The proxy war in Ukraine is heading to a denouement with the US and Russia dividing the spoils while the European powers stand bewildered by events they have been wilfully blind to, says KEVIN OVENDEN

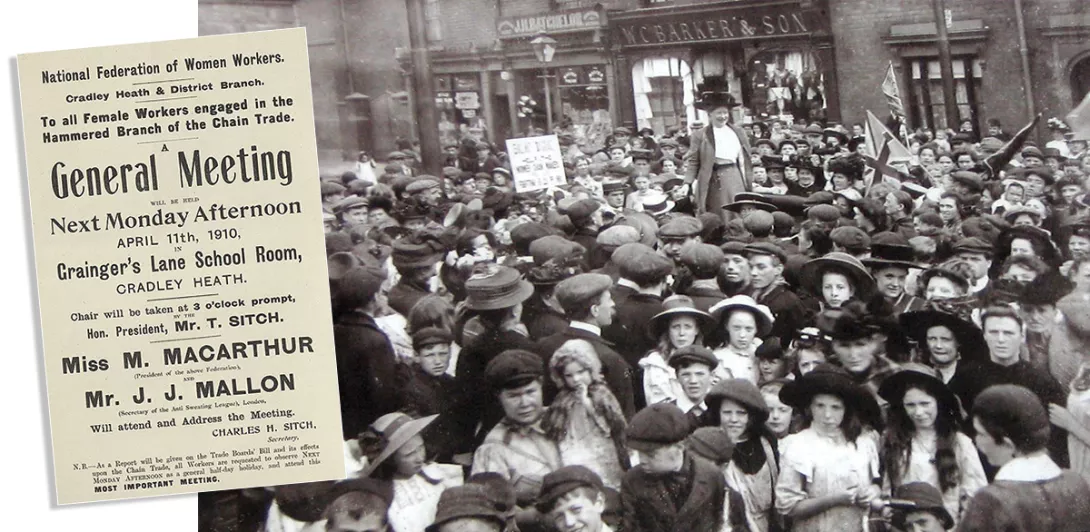

When female workers enforced Britain's first minimum wage

MAT COWARD recalls a time when imaginative employment of newsreels helped secure a memorable victory for an industrial action by the chainmakers

YOU might well be tempted to set up The National Anti-Sweating League after getting stuck in a tunnel on the rush-hour Northern Line, but a century ago “sweating” had a particular meaning.

In 1899, the House of Lords committee on sweating (look, I’m sorry, but if you're going to giggle every time, we'll be here forever) defined sweatshop labour by three criteria: it was underpaid, the hours were excessive, and the working conditions were unhealthy.

The point being that they meant bad pay, long days and crap conditions that were dramatically worse than the already dreadful norm.

More from this author

MAT COWARD battles wayward pigeons in pursuit of a crop of purple sprouting broccoli

Despite his wealthy background and membership of a secretive aristocratic occult club, the radical politician forged an alliance with the working class to fight for democracy and free speech against the Georgian elite, writes MAT COWARD

MAT COWARD offers a roll call of refuseniks – some for political reasons, others for quirky reasons of their own

Charles Dickens was facing a return to the destitution that had blighted his childhood, and it was this which drove him to write the remarkable best-seller which changed the politics of Christmas forever, writes MAT COWARD

Similar stories

From swimming pool soviets to piano factory occupations, early 20th-century radical organiser Lillian Thring chose street battles and mass action over the electoral path, writes MAT COWARD

MAT COWARD resurrects the radical spirit of early Labour’s overlooked matriarch, whose tireless activism and financial support laid the foundations for the party’s early success

MAT COWARD looks at how the bicycle helped spread socialist education and the holiday camp was invented for the benefit of the working class

MAT COWARD delves into the riots that saw ex-soldiers ransack a banquet, commandeer a piano and torch the town hall, enraged by tone-deaf officials’ elitist armistice celebrations