Does widespread and uncontrolled use of AI change our relationship with scientific meaning? Or with each other? ask ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

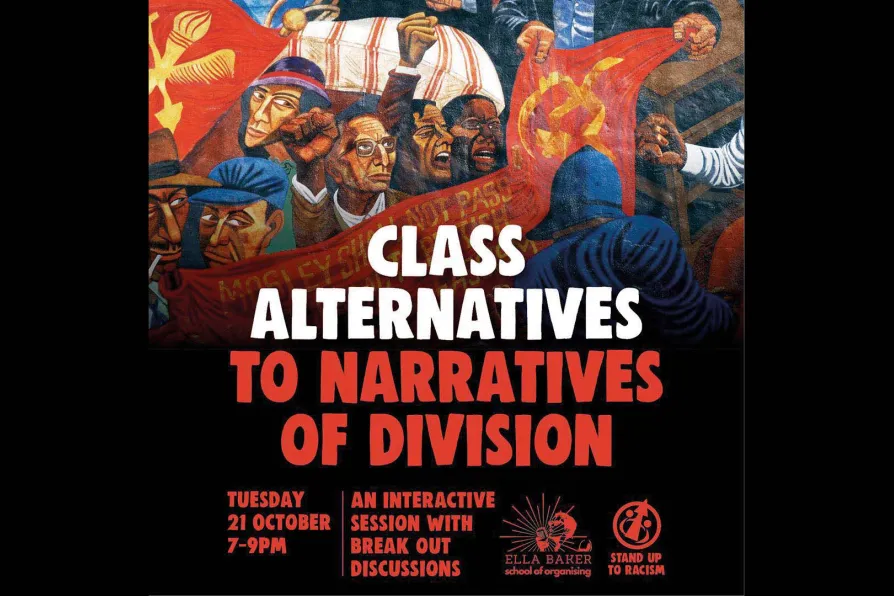

KEVIN COURTNEY of Stand Up to Racism and JOHN PAGE of the Ella Baker School of Organising announce a joint project aiming to unite trade unions and social movements in creating new narratives to fight the divisive rhetoric of the far right

ON TUESDAY October 21 2025, Stand Up To Racism and the Ella Baker School of Organising will host an online session titled Class Alternatives to Narratives of Division. This event aims to confront the rising tide of far-right extremism through political education and collective action.

Stand Up To Racism is also proposing to others a new alliance to combat the far right, seeking the widest possible involvement from trade unions and social movements to rebuild class solidarity and challenge divisive narratives.

Talk to any shop steward or community activist today, and one question surfaces repeatedly: “How did we get here?” Over the past 18 months, Britain has witnessed the most widespread racist rioting since 1919, the largest far-right march in its history, and polls showing Reform UK’s support rivalling that of Labour and the Conservatives combined.

Private trade union polling reveals that even union members are not immune to the drift toward the authoritarian right. So, how did we arrive at this point, and more crucially, what do we do next?

To understand our current predicament, we must look back. In 1976, the Grunwick dispute marked a turning point. Led by racialised minority and migrant women workers, it was the first strike of its kind to gain widespread support from the broader labour movement.

At its peak, Arthur Scargill brought thousands of National Union of Mineworkers members to join mass pickets. On the picket line, shop stewards from industries like printing and postal services declared they would not stand by as police attacked striking women or broke their lines. This was class solidarity in action.

Around the same time, Micky Fenn, a leader of the unofficial National Port Shop Stewards Committee, famously said: “I will always have more in common with a docker from India than I will ever have with an investment banker from Britain.”

This era represented a high point of class consciousness, when trade unionists led their members in secondary action to support other workers, embodying the principle that an injury to one is an injury to all. At the time, working-class politics and trade unionism were inseparable. But much has changed since then.

The right seized on economic shifts to launch a relentless assault on the working class. The introduction of containerisation on the docks, for instance, was used not to benefit workers but to undermine their unions’ strength. The 1984–85 miners’ strike, particularly the ambush at Orgreave, marked the peak of this physical and ideological offensive.

The so-called gig economy, rising child poverty, unaffordable housing, the cost-of-living crisis, and soaring inequality are not accidents but the intended outcomes of neoliberal policies. If the share of national income going to wages today matched 1979 levels, the average worker’s annual salary would be £10,000 higher. That wealth has instead enriched the already super-rich, fuelling widespread anger.

In 1979, half of British workers were unionised; today, just over one-fifth are. Too often, trade unions have retreated from providing political education, leaving no positive outlet for this anger. Into this vacuum step far-right charlatans who claim to represent the “white working class” by scapegoating minorities.

Unlike in the past, when far-right groups might march through communities and disperse, they are now, alarmingly, seeking to establish roots in working-class areas. Learning from global far-right movements, they aim to entrench themselves locally.

Meanwhile, the Labour Party, rather than championing the working class in all its diversity, has increasingly adopted racist rhetoric and policies in response to rising domestic prejudice. This is how we got here.

So, how do we move forward to counter the racism threatening to dominate the debate ahead of the predicted May 2029 general election? History offers clues, though not blueprints. In 1936, community organising around housing in Stepney — led by the Communist Party and elements of the Catholic Church — created a unifying “story of us” that mobilised thousands to stop Oswald Mosley’s fascists at Cable Street.

Reflecting later, communist organiser Phil Piratin asked: “How was Mosley able to recruit Stepney workers? … If they saw in the fascists the answer to their problems, why? What were the problems? … Was there more that ought to be done?”

These questions remain critical today. The October 21 session will kickstart a reappraisal of how to meet the challenges posed by this old and deadly foe. Narratives of division are the Achilles’ heel of the labour movement. With just 43 months until the next election, we must act swiftly to change history’s course.

Stand Up To Racism’s proposed new alliance aims to unite trade unions and movements in this fight, fostering the solidarity needed to prevent a Trump-like government from eroding the rights and freedoms won over decades. Join the session to help shape this urgent response.

Sign up at www.bit.ly/SUTR2025.

Once again Tower Hamlets is being targeted by anti-Islam campaigners, this time a revamped and radicalised version of Ukip — the far-right event is now banned by the police, but we’ll be assembling this Saturday to make sure they stay away, says JAYDEE SEAFORTH

Labour’s watered-down legislation won’t protect us from unfair dismissal or ban some zero-hours contracts until 2027 — leaving millions of young people vulnerable to the populist right’s appeal, warns TUC young workers chair FRASER MCGUIRE