As women dominate public services yet face pay gaps, unsafe workloads and rising misogyny, this International Women’s Day and TUC Women’s Conference must be a rallying point, says ANDREA EGAN

The charter emerged from a profoundly democratic process where people across South Africa answered ‘What kind of country do we want?’ — but imperial backlash and neoliberal compromise deferred its deepest transformations, argues RONNIE KASRILS

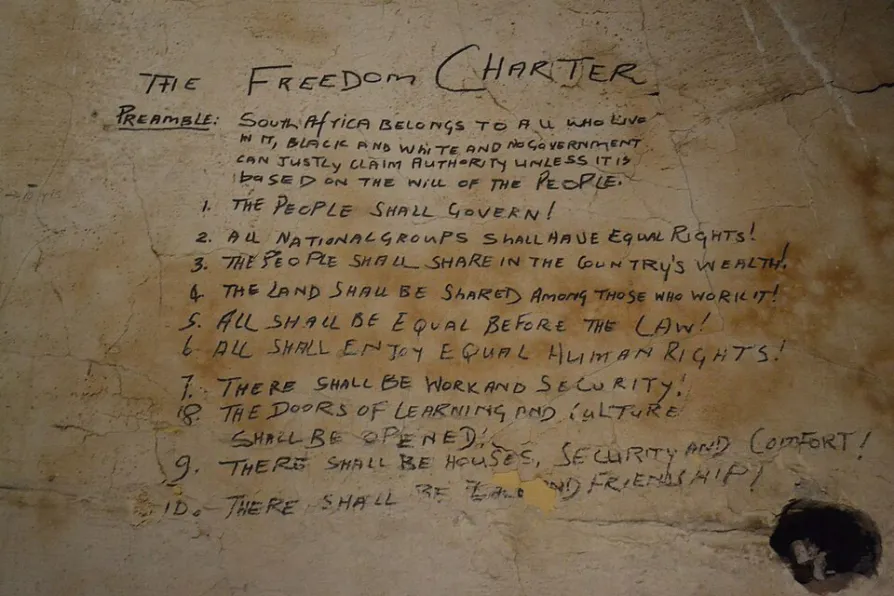

HISTORIC DREAM UNFULFILLED: The Freedom Charter seen here written on the wall of a cell in the Palace of Justice in Pretoria during the 1964 Rivonia Trial, where Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment. Photo: Creative Commons — PHParsons

HISTORIC DREAM UNFULFILLED: The Freedom Charter seen here written on the wall of a cell in the Palace of Justice in Pretoria during the 1964 Rivonia Trial, where Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment. Photo: Creative Commons — PHParsons

THE Freedom Charter was adopted in Kliptown on June 26 1955, 70 years ago. Thousands of delegates travelled from across South Africa — by train, by bus, on foot — to take part in the Congress of the People. They met under an open sky, gathered on a dusty field where a wooden stage had been erected.

Armed police watched from the perimeter, but the atmosphere was determined and jubilant. One by one, the clauses of the charter — on land, work, education, housing, democracy, peace — were read aloud, and each was met with unanimous approval. The charter was the distilled expression of months of discussion and collective vision.

Discussions of the charter seldom place it in its full historical context. Yet to understand its true significance, we must see it as part of a wider global moment — an era in which oppressed peoples across the world were rising against colonialism.

After the defeat of fascism in 1945, there was a deep sense of possibility. The victory fuelled a new international moral order, embodied in the founding of the UN and its charter, with its emphasis on human rights, self-determination, and peace. In the colonised world, this was accompanied by a wave of anti-colonial struggle, with growing demands for independence and equality. India gained independence in 1947. Ghana followed in 1957.

In April 1955, two months before the Freedom Charter was adopted, 29 newly independent and colonised nations met in Bandung, Indonesia. The Bandung Conference gave voice to the aspirations of the global South — to end colonialism and racial domination, assert autonomy in world affairs, and build co-operation among formerly colonised peoples. Bandung thrilled anti-colonial forces around the world. The Freedom Charter emerged amid this excitement. It was a declaration by an oppressed majority that they would not accept colonial domination.

This period of hope was shadowed by a fierce imperial backlash. In Iran, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh’s nationalisation of oil in 1951 was met with a CIA — and MI6-backed coup in 1953. In Guatemala, President Jacobo Arbenz’s land reforms provoked a similar response, and in 1954 the CIA orchestrated his removal.

Across the world, moments of popular sovereignty were crushed to preserve imperial power. The Korean War (1950–53) marked the aggressive militarisation of the cold war. In 1961, Congo’s first elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated with the support of the CIA. In 1966, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown in a Western-backed coup.

In South Africa, the vision set out in the Freedom Charter was swiftly met with state repression. Months after its adoption, 156 leaders of the Congress Alliance were arrested and charged with treason. Then came the Sharpeville Massacre in March 1960. The apartheid regime banned the ANC and the PAC, forcing the liberation movements underground. In response, the ANC took the decision to turn to armed struggle.

