RICHARD BURGON MP speaks to Ben Chacko about the Labour right’s complicity in the Mandelson scandal and the need for a total break with Starmerism if the party is to defeat Reform

When punk took on the prime minister: the story of On Resistance Street

When Boris Johnson claimed The Clash were one of his all-time favourite bands, a group of outraged real punk fans decided it was time to reassert punk’s radical, anti-racist, anti-fascist roots. LOUISE RAW explains

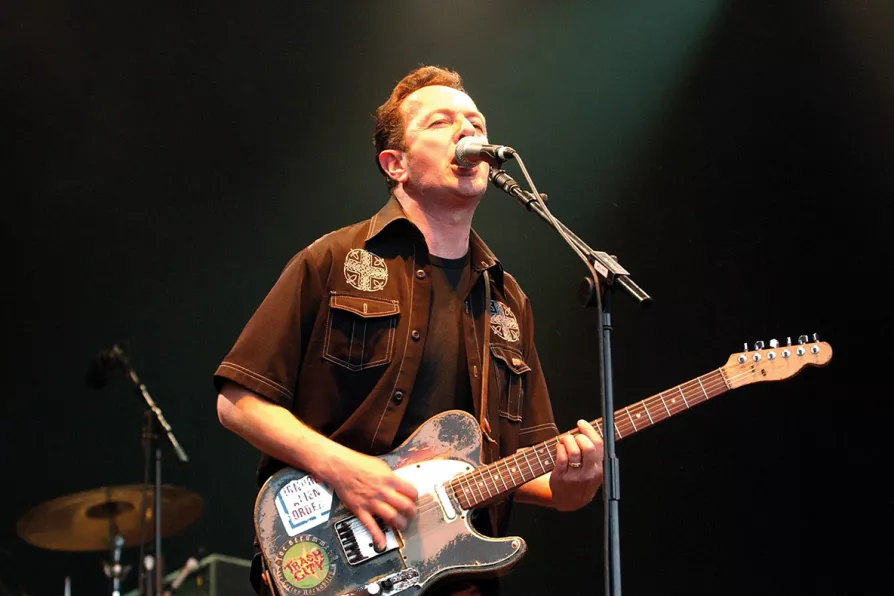

Joe Strummer and the Mescaleros performing live on stage at the Fleadh 2002 Music festival, Finsbury Park, North London

Joe Strummer and the Mescaleros performing live on stage at the Fleadh 2002 Music festival, Finsbury Park, North London

“Don’t pretend to like the Clash, you lying Tory fuckbrain!”: Clash fan to Boris Johnson (X).

Similar stories

DAVID HORSLEY reminds us of the roots and staying power of one of the most iconic festivals around

Fiery words from the Bard in Blackpool and Edinburgh, and Evidence Based Punk Rock from The Protest Family

RON JACOBS welcomes a survey of US punk in the era of Reagan, and sees the necessity for some of the same today

This year’s Bristol Radical History Festival focused on the persistent threats of racism, xenophobia and, of course, our radical collective resistance to it across Ireland and Britain, reports LYNNE WALSH