The proxy war in Ukraine is heading to a denouement with the US and Russia dividing the spoils while the European powers stand bewildered by events they have been wilfully blind to, says KEVIN OVENDEN

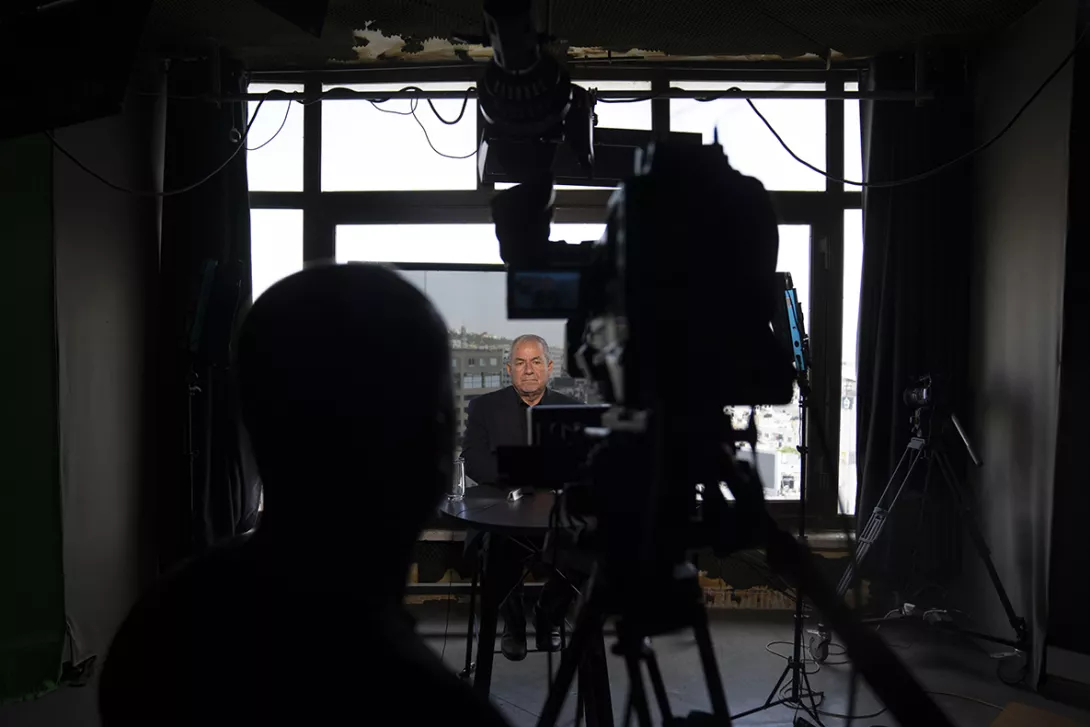

Israel is killing off Gaza's journalists – and it's evidently deliberate

The wholesale murder by Israel's armed forces of journalists in Gaza is a cause for international concern, writes TIM DAWSON

JOURNALIST Ismail al-Ghoul and cameraman Rami al-Rifi were adhering conflict-zone-reporting best practice as they drove from their assignment at the end of July.

Having documented issues facing the displaced of northern Gaza, they were departing the scene of greatest danger. They wore blast vests bearing the insignia PRESS and minutes earlier had updated the Al Jazeera newsroom with their location.

However, it was not enough to save their lives. An Israeli drone strike hit their car, with such an explosion that al-Ghoul’s head was blown off. Grisly images of his corpse were subsequently shared on social media. Al-Rifi, and Khalid Shawa, a boy who was passing on a bicycle, also died instantly.

More from this author

TIM DAWSON looks at how obsessive police surveillance of journalists undermines the very essence of democracy

At long last the WikiLeaks founder is free. For all those who care about freedom of speech it’s time to celebrate, writes TIM DAWSON of the International Federation of Journalists

There have been assurances that Assange does not face the death penalty, but no clear answer as to whether the US first amendment will apply to him; regardless, he should be released and returned to Australia, writes TIM DAWSON

Similar stories

One year on from October 7 2023, the general secretary of the International Federation of Journalists, ANTHONY BELLANGER, deplores the paralysis of the UN and denounces the international community’s lack of action

With bombing unending in Gaza and settlers rampaging in the West Bank, the ICC’s moves charge Israeli officials, though an important milestone, show no sign of changing the occupation’s genocidal course, writes VIJAY PRASHAD