The Freedom Charter cannot be separated from the process that gave it life — a process that was profoundly democratic, consultative, and rooted in the daily lives of ordinary people. In 1953, the African National Congress and its partners in the Congress Alliance issued a call for a national dialogue: to ask, plainly and urgently, “What kind of South Africa do we want to live in?”

The response was remarkable. Across the country, in townships, rural villages, workplaces, churches, and gatherings, people came together to develop their demands. Submissions arrived handwritten, typed, or dictated to organisers.

The charter expressed a vision of South Africa grounded in equality, justice, and shared prosperity. “The People Shall Govern” was the opening clause, affirming not only the right to vote but the principle that power must reside with the people. “The Land Shall Be Shared Among Those Who Work It” challenged the dispossession at the heart of colonial and apartheid rule. Crucially, the charter called for an economy based on public benefit rather than private profit: “The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people.”

Education, housing, and healthcare were to be universal and equal. The charter envisioned a South Africa without racism or sexism, where all would be “equal before the law,” with “peace and friendship” pursued abroad.

After the banning of the liberation movements in the 1960s and the brutal repression that followed, the Freedom Charter did not disappear — but it receded from popular memory.

In the 1980s, it surged back into public life with renewed force. The formation of the United Democratic Front in 1983 in Cape Town and the emergence of the Congress of South African Trade Unions in 1985 in Durban gave new organisational life to the charter. Grassroots formations drew on unions, civics, and faith groups to take the charter out of the archives and into the streets. For both the now powerful mass movement, the charter promised a future grounded in radical democracy and a fundamental redistribution of land and wealth.

The charter became a vital reference point for the negotiations that began after the unbanning of the liberation movements in 1990. Its language and principles profoundly shaped elements of the 1996 constitution.

The charter’s insistence that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it” and that “the people shall govern” was carried through into the constitutional affirmation of non-racialism and universal suffrage. Guarantees of equal rights, human dignity, and socio-economic rights such as housing, education, and healthcare echo the charter’s vision.

But the transition involved compromise. In the 1980s, the charter had been a call for deep structural transformation. At the settlement, key clauses — particularly those calling for the redistribution of land and the sharing of national wealth — were softened or deferred.

The final settlement preserved existing patterns of private property and accepted a macroeconomic framework shaped in part by global neoliberal pressures. While the vote was won, the deeper transformations envisioned in the charter were postponed.

The result is that today, 30 years after the end of apartheid, structural inequalities remain. In 1998, Thabo Mbeki described South Africa as a country of “two nations” — one rich and white, the other poor and black. That characterisation remains disturbingly accurate. The charter’s economic promises have not been fulfilled.

The 2024 general election marked a historic turning point. Taken together, the two dominant parties garnered support from less than a quarter of the eligible population. Nearly 60 per cent of eligible voters did not participate at all. This reflects deep disillusionment. The charter’s promise that “the people shall govern” demands more than a vote — it requires sustained participation.

This requires rebuilding mass democratic participation from below. It means rekindling the culture of popular meetings, community mandates, and worker-led initiatives that grounded the charter in lived experience.

It means going beyond elections and restoring a sense of everyday democratic agency — in schools, workplaces, and communities. It means making good on the promise to redistribute land and wealth.

It also means rebuilding solidarity across the global South. The formation of The Hague Group in January this year to build an alliance in support of Palestine was a major breakthrough. The meeting it will hold in Bogota in July promises to expand its reach and power.

But we must recognise the scale of resistance to such transformation. Powerful forces — both local and global — are deeply invested in the status quo. Economic elites and NGOs, think tanks and media projects funded by Western donors often work to frame redistributive politics as illegitimate or reckless. These networks are not new, but they have grown increasingly bold as support for the ANC has declined.

In June 2023, the Brenthurst Foundation — funded by the Oppenheimer family — convened a conference in Gdansk, Poland. Branded as a summit to “promote democracy,” the conference issued a “Gdansk Declaration” widely read as an attempt to legitimise Western-backed opposition to redistributive politics in the global South.

The Democratic Alliance and the IFP were present, along with former Daily Maverick editor Branko Brkic, and representatives of Renamo (Mozambique) and Unita (Angola), both reactionary movements that were backed by the West to oppose national liberation movements. The event marked the open emergence of a transnational alliance aimed at neutralising any attempt to challenge elite power in the name of justice or equality.

It is a reminder that the struggle to realise the charter’s vision will not be won on moral terms alone. It will require effective political organisation, ideological clarity, and courage. The Freedom Charter was born of struggle. It must now be defended and renewed through struggle.

ISAAC SANEY points to the global stakes involved in defending the Cuban revolution against imperialism and calls for resistance

1943-2025: How one man’s unfinished work reveals the lethal lie of ‘colour-blind’ medicine

The shared path of the South African Communist Party and the ANC to the ballot box has found itself at a junction. SABINA PRICE reports

RONNIE KASRILS pays tribute to Ruth First, a fearless fighter against South African apartheid, in the centenary month of her birth