IN 1967 the 14 largest steel companies were nationalised to become the British Steel Corporation (BSC). In 1979 I was shown the shape of things to come when in Wales BSC Shotton and Borth lost 7,000 jobs.

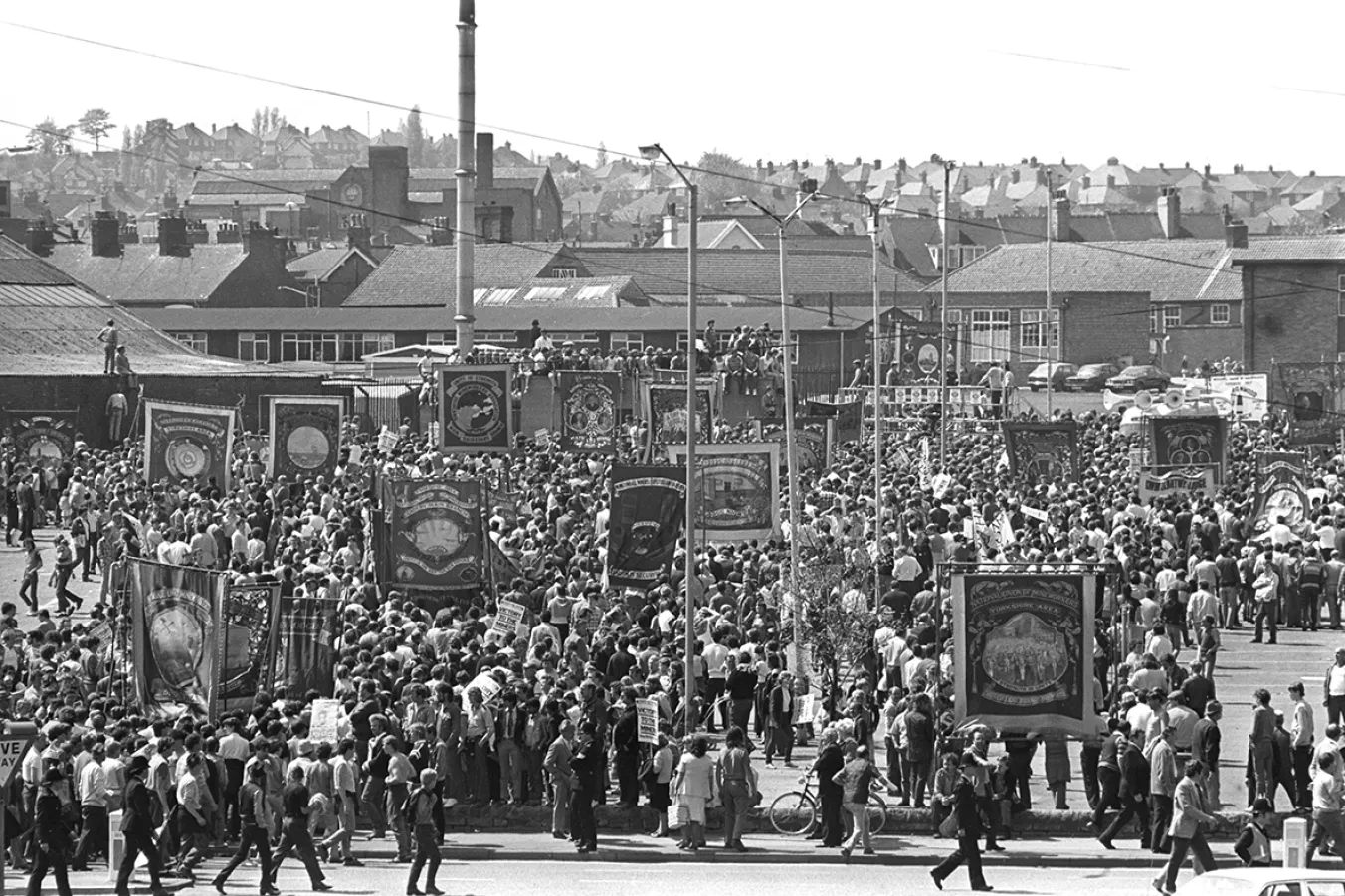

On January 2 1980, 100,000 steelworkers went on strike over pay — “the largest strike in post-war history,” lasting over three months and seen as a test of Margaret Thatcher’s attempts to curb wages and attack the nationalised industries.

Government papers showed it played a direct role in the strike’s conduct and as a test of their new monetarist doctrine. It was a strike in which the workers were starved back to work.

The steelworkers “won” a 1 per cent wage when seeking 20 per cent and returned to work in early April 1980, with the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation’s (ISTC) right-wing general secretary Bill Sirs declaring this a victory. Port Talbot and Llanwern lost 11,000 jobs shortly after the strike.

On August 21 1982 our front page lead chronicled the next chapter in the steel industry saga: “Yesterday, steel workers reacted with anger and determination to fight massive new redundancies in Sheffield and Scotland with closures and mergers meaning at least 1,600 job losses.”

“Scotland’s ISTC official Frank Lyons saying, ‘We intend to fight this to the bitter end.’ In Sheffield, Cliff Wright, convener at the River Don works, tells management that: ‘We will not accept and we will fight for every job,’ adding that, ‘With the jobs lost in the area there is nowhere to go. If we have to sit in we will sit in.’”

These kinds of words were heard up and down the country but no-one knew the extent industries were to be closed down by Tory policies hastening their end, industry after industry.

High energy costs and the failure to invest in new technology contributed to the crisis. Thatcher’s fixation with market forces allowed and encouraged the import of cheap foreign steel.

Thatcher’s political philosophy and economic policies emphasised deregulation, particularly of the financial sector, flexible labour markets, the privatisation of state-owned companies, and reducing the power and influence of trade unions.

Elected in May 1979 she was aided in this by her right-wing industry secretary Sir Keith Joseph, and it was he who appointed Sir Ian MacGregor chairman of BSC in 1980. He would be in the vanguard of the Thatcher government’s programme of privatisation.

That British government paid his then-employer Lazars a £1.8 million settlement. Britain’s workers in cars, steel and coal where he held pivotal posts were to pay a heavier price.

At BSC his four-year tenure result was carnage; made against a background of mounting unemployment it savaged the traditional steel-working communities. By 1983, this meant 166,000 staff had been sacked and BSC was making a loss of £1.8 billion annually.

On August 25 1982 the unemployed numbered 3,292,702 (13.8 per cent of the population) — a rise of 100,000 in a month. Vacancies were only 113,440, meaning 30 people chasing every job. Half a million young people were walking the streets.

In September I picked up a dispute where people in pursuit of justice for others brought about great change in the lives of some worse off than themselves at the Rowton House chain’s Arlington House hostel in Camden, London.

“Fifty-six sacked workers at Britain’s largest hostel for men on miserable wages, face eviction threats from grim living conditions that could have come straight from the pages of Charles Dickens.

“The staff at the 100-year-old 1,066-bed cubicle hostel share the same facilities as the residents in 7-foot by 5-foot rooms with a bed, chair, and small wall cupboard.