GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

The twin roots of our discontent

ALEX HALL welcomes an accessible examination of the two strands of pro-capitalist thought which have defined the post-war economic policies of the West

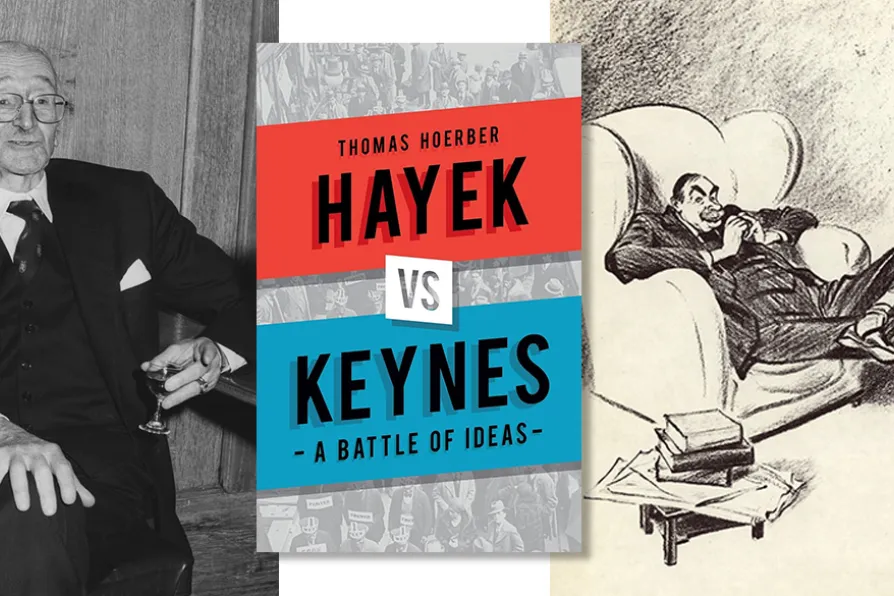

(L) Friedrich August von Hayek, 1981; (R) John Maynard Keynes, 1934

[LSE Library/CC; David Low/CC]

(L) Friedrich August von Hayek, 1981; (R) John Maynard Keynes, 1934

[LSE Library/CC; David Low/CC]

Hayek vs Keynes: A Battle of Ideas

Hoerber Thomas, Reaktion Books, £10.99

NEITHER John Maynard Keynes nor Friedrich von Hayek wanted to see the devastation of the Great Depression or the second world war again. Both understood how economics and politics could tear societies apart.

Both wanted societies which would encourage harmony and efficiency. But they came up with very different solutions, Keynes focusing on the role of government in creating the right environment for markets and controlling their worst excesses, and Hayek on the role of maximising individual freedom and free markets.

Similar stories

SETH SANDRONSKY savours a personal account of the life and thought of the great Italian revolutionary

ANDREW MURRAY casts an eye over past upheavals and asks whether the left can find a fire escape before the world goes up in flames

Labour’s fiscal policy is already in trouble. But simply printing money is not a solution, says the Marx Memorial Library and Workers School

STEVE ANDREW welcomes a political interrogation of the contradiction between ecological awareness and a dietary crisis in today’s food consumption