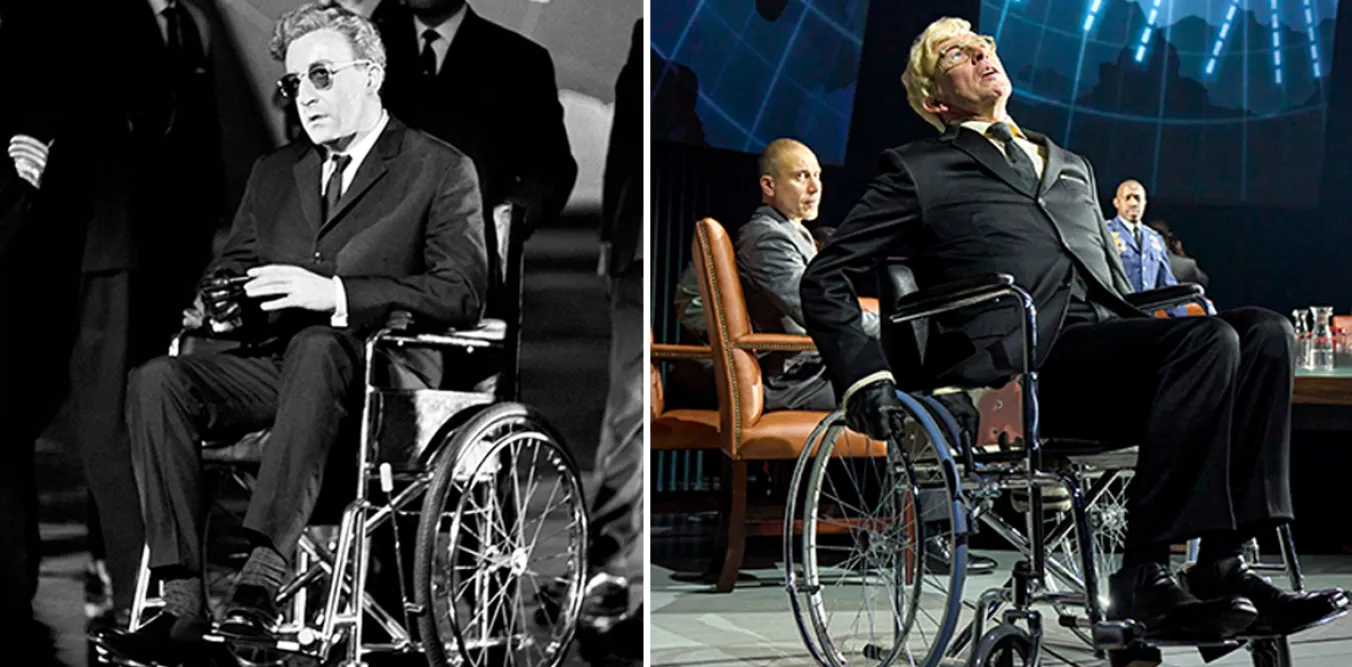

STANLEY KUBRICK made Dr Strangelove sixty years ago.

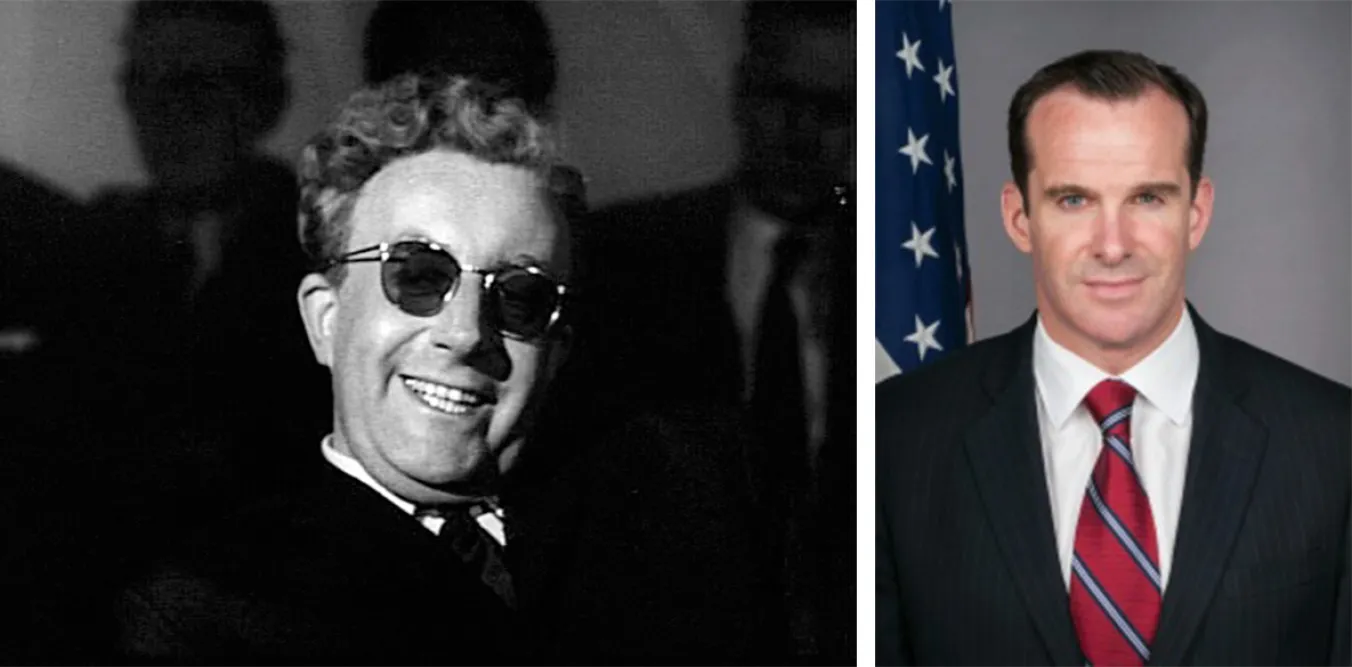

This black comedy is old enough to be filmed in black and white, but remains a compelling film because the characters seem to recur in real life: like Strangelove himself, the sinister adviser who pushes a horrible, heartless plan of war and death on a hapless president. Or General Ripper, the macho military man who goes a bit “funny in the head.” And, of course, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, representing the British, who flap about in a vague, posh way while being dragged along by US military adventures.

It’s fairly common for US presidents to have a “Strangelove” figure: many thought he was based on Henry Kissinger, who “Strangeloved” for successive presidents, although he was actually drawn from earlier characters including Cold War “intellectual” Herman Kahn.