Hands of Stone

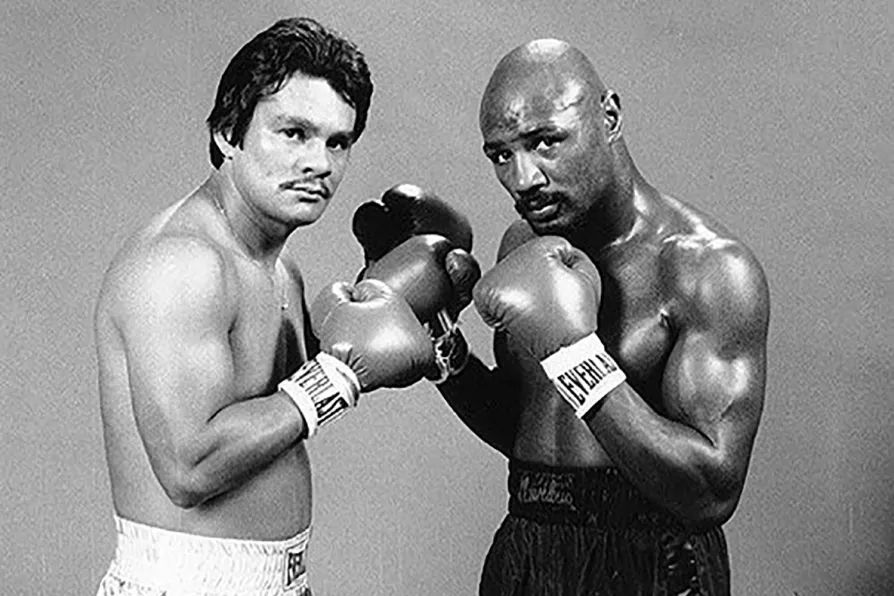

Roberto Duran and Marvin Hagler

[Creative Commons]

Roberto Duran and Marvin Hagler

[Creative Commons]

“I AM not God, but I am something similar.”

These words were once spoken by Panamanian legend Roberto Duran, whose ring name Hands of Stone captured the primal character of a man who faced nothing in the ring that ever came close to what he faced out of it.

Having just defeated his latest and perhaps most deadly opponent, Covid-19, Duran is a man for whom the label ATG (all-time great) most accurately applies — who even in his most humiliating moment — his “no mas” surrender to Sugar Ray Leonard in their 1976 rematch in New Orleans — retained an aura of dignity consonant with the struggle for survival and to escape the grinding poverty from whence he had come.

Similar stories

JOHN WIGHT writes about the fascinating folklore surrounding the place which has been home to some of the most ferocious bareknuckle and unlicensed fighters throughout history

JOHN WIGHT questions how legend of the sport Roberto Duran is lending credibility to the sportswashing circus that is Riyadh Season — and at what cost?

Following the untimely death of 28-year-old Irish boxer John Cooney, JOHN WIGHT explores how the sport can be made ‘safer’ than it is at present

JOHN WIGHT writes on legendary boxing trainer and philosopher, Cus D’Amato