From London’s holly-sellers to Engels’s flaming Christmas centrepiece, the plum pudding was more than festive fare in Victorian Britain, says KEITH FLETT

DYLAN MURPHY looks back to when mass resistance led by the Communist Party of Great Britain broke the back of British fascism in 1934

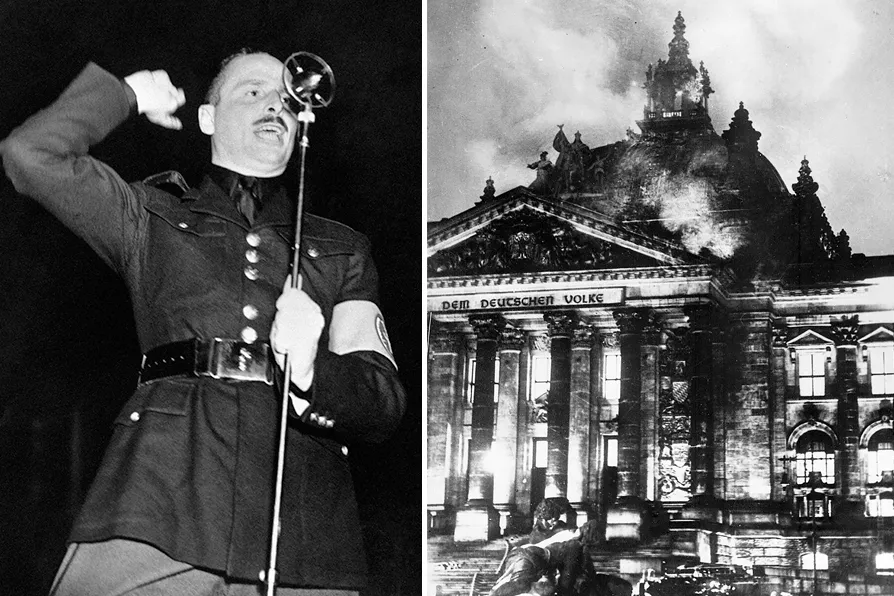

(Right) The Reichstag burns on February 27 1933. Walter Gempp, head of the Berlin fire department was dismissed on March 25 for presenting evidence that suggested Nazi involvement in the fire - he was strangled in prison on May 2 1939; (left) Sir Oswald M

(Right) The Reichstag burns on February 27 1933. Walter Gempp, head of the Berlin fire department was dismissed on March 25 for presenting evidence that suggested Nazi involvement in the fire - he was strangled in prison on May 2 1939; (left) Sir Oswald M

DURING 1933 and 1934, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) made a concerted effort to establish itself as a mass political party, mirroring the rise of fascist movements across Europe.

However, this aspiration was decisively thwarted by a powerful anti-fascist movement that emerged from the grassroots. This popular resistance played a crucial role in preventing the BUF from gaining the widespread support it sought.

Hitler’s ascent to power on January 30 1933, led to him swiftly implemented his totalitarian agenda, crushing the organised working class. The infamous Reichstag fire, falsely attributed to the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), served as a pretext to ban the party and imprison an estimated 100,000 members in concentration camps.

By July 1933, Germany had become a totalitarian dictatorship. Trade unions and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) were banned, the workers’ press shut down. Hundreds of thousands of communists, trade unionists and socialists were incarcerated, forced into hiding or had fled the country.

The dramatic events unfolding in Germany were not lost on the ruling class of Britain. They observed with keen interest the swift and brutal suppression of the German labour movement by the Nazi regime. This presented the British capitalist class with a profound dilemma, one that mirrored the challenges faced by their German counterparts. How could they restore the profitability and competitiveness of their industries and the broader economy when the British working class was so exceptionally well-organised?

The ascent of Adolf Hitler to power in Germany sent shock waves through the British labour movement. A central question reverberated throughout the movement: how could fascism triumph in a nation that boasted the most powerful labour movement in Europe?

Horrified by the destruction of the German labour movement the CPGB rank and file led a mass movement from below which actively confronted the BUF on the streets, engaging in direct action and counter-demonstrations. This grassroots movement, involving many activists who had fought in World War I, has been overlooked by previous historians and played a crucial role in resisting the fascists.

Despite its initially small size, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) experienced a period of rapid growth, expanding to over 50,000 members by the middle of 1934. This surge in membership was significantly bolstered by support from capitalist interests, both domestic capitalists, senior military figures and fascist governments in Europe.

A crucial element of this support came in the form of direct funding. The BUF received a considerable sum of £60,000 from the Italian fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, demonstrating a clear financial link between European fascist regimes and their British counterparts. In addition to foreign funding, the BUF also enjoyed the public backing of influential figures within the British Establishment. Lord Rothermere, the owner of the Daily Mail, was a particularly vocal and powerful supporter. His endorsement provided the BUF with a level of legitimacy and media exposure that it would have otherwise struggled to achieve.

This open support from a segment of the capitalist class revealed a chilling reality. It demonstrated that there were powerful elements within the ruling class who were considering the option of dismantling the organised labour movement if parliamentary democracy proved incapable of maintaining social stability in Britain.

