John Wojcik pays tribute to a black US activist who spent six decades at the forefront of struggles for voting rights, economic justice and peace – reshaping US politics and inspiring movements worldwide

This year’s march and swim in a reservoir in the Peak District will continue the fight for 'access for all' in a nation where 92 per cent of land remains inaccessible to the public, writes SHAILA SHOBNAM

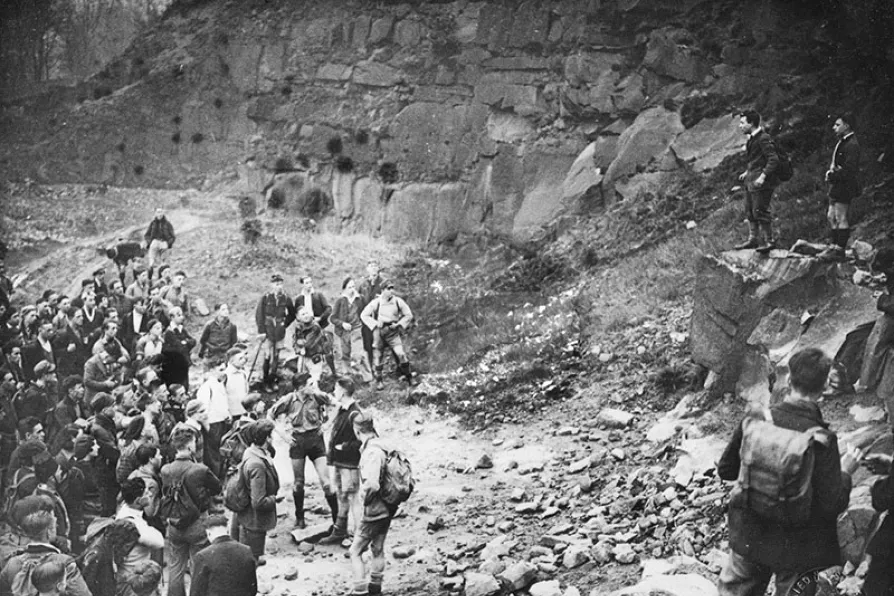

he famous trek up the Kinder Scout in Derbyshire in 1932

he famous trek up the Kinder Scout in Derbyshire in 1932

IF you have walked the rolling hills of the Peak District, a quiet debt is owed to the working-class youth of the Young Communist League (YCL). The quiet Derbyshire village of Hayfield, beneath Kinder Scout, stands as a symbol of the working class’s fight for land justice in Britain, where they challenged the elite and, against the odds, began to win.

From the 1600s onwards, England’s land was threatened by enclosure. In 1897, Hayfield residents, supported by the Peak and Northern Footpaths Society, won a legal battle to reopen the path, signalling resistance to private property-owner privilege.

Inspired by earlier acts like George Overstall’s imprisonment in 1873 and the Winter Hill Trespass, the 1932 Kinder Scout Trespass, led by the YCL and ramblers, marked a pivotal moment. Around 600 participants defied gamekeepers, linking land access to socialist struggle and crystallising the fight for public rights to land.

Today: still locked out

Nearly a century later, 92 per cent of land and 97 per cent of rivers in England remain inaccessible to the public. Private ownership, profit, and privilege still control access. Black, brown, disabled and working-class communities face exclusion through stigma, cost and discrimination. As part of a resurgent right to roam movement, the village is once again playing host to campaigners, walkers and agitators who believe in one simple truth: the land belongs to the people.

“Over half of England is owned by less than 1 per cent of its population, with around 30 per cent still in the hands of the aristocracy and 17 per cent with ‘undeclared’ ownership,” writes Guy Shrubsole in Who Owns England.

The key moment in land ownership today was the introduction of the Enclosure Acts (1604-1914). From then on, a new form of ownership, a form of privatisation, emerged. Enclosure involved the removal of common rights over farmlands and parish commons, leading to the reallocation of land from peasants into pasture enclosed by walls or fences, these landowners could close rights of way and forcibly evict residents. While some were given small, poorer-quality strips as compensation, laws protecting private property upheld this system.

Writing in the Tribune in 1944, George Orwell said: “Stop to consider how the so-called owners of the land got hold of it. They simply seized it by force, afterwards hiring lawyers to provide them with title deeds. In the case of the enclosure of the common lands … the land-grabbers did not even have the excuse of being foreign conquerors; they were quite frankly taking the heritage of their own countrymen, upon no sort of pretext except that they had the power to do so.”

Land, and who controls it, remains at the heart of many struggles for justice. As the moors echo with chants of “land for the people,” our thoughts extend beyond the hills of Derbyshire. The banners waving in the wind bear messages not only of local access and rights but of international solidarity — notably, Palestine and the Landless Workers Movement in South America.

This year’s march, like those before it, is not just an act of remembrance but a rallying cry for continued resistance against the privatisation of green spaces and the ongoing erosion of our access rights.

The struggle for justice — a global fight

We walk in honour of those who once broke the law to assert the right to walk freely on the land, and we also walk in grief and rage for those in Palestine who are being violently uprooted from theirs. In Gaza and the West Bank, thousands have been killed, displaced, and denied the right to exist, let alone roam.

The British state, which once locked up working-class youth for daring to set foot on private estates, now arms and assists a state that is actively engaged in ethnic cleansing. The struggle against land theft, apartheid, and colonial violence is not a distant one. As we climb higher, the symbolism deepens. It is a struggle rooted in our shared understanding: that justice means land back — not just here, but everywhere.

A shared struggle for liberation

From chants demanding “land for the people” to calls for climate justice and global liberation, this year’s Kinder Trespass march reaffirms our collective belief that the land belongs to those who live, work, and care for it — not the billionaires who fence it off, nor the landed gentry who abuse it.

To walk the path of those who came before us is to honour their courage and to carry forward the torch of resistance. As ever, the spirit of 1932 lives on in every step on the moor, every voice raised in protest, and every act of solidarity. It lives on in the call for land reform here and abroad, in the unity between working people, from Sheffield to Sheikh Jarrah. Let us not only remember the Kinder Trespass, but embody it — fighting for land, life, and liberation wherever they are under threat.

Will yo’ come o’ Sunday mornin’

For a walk o’er Winter Hill?

Ten thousand went last Sunday,

But there’s room for thousands still!

And the roads across the hilltops –

Are the people’s — yours and mine!

(Song written in 1896, Alan Clark)

Shaila Shobnam is a member of Birmingham YCL.

1943-2025: How one man’s unfinished work reveals the lethal lie of ‘colour-blind’ medicine

Remembering the 1787 Calton Weavers strike, MATT KERR argues that golden thread of our history needs weaving into the fabric of every community in the land

ANSELM ELDERGILL examines the legal case behind this weekend’s Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Festival and the lessons for today