With speculation growing about a Labour leadership contest in 2026, only a decisive break with the current direction – on the economy, foreign policy and migrants – can avert disaster and offer a credible alternative, writes DIANE ABBOTT

What can we learn from the ‘Red Summer’ of 1919?

ROGER McKENZIE draws inspiration from the black self-organisation of the early 20th century

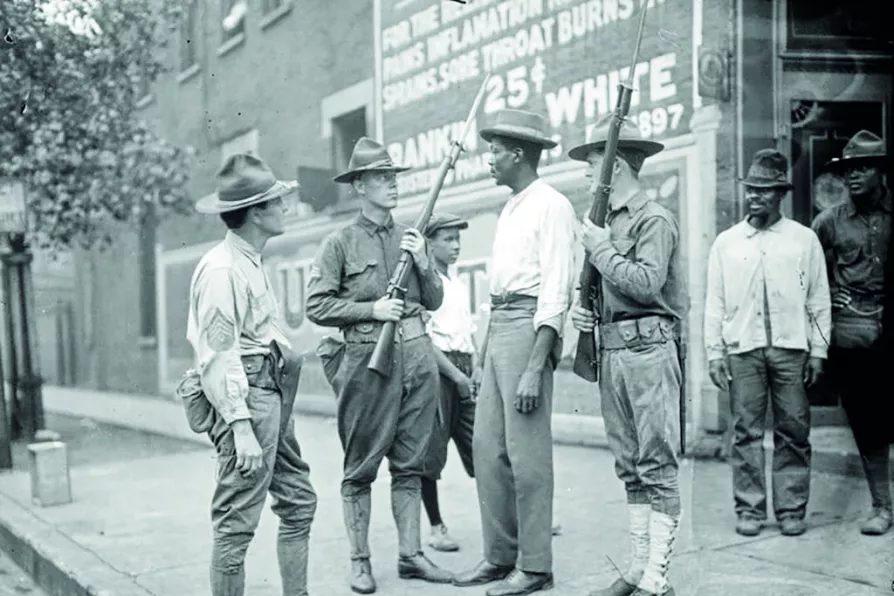

National Guards accost black men on the streets

during the ‘Red Summer’ disturbances, Chicago, Illinois, 1919

[Chicago History Museum / Public Domain]

National Guards accost black men on the streets

during the ‘Red Summer’ disturbances, Chicago, Illinois, 1919

[Chicago History Museum / Public Domain]

LIKE many people in the depths of the winter I have begun to look forward to the warm days of the summer.

But looking ahead this year I am reminded that it will be the 125th anniversary of the “Red Summer” of 1919.

The summer of that year was as red in Britain as it was on the other side of the Atlantic in the United States.

Similar stories

DAVID HORSLEY reminds us of the roots and staying power of one of the most iconic festivals around

White racist rioting has many an infamous precedent in Britain, writes DAVID HORSLEY

JOGINDER BAINS argues that the infamously cruel and calculated mass murder of Indians blocked into a public square and fired upon by the British Indian Army still faces a reckoning

ROGER McKENZIE reflects on the enslavement, endurance and rebellion of Africans trafficked across the Atlantic and the untold sufferings of unknown ancestors