The Daily Mail, Evening News and the Sunday Dispatch actively promoted the BUF, providing it with extensive publicity. This media campaign was instrumental in fuelling the BUF’s growth, particularly in a context of mass unemployment and widespread poverty, where its populist and nationalist message found a receptive audience.

Drawing direct inspiration from the successes of fascist movements in Germany and Italy, Oswald Mosley, the leader of the BUF, adopted similar tactics for the British context. The BUF embarked on a campaign of public visibility, organising numerous rallies and public meetings across the nation. Mosley used these platforms to disseminate his ideology and recruit new members.

A particularly provocative tactic involved organising marches through predominantly Jewish areas, especially in London’s East End. These marches were designed to incite fear and division.

Emulating Hitler’s Brownshirts, the BUF engaged in direct physical attacks on Jewish communities and labour movement activists. These acts of violence were often carried out with a disturbing degree of police complicity.

By the spring of 1934, buoyed by the successes of fascist regimes in Europe and the high-profile support he had garnered, Mosley became convinced that the BUF was on the cusp of transforming into a genuine mass party. This support fuelled a recruitment drive throughout the spring and summer. The results were dramatic: membership surged from an estimated 17,000 in February to over 50,000 by July 1934. This period marked a peak in the membership of the BUF.

Popular opposition to the BUF surged in 1934, led by the organised working class. One anti-fascist of this period observed: “The British working class gave the Blackshirts their answer. Every demonstration called by the fascists was answered by a greater counter-demonstration of workers and anti-fascists.”

Local media reports, including those in the Daily Worker, give us an insight into this mass movement from below. They provide numerous reports on disrupted BUF meetings across Britain during 1934, with fascists unable to hold meetings in “Red” Glasgow and forced to abandon events in places like Dumfries retreating under police escort in Ipswich.

In May 1934, over 2,000 workers opposed a BUF meeting in Greenwich. They drowned out the BUF speaker, chanting slogans such as “No blackshirts in Greenwich.”

John Beckett of the BUF faced 10,000 anti-fascists in Gateshead and 5,000 in Newcastle during a Tyneside tour. In Newcastle he was pushed off the platform as the meeting broke up in pandemonium. Mounted police were used to clear a path for Beckett’s retreat from the meeting.

Mosley’s Albert Hall recruitment meeting in April 1934, was met by determined resistance involving hundreds of CP members and thousands who counter-demonstrated outside the Albert Hall.

When the BUF announced another mass rally for June 7 at Olympia, the CPGB leadership made the public call for a mass mobilisation against the BUF’s planned event inviting all labour movement organisations to participate in this activity. The CPGB’s campaign against Mosley’s Olympia Rally quickly gathered significant momentum. A major breakthrough came when the party secured the official support of the Engineers’ Union, which called on its members to support the counter-demonstration.

Provincial campaigns against the BUF also continued with undiminished intensity. On June 1, BUF meetings in both Bristol and Edinburgh were met with large and determined counter-demonstrations. At the Bristol meeting the BUF speaker was hurled from the platform and the meeting ended in chaos.

In Edinburgh despite the presence of mounted police, the anti-fascist protestors broke through police lines to the buses waiting to take the fascists away. They attacked the fascists on the buses, causing great damage to the vehicles and hospitalising many fascists in the process.

The Daily Worker commented: “The organised thugs, rushing around the country in armoured cars and buses, received another good thrashing on Friday night.”

The Olympia rally itself proved to be a pivotal moment. The brutal violence meted out by BUF stewards against anti-fascist hecklers inside the venue was widely reported and led to a wave of public revulsion. This incident severely undermined the BUF’s attempts to present itself as a respectable political organisation and alienated many of its supporters.

The aftermath of the Olympia rally was catastrophic for the BUF. Its membership, which had peaked at 50,000 in June 1934, plummeted to a mere 5,000 by October of the same year. This dramatic decline was a direct consequence of the intense and unrelenting opposition it had faced from the anti-fascist movement.

The sustained pressure from the anti-fascist movement forced Mosley to begin cancelling meetings, a fact he himself admitted in a letter to the home secretary in late June 1934. This was a clear indication of the BUF’s waning confidence and organisational capacity.

The CPGB’s summer campaign reached its zenith with a massive rally in Hyde Park on September 9 1934. Over 100,000 anti-fascists gathered to oppose Mosley, a powerful demonstration of the strength of the anti-fascist movement. This event decisively dented the BUF’s confidence and precipitated a period of decline that lasted until 1936.

The mass anti-fascist movement that emerged from below was the crucial factor in undermining the BUF’s ambitions. It demonstrated the power of grassroots activism and direct action in confronting and defeating the fascist threat. The united actions of the workers led by the CPGB, demonstrated a fundamental lesson for the modern day: only vigorous counter-action hinders the growth of the menace of fascism.

Dylan Murphy is a labour movement historian who has researched the struggle against fascism for his doctorate.