would seem to represent what inner-party-member O’Brien says to Winston Smith in George Orwell’s 1984 in the Ministry of Truth: “The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power [ … ] Power is not a means; it is an end.”

Margaret Thatcher was once asked what her greatest achievement was. She replied, “Tony Blair and New Labour.” Keir Starmer (and his cautious “Ming vase manifesto,” as it was called by a former New Labour aide) could in turn be the greatest achievement of the collective efforts of Cameron, May, Johnson, Truss and Sunak.