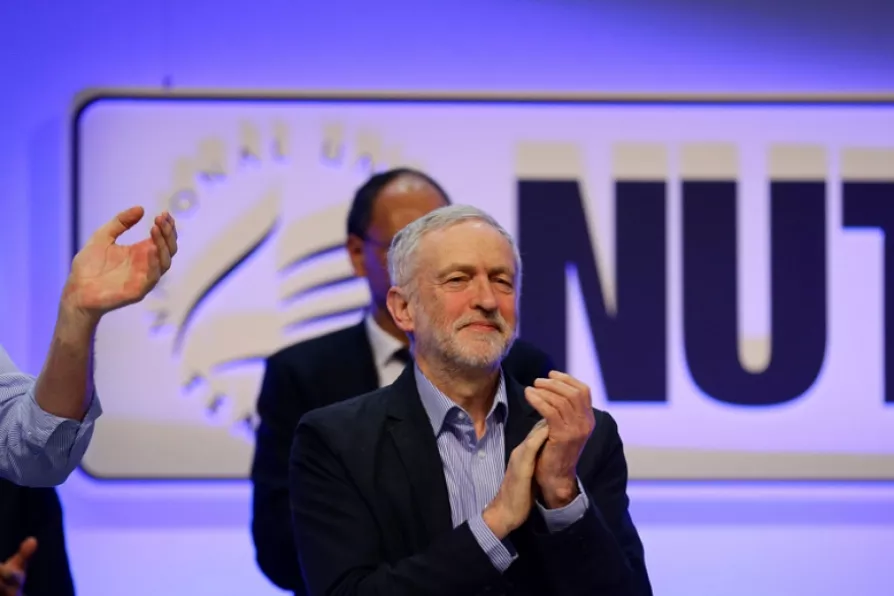

PROUD HISTORY: Joint NEU general secretary Kevin Courtney applauds Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn at 2016's NUT conference

PROUD HISTORY: Joint NEU general secretary Kevin Courtney applauds Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn at 2016's NUT conference

DELEGATES gathering for the last conference of the National Union of Teachers will have a number of chances to celebrate the extraordinary history of a union that has been centre stage in public life for all of 147 years.

They will receive a copy of a popular pictorial history entitled Pride, Passion, Professionalism: The NUT and the Struggle for Education 1870-2017.

Though written by author and activist Martin Cloake, this history draws on a collaboration between colleagues with a variety of skills. But then how could a history of the main teachers’ union not be based on working together?

Maggie Bowden was a trailblazing campaigning lawyer at Birnberg and Thompsons, women’s organiser of the Communist Party, and general secretary of Liberation

PHIL KATZ describes the unity of the home front and the war front in a People’s War

The devastating impact of austerity has left Scotland’s education system on its knees, argues ANDREA BRADLEY, urging politicians to show courage by increasing wealth taxation to fund our schools properly

We face austerity, privatisation, and toxic influence. But we are growing, and cannot be beaten